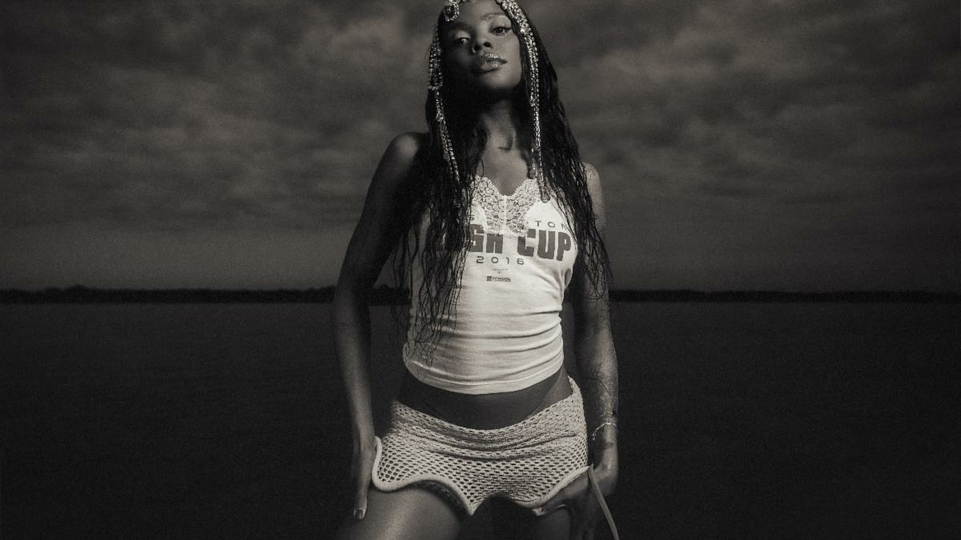

Aluna: age of enlightenment

Aluna Francis’s life has been one of discovery — of uncovering truths about herself, about society, and about the fundamental ways in which the dance music industry fails people. The Wales-born, LA-based music maker, formerly of AlunaGeorge and now working as a solo artist, tells Bruce Tantum how she’s putting the knowledge she’s gained into practice via the new Noir Fever festival

"I perhaps could have been a bit more cautious,” Aluna Francis — sitting in her downtown LA home, sunglasses perched upon her braided blue coif — says. “Maybe I could have said, ‘Well, you know, we can be mostly Black. Maybe we can have someone like Tiësto, and then everyone else be Black.’” She’s recalling an early meeting, with the promotional organisation Pollen, on the subject of Noir Fever, a three-day, multi-venue festival debuting in New Orleans on 27th May. She could have hedged her bets, but that’s not how Francis — one half of the popular alt-R&B duo AlunaGeorge and, more recently, a full-time solo artist — does things nowadays.

“When the opportunity to curate a festival came up, I made the decision to be completely transparent about where I was at,” she says. “In the very first meeting, I was like, ‘Look, there’s no point in me curating one of your festivals unless it’s really about what I’m about — and so this festival is going to be a Black festival, with an all-Black lineup. I thought that was gonna be the end of the conversation; I hadn’t even thought that they would entertain the idea. But because I laid it out like that at the very beginning, they went for it.”

A self-described “Black and queer, community-centered, three-day experience” complete with panels, speakers and workshops, Noir Fever’s lineup reads like a partial timeline of electronic music’s Black history. The old guard is represented with veterans like techno patriarch Kevin Saunderson and Chicago house champion Derrick Carter; the new schoolers, too, via artists such as Toronto’s genre-agnostic Bambii and the Nigeria-based alté activist Prettyboy D-O; and there’s plenty of room for the wide-ranging likes of Channel Tres, Jayda G, and Kaytranada.

As it happens, three of the fest’s big names — Saunderson, UNIIQU3, and TYGAPAW — have all graced recent DJ Mag covers. Francis, of course, makes the fourth, which makes for an odds-defying coincidence.

“Is it coincidence,” she asks, “or is there a pattern forming? I think what I’m doing is tapping into what is happening. I’m always surprised when it turns out that I was not the only one thinking about something, but that I’m just thinking about it early. Like, it turns out I’m not the only one who thinks that something is a good idea, you know what I mean?”

