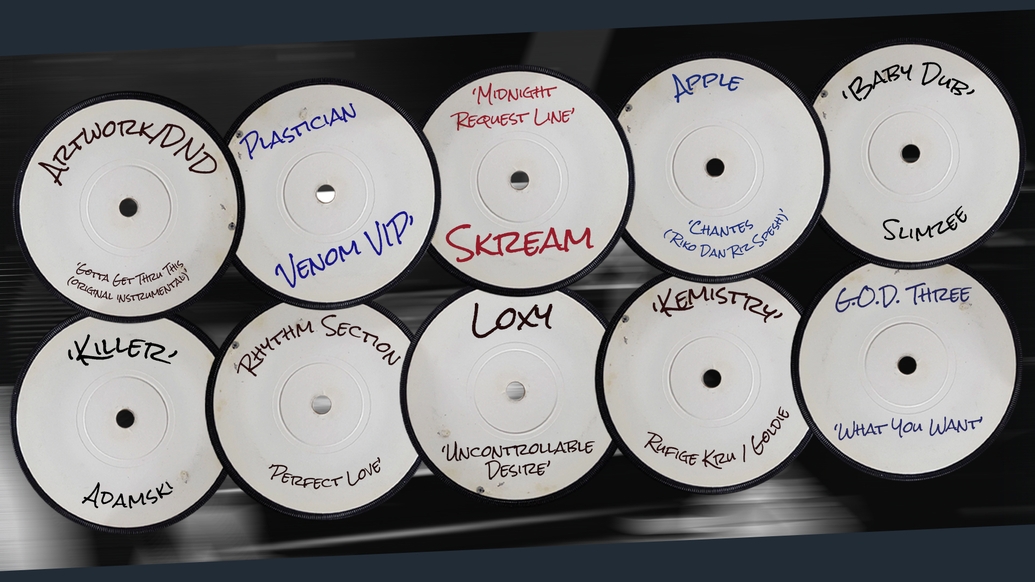

10 essential dubplates from UK dance music culture, picked by the DJs that play them

10 DJs select their most treasured dubplates, from the original versions of classic tracks to ultra rare cuts forever etched into just a handful of discs

This feature is part of our Record Store Day content series. You can also read our feature on the rise, fall and revival of UK dubplate culture, and also find out how to survive as a record store in 2023

“Dubplates were for road-testing tunes. If they didn’t do well, they never came out. The big tunes you had on dubplate that ended up being classics, they’ve all got a mini story. I’ve got Adamski ‘Killer’ on dubplate. I think it was the first dub I ever got. I knew Adamski’s girlfriend really well. He was just blowing up and was doing this live thing nobody had seen before. He was a big fan of mine and I was a big fan of his, we had this mutual respect. One day he said, ‘I’m going to make you a real Fabio tune’. Later his girlfriend told me it’s the best thing he’s ever done. I heard it on a cassette and it was ‘Killer’. I asked how I could get a copy and she said, ‘Adam’s going down to the master press, he’s going to cut a dub’. So he cut ‘Killer’, I think at JTS, with two versions that never came out. When he gave it to me it was like getting a gold disc. Two or three months later it was at number one. And now [vocalist] Seal’s a multimillionaire, having children with Heidi Klum and living in Calabasas next to Kim Kardashian!”

Only one dubplate of this was ever pressed, and belonged to Ellis Dee. You can hear it played in his Dreamscape 2 mix from above 1992 above

“Rhythm Section did a track called ‘Perfect Love’. At the time, I was DJing about three times on a Friday and four on a Saturday. We’d make the tunes, I’d get them cut on a Friday, then play them and suss out which bits were good and which bits weren’t. We’d go in the next week, fix it up and try it again the next weekend. That would determine which version we’d release. It wasn’t much of a thing playing other people’s dubplates, not like it was with jungle and drum & bass. We’d go to JTS in Hackney, which was originally a reggae sound called Jah Tubby’s Sound. It used to be on Broadway Market before it was trendy. You’d go round the back of this house, walk through a garden that was full of old engines and go up these rickety stairs. How they got the lathe up there, I do not know. As time went on he had a place over in Homerton with a few more cutting rooms. A much plusher affair. The process didn’t work with ‘Perfect Love’ because it turned out everyone wanted the original dubplate version. By the time we realised that, the DAT had gone and none of us could find the dubplate. So the version we released, although it was good, wasn’t as good as the dubplate version. We only found out afterwards.”