“I can only describe my formative years as living like a shadow. But shadows have lives, too — they can do all kinds of things"

Francis, a multi-hyphenate talent — she sings, writes, produces, and DJs, among other skills — is obviously not the first to ponder Black representation in a festival setting: There’s Brooklyn’s Dweller fest, for instance, and Afropunk has certainly had its club-friendly moments. But with Noir Fever, Francis is doing something about it on a grander and more complete scale than most. It’s an effort that’s borne of necessity — a need spurred in equal parts by her youth, her years spent in the mainstream end of the electronic music world, and her more recent education on the Black roots of dance music culture. It’s the result of a lifetime of learning experiences.

Francis had a nomadic upbringing. She was born in Wales, before moving to London with her single mother. Then there was a two-and-a-half-year stint in New Jersey, then a return to London, and then a few more moves around Hertfordshire in the UK's south east. “Those moves happened because we didn’t really have anywhere, so everywhere we went was kind of temporary,” Francis says.

“We lived in a school; we lived in a mobile home; we lived in a council house on a council estate. But I feel like my mom was always plotting, because the next move was always somehow better than the previous one. She’s a single parent, but she wouldn’t settle. She would always be like, ‘Okay, what’s better than here?’” They finally settled in St. Albans, an old cathedral town in Hertfordshire about an hour’s drive from London. “And I was the only Black person there.” Francis doesn’t go into details regarding the specific hardships that the situation presented, but those difficulties obviously left a mark.

“Being the only Black child in a white environment exposed me very, very clearly to the concept of otherness and the undercurrent residues of racism,” Francis says. “For me, it’s fundamentally about having been dehumanised, which leaves you in a very, very, very different position to everyone else around you. So I inherited, through my skin color, this idea that I was absolutely at no point ever worthy, or good enough, or that I belonged anywhere.

“There is no way for a single Black person to occupy space in an entirely white space,” she adds, getting a bit emotional. “I tried to as best I could, but it just left me on the edge of the direction that includes things like depression and self-harm. I can only describe my formative years as living like a shadow. But shadows have lives, too — they can do all kinds of things.” One of those things, of course, is music — which for Francis, served as a coping strategy as much as anything else.

“I had my little voice; I still have my little voice,” she laughs. “At age six, I had a tape recorder and would record songs, like ‘roses are red, violets are blue’ and then whatever rhymes you can add to that. I wrote a song on the guitar when I was eight — it was crap, but sweet. I sang in the choir, I sang in school plays. It was the only thing that I did where it came naturally.”

Life is full of intersections — and the choice of which direction to travel, and the vistas you’ll see along that path, can have a profound effect. Francis’s loomed in a supermarket parking lot. She was looking for a job, and her mother had driven her to the store for an interview.

“We were in the carpark,” Francis recalls, “and my mom innocently asked, ‘Do you actually want to work at the supermarket?’ I was like, ‘No, Mom, I just need a job.’ She asked, ‘Well, what do you want to do?’ And in a moment of madness, I said, ‘I want to be a singer.’ She was like, ‘Okay, well then you better just go and do that then.’” Just like that, Francis’s path was set.

The first step was singing lessons “working with an opera singer,” she says. “Then I was like, ‘right, I need to make some music. I need to join some bands.’” But she had little idea how to actually make that happen. “I went to an all-girls school, where the closest thing to a band was if you had a scratch and you put a bandaid on,” Francis jokes.

“But now I had to be online in chat rooms, and I had to meet guys in pubs, and I had to go to music rehearsal studios and look at the noticeboards to see if somebody wanted a singer, and I had to call them up and say, ‘Hello!’ Then I would go by myself to some guy’s house, wherever they were, knock on the door, and be like, ‘Okay, time to make music.’” Francis was in several bands before finding success with AlunaGeorge. First up: Earth Leakage Trip, a DIY-style garage band.

“It was psychedelic Pink Floydy stuff, in someone’s garden where they were growing weed,” she says. “They had this bong thing called a Volcano, and we’d get completely blasted, and then I would just sing the wackiest shit ever. And they would always be like, ‘Oh, wow, that’s so cool, that’s amazing.’ I’d ask, ‘Do you have any notes?’ And there’d be no notes. But as soon as someone’s happy with what I’m doing, I’m like, ‘okay, I’ve got to move past this’ — and I’d move on to the next one.”

Next was a duo called The Boundary. “It was me and this guy, both on guitar writing guitar songs, very shouty indie-rock music.” Francis wanted to test the music in a live setting, her partner wanted to wait till an album was out, though no such album yet existed. “I told him, ‘You know, we are nobodies — and no one is going to hear this album,’” she says. “‘We have to perform in whatever bar we can find.’ But he was having none of it, so I left that one.”

“I was starting to discover what was unique about my voice — the meaning of imperfections and finding out what’s uniquely you, instead of singing like some other singer that you’ve heard"

During this exploratory period, Francis lived for a time in squats, and worked a series of what she describes as “amusingly weird” side hustles to make ends meet. There was time spent as a children’s fashion show coordinator, a tiler’s assistant, a market trader, an on screen extra, and something called a “bar massage therapist.” “Like you have a beer, and I massage your shoulders,” as she describes it.

Her final pre-AlunaGeorge outing, formed in the mid ’00s — “the dawn of the electronic phase of my studies,” as Francis describes it — was in a band called My Toys Like Me with a producer named Gus Fernald, aka Lazlo Legezer.

“He was an old-school raver, and he had a whole heap of cool hardware, with the patch bays and everything,” she explains. “Our methodology was like, he’d come up with some wonky weird shit, and then just lock me in the vocal booth for 20 minutes to randomly come up with things. Then he would send me home. He would find moments where, in my mind, I’d made an accidental mistake, and then he’d play all that to me the following day.”

The results were another of Francis’s learning experiences. “I was starting to discover what was unique about my voice — the meaning of imperfections and finding out what’s uniquely you, instead of singing like some other singer that you’ve heard,” she says. “I would then write the lyrics to those little tiny snippets of my voice. It was all very alternative, avant-garde stuff.” The outfit had some success, performing live and releasing a pair of albums. It also led to Francis meeting George Reid, her soon-to-be partner in AlunaGeorge.

“My Toys Like Me had a song called ‘Sick Couple’ — if you want to hear how much I sound like Billie Eilish, go listen to that,” she jokes. The song made it to the late-night rotation on BBC Radio 1 — Reid heard the track and asked to do a remix. “And it was really good!” Fernald became enamoured of Reid’s studio skills.

“Gus had been talking about this guy, like, ‘He’s such a cool producer, he’s amazing,’ and finally he arranged to meet George,” Francis says. “I was like, ‘Alright, you guys go geek out.’” But, as it happens, the meeting didn’t go quite as planned. “I get a text from Gus: ‘You’ve got to come and meet us. Please!’ ‘Why?’ ‘It’s just really awkward. I don’t know what to say to this guy.’ So I got to the cafe and then I see immediately what’s happening: George is a young, beautiful teenager using Logic, not some veteran genius on patch bays. Gus was much older, well into his 40s, and he was crestfallen. So Gus was like, ‘Oh, look, here’s Aluna. You know what, instead of me and you working together, Aluna, why don’t you go and work with George?’”

The original idea was for Francis and Reid to write together, and then Fernald would step in as producer — but things didn’t go exactly as planned.

“I got to George’s house, and over a nice cup of tea sitting on the edge of his bed, we made a banger,” she says. “And then the next time, we made another banger.” Fernald, meanwhile, was asking for the parts to work on. “But we kind of liked them how they were.”

And so, in 2011, AlunaGeorge was born.

“George had come from a band background, so he was all about writing songs,” Francis says, analysing why the pair clicked so well. “And he was very, very interested in glitchy, alternative, weird production. He was interested in this challenge of how do you get something that sounds super weird and super fresh, but pull it and squeeze it into something that almost sounds normal — to where you be like, ‘Okay, it’s weird. But I get it.’ And I was all about that as well.” There was a bonus to the partnership: “George is also the loveliest human on earth.”