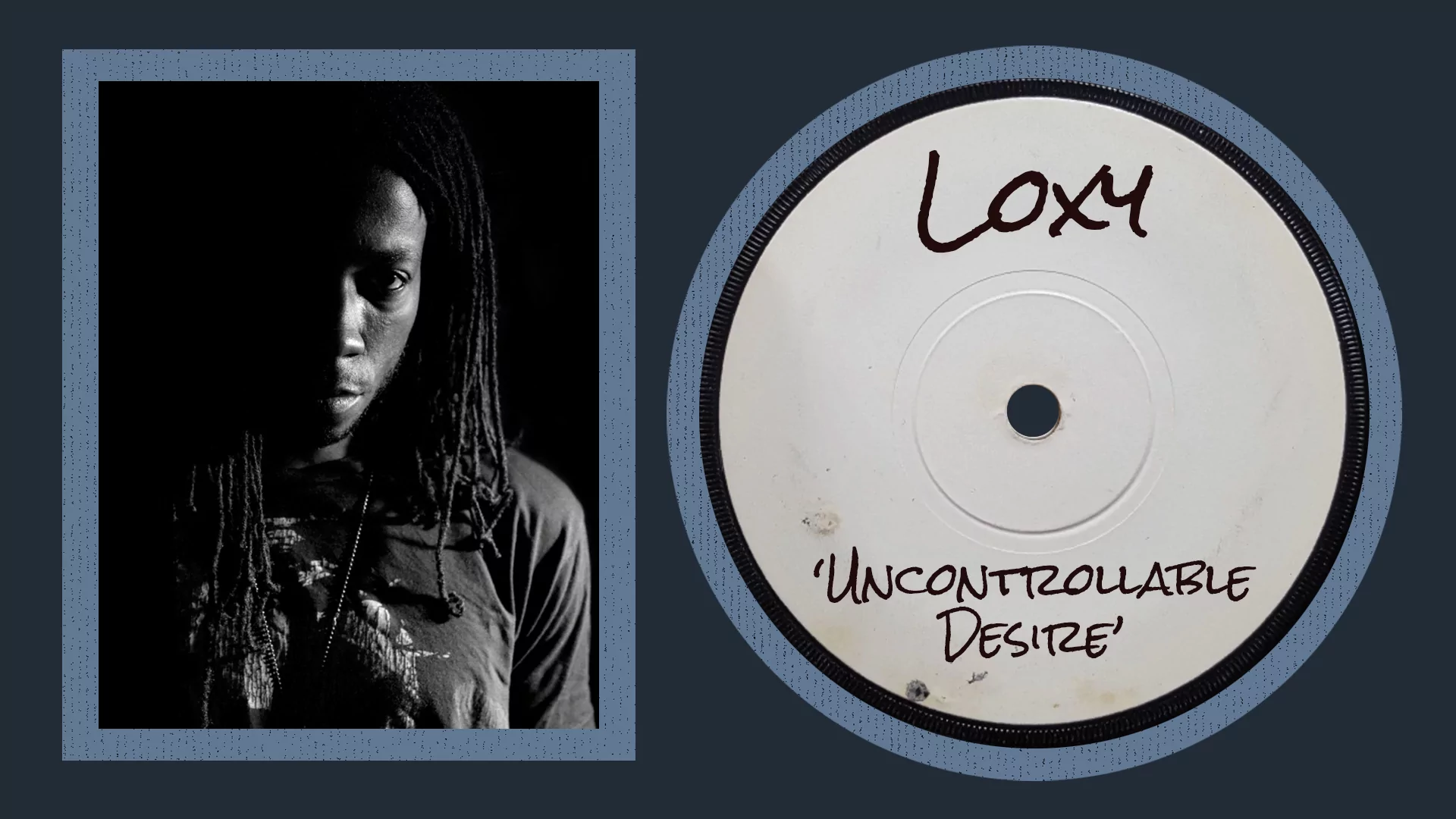

“I went to Telepathy at Marshgate Lane in 1990. After that I decided I wanted to DJ and started getting gigs. But a few years in people tell you doing tunes will set you apart. That was my motivation, having my own stuff to play. Reinforced was the main inspiration. Without that, there is no me. I found out about Music House via other producers. As soon as I went there, I built a rapport with Chris and Paul who ran it at the time. They’re just funny guys. You go there to cut but it’s also a social thing. The first three people I sorted out with ‘Uncontrollable Desire’, my first track, were DJ Rap, Bryan Gee and DJ Trace. Playing your own track for the first time is monumental, a eureka moment that I can do this. No U-Turn wanted to sign it. Nico called me, so I went to the studio and met Ed Rush and Optical. It was pivotal because I formed a relationship with those guys. The tune gets a bit crazy in one section. Bizzy B [whose studio it was engineered in], back then their whole thing was really edited amens. Nico wanted me to smooth it out but trying to book time to get back into the studio, it just became a long thing. So Nico said, ‘Let’s do something at a later date’. But I’d already built connections. Without that, I might not be where I am now. The funny thing is, Equinox still wants to release it. He told me, ‘If you find the DAT I’ll put it out as a lost dub’. So there is the possibility it could still come out.”

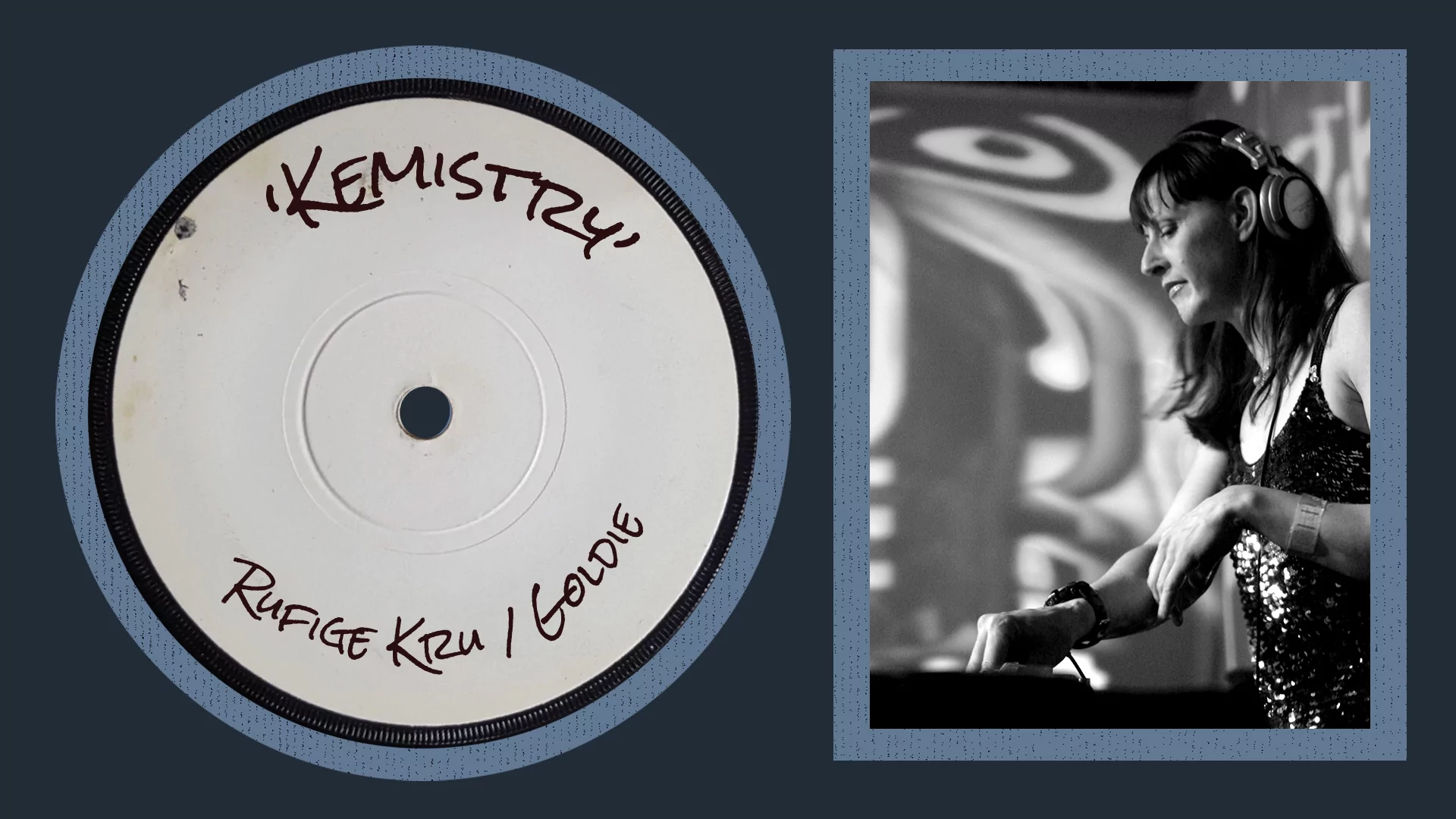

“Goldie made it for Kemi [the other half of Kemistry & Storm], so it always had significance. I think it keeps her memory alive and she was probably the first person to play it. She was never that keen on the vocal. Goldie brought it home really excited, then Kemi was like, ‘The vocal’s a bit...’, which crushed him a little. So he made the instrumental version. The two came out at the same time, but we had them both on dubplate for a long time. You had a few remixes, too. It was probably the most amount of dubplates we had of one tune. I think the last one was the Doc Scott remix, which was around the first time Goldie managed to get into Heaven. That was our religion, going to Rage on a Thursday. He decided with London Records behind him and his first tour he’d be able to get in. It was also the first time Kemistry & Storm were playing alongside Fabio & Grooverider. The remix was rolled out that night and it tied together our career: going to Rage, meeting Goldie, taking him there. Wherever we went in the world, people came up to Kemi and [said], ‘I love that tune ‘Kemistry’ you made’. And Kemi used to say, ‘Cool’. In the beginning she’d explain about Goldie and Rufige Kru, but it became too long. People still come up to me to say, ‘I love that tune you made, ‘Kemistry’.’ And I say, ‘Thank you very much!’”

“When speed garage began to develop, it was really experimental for me. I was dipping into it and trying to work it out. I had a jungle background, so my early productions were leaning in that direction anyway. At that time, I’d hooked up with Karl Brown from Tuff Jam and was starting to go with him to get dubplates cut. This particular track I made on a Thursday night. The following Friday morning I met Karl Brown at JTS with our old mate Freddy Freshplate. We got it cut and he played it the same evening. For me that was gold, because it enabled me to see what actually worked on the dancefloor, sounds-and arrangement-wise. It went down a storm. At the time Karl Brown was DJing everywhere, He was doing three or four venues on the same night, so I think we went to the Gass Club, Cookies & Cream and Twice As Nice. Seeing the reaction in all these places, I was like, ‘Wow!’ People were hearing it for the first time as well. It was good for me, but it was good for Karl as well. He got tracks that nobody else had. He’d cut the dubplate but didn’t write my name on it in case anybody looked over. He didn’t tell anyone it was me. But it helped me hone my engineering, checking if the bass was too loud or the vocals too low. I could tweak it back in the studio. The reaction to that track made us confident it was ready to be released.”

“We started Sidewinder in 2001. So I got all these tunes that were big at the time and made a special dub filled with garage and grime tracks. Every eight bars it changes, with a vocal that says ‘Baby’ in between. It’s an iconic dubplate that Dizzee and Wiley spat on. Back then I was setting up pirate radio every night and meeting people, talking to producers and MCs like Jon E Cash. I was helping a lot of people come through, such as Agent X and Musical Mob who made ‘Pulse X’. Even though I was doing radio every night, we’d get special dubs for Sidewinder. That was the best rave. We made special VIPs just to hear there. I’d go to Music House. I went there for years, as I was a jungle DJ before garage and grime. I couldn’t really break through that scene, so I started playing slowed-down drum & bass, like a Mampi Swift tune called ‘Jaws’, alongside garage for MCs to spit on. Dizzee Rascal’s studio was in Bermondsey, which was also the studio of Cage, Dizzee’s manager. Cage engineered the dubplate. We sampled each track and added a 20-second intro. The first track was DJ Narrows ‘Saved Soul’, then the next one was More Fire Crew. It was the best bits from every tune, four or five minutes of pure energy. I remember the first time I played it, I thought, ‘I better hype things up’; I dropped the dubplate and it went mad.”