The intention, at first, was for Francis to be framed as a solo artist, with Reid as the behind-the-scenes studio whiz — but that arrangement was soon scrapped. “We had this working method,” Francis explains, where we would go in, and George would be like, ‘I’ve got an idea about a song for my dad. I mean, I just really love my dad, and let’s explore that.’ So we would write a song together about how much he loves his dad. That’s not really what a solo artist does. We were so collaborative that every song that we write is going to have both of our DNAs in a very, very personal way, so we needed to be a band.

“When you start to look at how Black women are treated in dance music, just seeing them as this vocal that you sprinkle over your tracks and this culture of stripping away the humanity of the person‚ that’s really potent"

By any measure, AlunaGeorge was a success, releasing dozens of singles (many of them hitting the charts) and a pair of well-received albums, 2013’s ‘Body Music’ and 2016’s ‘I Remember’, characterised by swooning songcraft, and creative instrumentation and arrangement, paired with, Francis’s chameleonic vocals; playful, seductive, and assertive.

But the biggest AlunaGeorge hits were a series of collaborations with dance music heavyweights, starting with Disclosure’s percolating 2013 tune ‘White Noise’, which reached No. 2 on the UK charts.

“I didn’t want to do it. I was like, ‘No, no, no, I don’t know who these boys are,’” Francis recalls. “And George was like, ‘Maybe you’ll have a fun day!’” Further collaborations, with the likes of DJ Snake, Skrillex, and Diplo’s Jack Ü project, Peking Duk, Zhu, and SG Lewis followed — but to hear Francis tell it, those releases, for the most part, weren’t AlunaGeorge collabs in the way one might think. Instead, on most of them (the DJ Snake release, 2015’s ‘You Know You Like it’, serving as a notable exception), Francis served as more of a hired gun, someone who could add a bit of vocal sparkle to spruce up a club cut.

Francis had no thoughts of branching off as a solo act — she viewed AlunaGeorge as a safe harbour in an industry she was increasingly viewing with wariness, thanks in part to her work as a featured artist. “When you start to look at how Black women are treated in dance music, just seeing them as this vocal that you sprinkle over your tracks and this culture of stripping away the humanity of the person‚ that’s really potent,” she says.

“But I didn’t have to live a whole life of it, just doing these features. I had George, who loves my voice and knows me and cares for me. There was such a huge difference between going into the studio with him — where the way he treated my voice was just so gentle and respectful, and where he was always just so inviting, and where I was able to fly — compared to A&R conversations where they’d say, ‘Let’s just get Aluna on there. She’ll smash it. Put her magic on there.’

“I wrote down something yesterday that occurred to me,” she says, reaching for a notebook. “It goes, ‘If I was a superhero character in a movie, I’d be called Magic, the Token Black Diva of Dance Music — and my superpower is to breathe life into white men’s careers, and then disappear off into the night.’”

But it wasn’t just the features that shaped Francis’s view of the industry. Well before AlunaGeorge, Francis was a fan of the London combo Noisettes and its frontwoman, Shingai Shoniwa. In that band’s early days, their sound was a kind of genre-agnostic post-punky mélange, with Shoniwa serving as a fierce focus.

“I randomly saw them in a little pub,” Francis recalls, “and I was like, ‘Holy shit, I’ve never seen anything like this.’ I was so entranced that I fan-girled, and they invited me to jump in their van to go to their next gig. Shingai was doing it — and I was like, go go go!” But within a few years, both Noisettes and Francis had undergone a shift.

“I saw their career move to a peak,” she says, “and by that time, I already had a label so I knew how they talk to artists, and they know how to squeeze your creativity, especially if you can’t fit a box. And so they had to go pop, like some ’60s kind of thing. Now, I personally know this woman, and I knew this was not gonna go well. She’s a Rottweiler, not a ’60s diva princess. Of course, it didn’t work, and I was really sad about that. I mean, someone who had inspired me to even do music — for them not to be able to make it in their lane, I was like, damn.”