“Daniel Bedingfield’s ‘Gotta Get Thru This’ was running for roundabout a year as a dub on the club circuit. It became so popular, I think that’s why they started fishing for a singer. Everyone close to Arthur [aka Artwork, one of DND] had access to the plate. He was part of Tempa Records, which was a label and crew putting out tracks. It was run by Sarah Lockhart, who also used to own and run Rinse FM. This label, I’d call it the first dubstep label, but the phrase dubstep wasn’t even coined at this time. So she had the first label, and the first club night, which was FWD>>, which gave birth to the dubstep scene. In the early days, you’d see the same crew down there: Oris Jay, J Da Flex, Benny Ill, Zinc, Plastician, me and all the rest of them. That was one of the places you’d bang this dub. It was the only track that sounded like that. Even though it’s quite a commercial backing track, it had this kind of groove that was fat and bassy. DJs were playing it in FWD>> as a kind of signature, fluffy track. As soon as it did get signed and got to No.1, we had the celebratory party for it in FWD>>. Then it did No.1 in America. Natasha Bedingfield was actually originally going to sing, but couldn’t for some reason. They came across Daniel through her.”

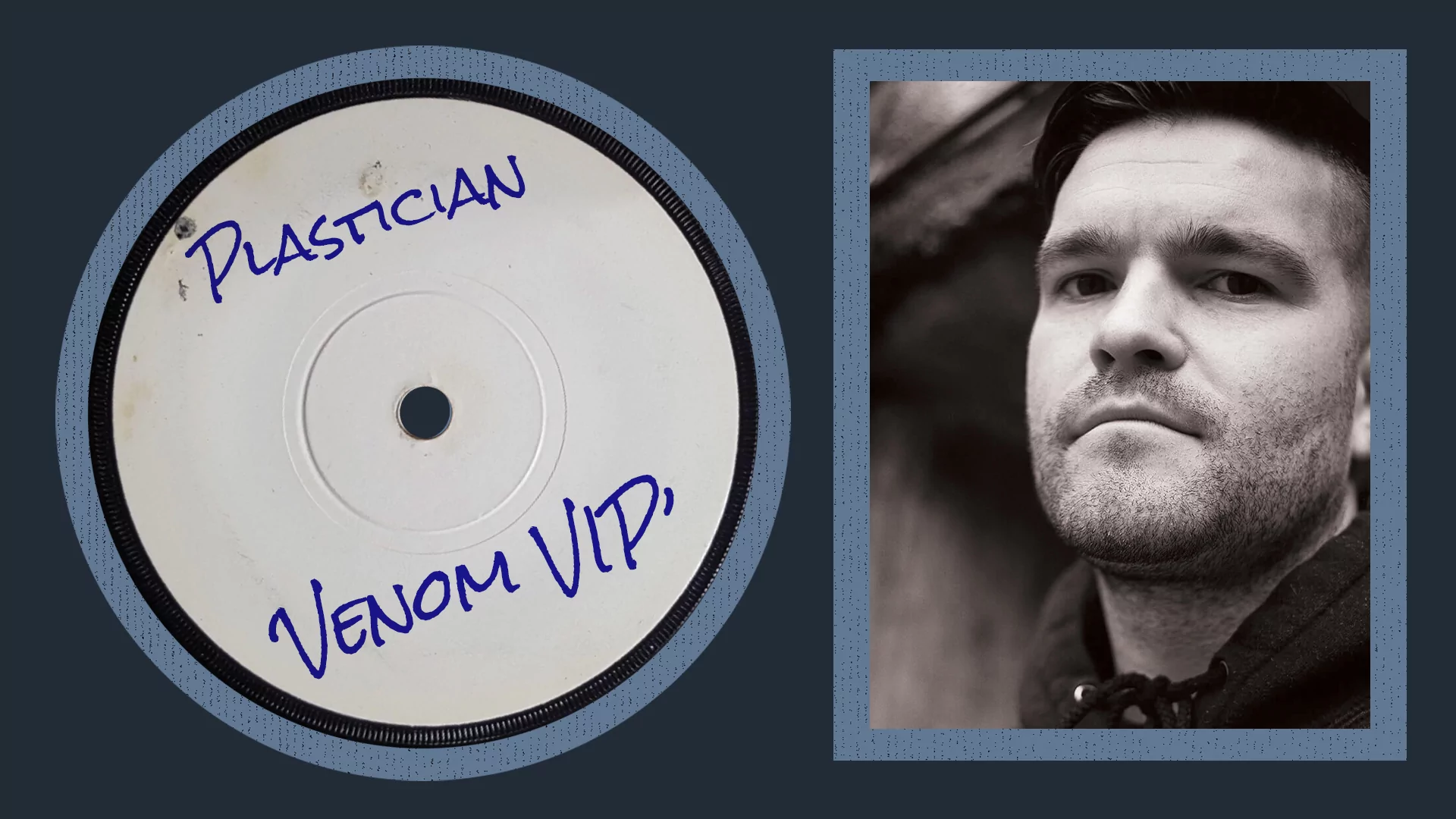

“The first time I met Skepta was at Music House cutting a VIP of my track ‘Venom’. The original, a popular instrumental with grime DJs, was out on Slimzee’s Slimzos Recordings. I used Transition in Forest Hill quite a bit, because it’s closer to where I lived. But occasionally I’d go to Music House because I knew people from the grime circuit cut dubplates there. You’d meet other DJs and producers. As someone who wanted to play the newest music, it was a way of getting beats for my sets and radio shows. While I was cutting, I think with Leon, God rest his soul, someone burst through the door. ‘Did you make this tune?’ I said, ‘Yeah’. So he asked if he could get an exclusive of it and gave me his number. I spoke to him outside and he told me he was a producer whose name was Skepta. I knew who he was, he had a track called ‘DTI’ at the time that was quite popular. A week later I was working with my dad on a building site and a number I didn’t recognise rang. I answered it and Skepta was on the other end: ‘You done that dubplate yet?’ I told him I hadn’t had a minute. ‘Call me when you’ve done it,’ he said, then hung up. I thought, that’s the rudest guy ever. I don’t think I ended up even doing it. Fast forward a few months though, I’d got to know his brother JME through MSN Messenger. Then me and Skepta became really good friends. We’ve worked on a lot of music together over the years and are still good mates. But the first time I met him, the impression wasn’t great!”

“‘Request Line’ is an anthem with a lot of history and one of my all-time favourites. I was one of the first DJs to play it and instantly signed it to Tempa Records. Oli [Skream] was making music specifically for me. He understood exactly what I wanted: minimal, dark and deep. I think ‘Request Line’ is a dubstep hybrid and crossed over into the grime, garage and techno scenes. I got two dubplates cut of ‘Request Line’ because I knew one plate wasn’t gonna last long and I wanted to beat-juggle it, which was inspired by turntablists. I did it in a very simple/basic manner, but it worked perfectly. FWD>> at Plastic People was the first place I played the ‘Request Line’ dubplates, which was the best place to test new music and ideas because of the huge, amazing sound system and small, dark room. Plastic People was definitely one of my favourite clubs/venues in the world and I miss playing dubplates there.”

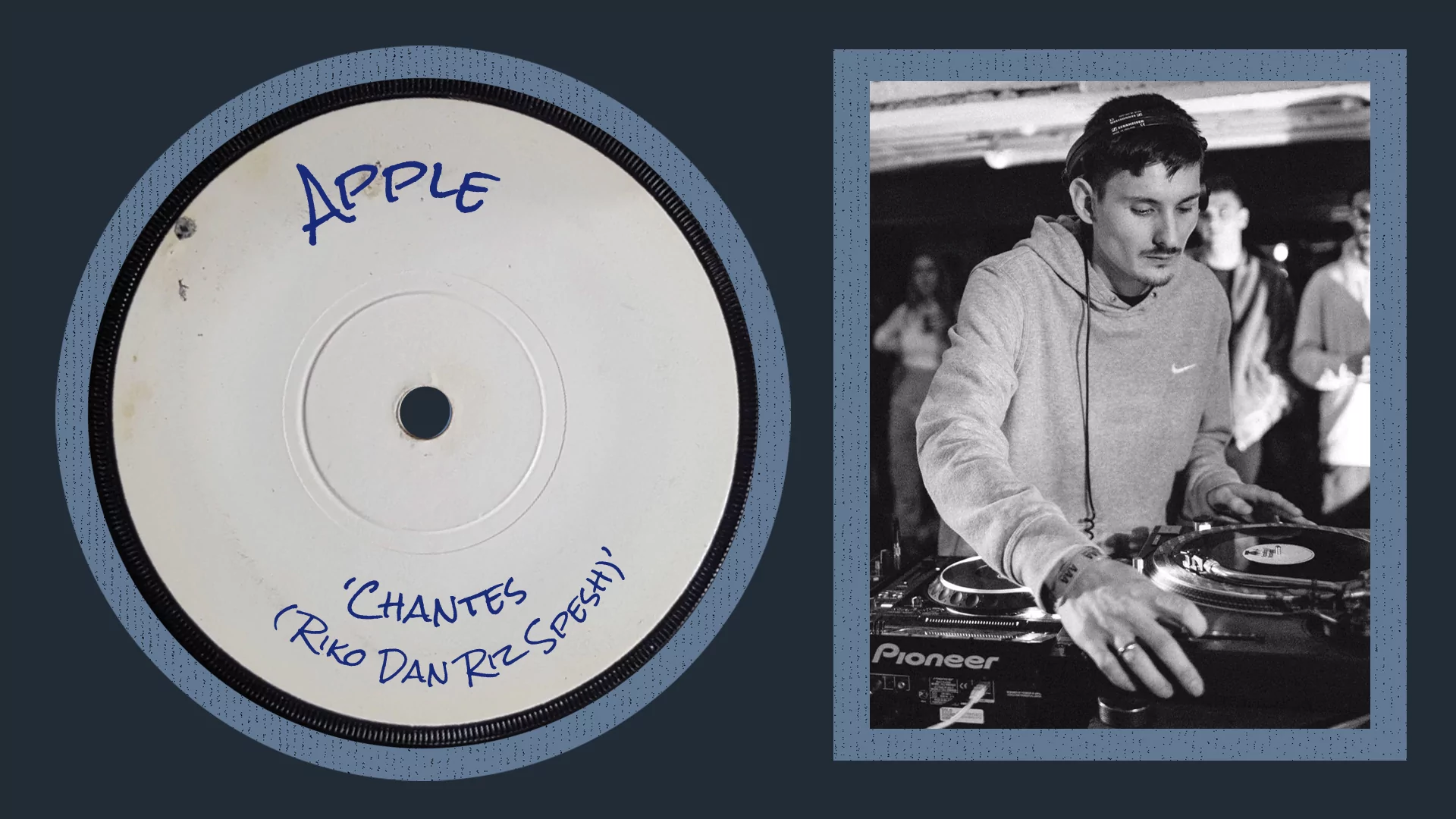

“When I was younger, everyone was playing dubplates: Skream, Mala, N-Type, Coki. I was real green, I didn’t even know what they were. I saw the Transition label and thought it was a record label. When I found out, I thought it was sick having your own tunes on acetate. My first experience was going to Transition and sitting with Jason. He walked me through how he was cutting. You go into this room with a massive unit of equipment and there’s a big German lathe. I used to cut with Music House, too, so I knew Leon. He’d cut me eight dubplates, then drive to meet me in Lewisham McDonald’s carpark, sometimes at 1 or 2 in the morning. I lived in Sutton at the time, miles away from Tottenham, so he’d meet me halfway. He’d pull up in his Beamer, hand me the dubplates, I’d hand him the cash, then he’d drive off. I still can’t believe he did that, he was such a nice guy. The idea for this dubplate came when I was playing after Mumdance in Brighton and Riko stayed on the mic while I crept up and started playing an old funky tune. He just went over the top of it and made me pull it. I wanted to get him on it as he’d never been on a funky tune before. Even now when I play it, people love it. It’s got my name in, so it’s a proper dubplate special. I’ve got others from AJ Tracey, Flowdan... a few more.”