So no, I was not thinking about being a solo artist,” she continues. “I would compare it to being thrown to the dogs. I would get eaten alive. And spat out!” And besides, Francis was happy with her role in AlunaGeorge, serving as the face of the duo and helping to shape the sound through her role as what she calls a “verbal producer”.

“I’m not wearing my ears out with engineering, so I’d be able to come in with a different ear and say, ‘This works, that doesn’t, we need to move that there, and then turn that down.’ Which can annoy some people, but I’m very diplomatic about my approach.”

By the time ‘I Remember’ came out, the AlunaGeorge partnership was running like a well-oiled machine. “It had gotten to a point where you could probably hang us from our legs with no instruments and we’d still make a song in a day,” Francis says. “We were just pooping songs everywhere.” It had almost become too easy. Before long, a nagging thought was running through her mind.

“I realised I was scared,” she admits. “The fear was that I’m not good enough to be a solo artist. I don’t have enough me-ness. But I’ve basically lived my life going directly toward the thing that terrifies me most — so I thought, ‘alright then, going solo will be the next thing I do!’” But having never worked as a solo artist before, she had to come up with a direction.

“I was in the hot tub,” she recalls. “I should still live in a building with a hot tub! Anyway, I was in the hot tub, thinking — ‘if I was one of those artists who could do just anything, what would I do? What should I do?’ And it came to me — ‘oh, I should do dance music!’” That idea might have been spurred by a 2019 performance at Midnight BBQ, an ongoing Black-oriented food-and-music throwdown. Francis was the last act up.

“It was real heavy rain,” she says, “but I had these two Black girls stay till the end. I was thinking, ‘you just ruined a few hundred dollars of hairstyles out there’ — because it doesn’t matter how much glue you’ve put on there, rain is not good for Black hairstyles. That was like, huge for me, like, ‘Oh my god, I get it!’ Seeing those Black girls there for dance music, in the rain, till the end — I mean, that’s all I needed, just two Black girls at the front. I was like, ‘You know what, I don’t need any more reasons than that. I’m just gonna do it for me and those two girls.’”

At this stage, Francis was just learning about dance music’s Black roots. “I remembered there was one tiny piece of information that I could have followed a long time ago — something about Chicago? I was like, ‘Americans, thinking they make stuff,’” she says, laughing. “But as I discovered the actual Black history of dance music, it was such an ‘aha’ moment. Like, ‘Oh, damn — I feel like an outsider in a genre that my people created? But then, however it happened, was in the hands of the white community?’”

That knowledge honed the album’s direction. “I now had permission to do things that I had considered to be wrong and naughty and bad, like using a classic ’90s piano riff with Afrobeats, or putting a dancehall track in a dance album, or even just daring to make reggae, and putting all of this into one bag,” she explains. “And I couldn’t do that with George.”

‘Renaissance’, which featured all the above and more, was released late summer of 2020. Boasting collaborations with Kaytranada, Princess Nokia, Jada Kingdom, SG Lewis, Nigerian vocalist Rema, Norway’s Lido, and others, the long-player was fully cohesive considering its amalgam of styles, with Francis’s singular voice serving as the glue.

A series of remarkable videos for the album’s tracks followed, beginning with the pop-dance cut ‘Envious’, which took Francis and her dancers in the desolate scrub before ending up at what appears to be a black-lit house party. Another highlight was the opulent video for the Kaytranada dancehall-tinged collab ‘The Recipe’. Its directors, Clay Dirkse and Jake Herman, described it as drawing inspiration from the Elizabethan era, dancehall, Midsummer Night’s Dream, Busby Berkeley, The Wiz, and more.

“I look at that now, and it’s like, ‘Whoa, girl, you tried to do a lot in one video,’” Francis admits. “The idea was, well, slavery has been around for quite a while. And what do we think the British empire built their fucking shit on? Slavery. In pictures at the museums, you don’t see Black people wearing finery — but it was our blood that was in those fucking dresses and those jewels and those crowns. So I’m going to do a music video where we get to wear that, and where we live in the castle.” She’s the first to admit that the message may have sailed over most people’s heads. “I think people were more like, ‘Oh, this looks like dress up!’ It’s not like I have an essay next to the music video.”

A few months before the album’s release — and just a few months after the murder of George Floyd, in the summer of BLM protests — Aluna released, via social media, a searing open letter to the dance community. “I need to challenge the ‘dance music industry’ on its long-standing racial inequalities,” the letter read in part. “We not only need to give credit to the artists that created the genre, we also need to establish a long-term plan to secure a healthy future for dance music that is culturally and racially inclusive.”

“Two things motivated me,” Francis says of the letter. “One is that every white producer that I’ve worked with wants something from the Black community. And the other is, if you said to every music lover at festivals, ‘Hey, you know how everyone’s white here? We could either keep it like that, or we could have a mixture of people.’ Everyone would say, ‘A mixture, please!’ No one’s asking for this monoculture. The people on the ends of it are constantly looking outwards towards people of colour — but why are there no people in the centre of this industry, the business people, doing anything about this monoculture madness? And it’s imploding. It’s eating itself up from the inside.”

“That letter,” she adds, “was appealing to the music lovers, the musicians and the producers: ‘Let’s take the genre back from the businessmen for a while. Let’s collaborate. Let’s sort our ecosystem out.’” The Noir Fever festival is one way in which Francis is attempting to do just that.

Like most everyone else, Francis could see the lay of the festival land — and for the most part, it was overwhelmingly white.

“And people would be like, ‘Well, who should we put on there?’” she says. “They wouldn’t say this in so many words, but what they would be [implying is] that there aren’t any Black dance music artists.” But as she learned about the roots of dance music, as well as through prepping her own DJ sets — during the pandemic, she started a mix series called Aluna’s Room — she became something of an authority on the subject.

“When we were trying to work out what the lineup would be,” she explains, “we actually had way too many artists. There’s too many for one festival! So if anyone wants to say to me they don’t know how to find these people, I can say, ‘Here you go, just take these artists and put them on one of your stages.’ The hardest part of the whole process so far has been trying to narrow it down to the 12 slots that we have.”

Even taking that culling process into account, for Francis, the act of putting Noir Fever together feels like an indulgence.

“It feels really naughty to even have this festival, because at the end of the day, this is like my fantasy festival,” she admits. “If someone was like, ‘Okay, it’s your birthday and you get to go to a festival of your choice, what will it look like?’ I’d be like, ‘Oh my god, that couldn’t possibly be also for the general public, could it?’ Because I have a very particular taste. But it happens to be good taste!”

As far as what’s next on her plate — well, there’s a young child to be tended to first. Francis found out she was pregnant about a third of the way into the production of ‘Renaissance’.

“I was hiding it from everyone. I was living off an old thought, which was that children will end your career, which is why I’d never had children before. I’d be wearing really big clothes, but there’s just obviously something about a pregnant woman where people would be like, ‘Are you...?’ And I wouldn’t say anything.” On November 17th, 2019, Francis announced via Instagram that she had given birth to a girl named Amaya.

Francis is still working with others — there was, for instance, that recent collaboration with Diplo and Durante, a plucky house cut titled ‘Forget About Me’. And though she hasn’t ruled out working on music with George Reid again, she’s already in the thick of putting together a follow-up solo LP. Right now, she’s in the process of narrowing down a slew of tracks, and putting the finishing touches on those that make the short list.

“I’ve always wanted to be the person who’s able to say, ‘This is what this album is going to be about,’ and then make all the songs after I come up with the concept. But I just can’t do it. The way I work is, it just grows and grows. It’s organic. The process happens. I won’t know what it is before I get there, but I’ll know what I have when I’m done.”

The same could be said for Francis’s entire career— it’s doubtful, for instance, that the teenage girl growing up in a nearly all-white suburb, or the struggling young artist living in a London squat, or the face of a mainstream radio-friendly act, would ever picture herself as the face of an all-Black electronic music festival. When you put yourself on the line and get to where you’re going, you’ll see where you’ve been heading all along.