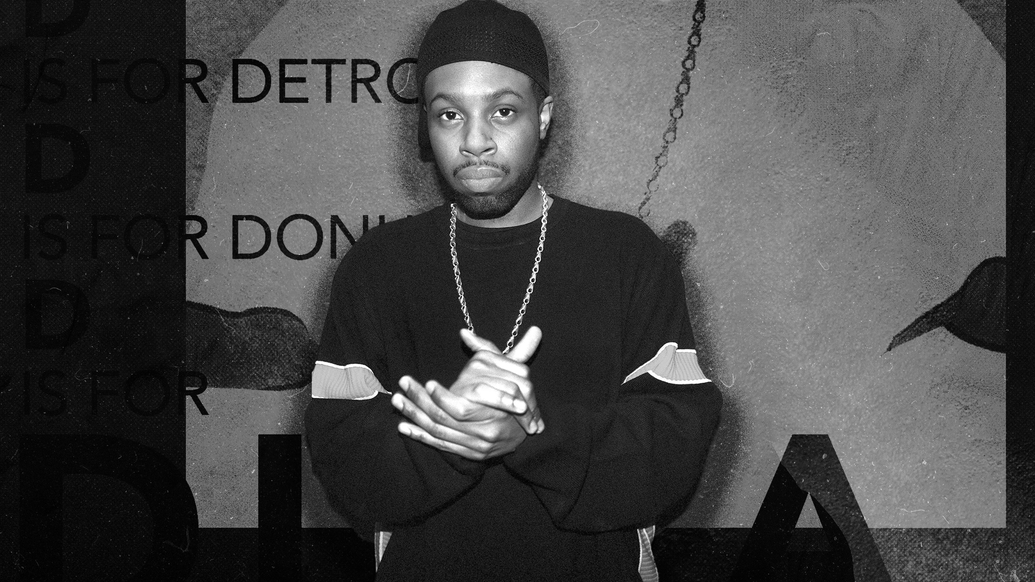

D is for Dilla: the life and legacy of a hip-hop phenomenon

J Dilla changed music with his unique production style and wonky beat patterns. Ahead of an expansive new book on his life and art, Marke Bieschke talks to author Dan Charnas about the enigmatic artist’s impact

D is for Detroit. D is for Dilla. D is for ‘Donuts’, the legendary 31-track collection that James Dewitt Yancey — aka Jay Dee, aka J Dilla — created while in and out of the hospital before his untimely death in 2005, from a rare blood disease, at the age of 32. ‘Donuts’ has been recognised as a summation of the Detroit hero’s production genius, a time-bending compendium of perfectly collaged fragments sourced throughout music history, beat abstractions that verge on the avant-garde — and which can still make grown folks break down in tears.

As a rapper, producer and mentor, Dilla was amazingly prolific in his short life, from singing with his family as a toddler in church through touring half the globe with Madlib and his group Slum Village just before he passed. His peerless way of manipulating samples changed hip-hop forever, introducing a stoned-out, erratic sound that blew apart rap’s stodgy 4/4 tempo with rushed snares, flammed claps, and scattered kicks. Discovered by A Tribe Called Quest’s Q-Tip, championed by the Roots’ Questlove, and pumping out thousands of beat tracks, some created in less than 10 minutes in his basement studio, Dilla rode to the top of the industry at the dawn of the millennium, producing artists like the Pharcyde, De La Soul and Busta Rhymes and shaping the sound of the neo-soul movement with Erykah Badu, D’Angelo, Mos Def and Common.

Dilla Time: The Life And Afterlife Of J Dilla, The Hip-Hop Producer Who Changed Rhythm is the excellent new biography by historian, musicologist, and sometime-producer Dan Charnas, which dives deep (450 pages deep) into the complex story of a figure still so influential, his birthday is celebrated on “Dilla Day” all over the globe. DJ Mag spoke with him about Dilla’s technique and influence, and what it was like to bring his world to life.

You interviewed more than 190 people from all aspects of Dilla’s life, and synthesised all that information together in a way that reads almost like a novel. We’re often inside J Dilla’s head, or there in his basement flipping through his records as he cuts up with friends, or watching him make tracks with some of hip-hop’s biggest names. Everybody had something to say about him. Was it difficult to stay focused on putting together a clear narrative of his life and art?

“There was definitely a lot to work with. I want to start by saying that it’s harder to write the stories of people who aren’t white, due to white supremacist culture’s resistance to preserving them. Related, it’s even harder to write deep, seriously researched biographies of people in hip-hop. There aren’t that many around. I realised that nobody else was doing this, and a decade had passed since his death. I thought, ‘If I don’t do it, it will never be done’.

“I had already created a syllabus of his story for my Dilla class, which began in 2017 at the Clive Davis Institute at Tisch School of the Arts New York University. For the book itself, I ended up concentrating on two tracks — just like much of Dilla’s production. The first laid out the music theory, explaining how Dilla changed things, his mechanics and his influence: the musical time track. I also knew I had to have a biographical track. But that soon burgeoned, because more and more people started sharing their stories. The more I spoke with them, the deeper I went.”

Was there anyone it was hard to coax into talking?

“One of the main ones was Q-Tip, who plays such a fundamental role in James’ life and development. First he said he would talk, then he said he wouldn’t talk. I think what happened with him, and others who were reluctant to speak, was someone came along to tell them that I wasn’t on some bullshit. I think people are very protective of James and his legacy, and want to make sure it’s being done justice.

“On the other side, surprisingly, was his mother Maureen, who shared so much. I think there was a relief that someone was finally telling the whole story. She was eager to dispel a lot of the clichés and false rumours that had grown up around him since he passed away.”

You establish Dilla’s deep roots in Detroit music and history, through his family’s extensive musical past and the Conant Gardens neighbourhood where he grew up, one of the first places in the city where Black people were allowed to buy homes. Then you go beyond that, and map Dilla’s music directly onto the actual geography of Detroit. Its cartography of off-kilter street grids, overlaid with a network of side roads and byways, becomes an ingenious metaphor for his production method. How did this idea come to you?

“I’m an urbanist by training, my degrees are in urban studies and African American studies. So I’ve always been obsessed by the layout, design and function of cities. Sometime around 2016, an old black-and-white industrial film concerning the evolution of Detroit’s street grid began to circulate, and I thought it was just fascinating. I was trying to fit Detroit history, Dilla’s early family history, and the musicology of his technique all together, and that’s when it jumped out at me. The grid is really a conflicted polyrhythm. If you look at the cartography on a musical level, it’s threes and twos placed against each other, but also complexly misaligned on a more micro level. I thought, ‘Hey, why don’t you use the Detroit street grid to teach the theory while you talk about the family that lived in that grid?’ There was every reason to believe that that conceit would fail spectacularly. But that’s the chapter everyone seems to love.”

In the book, you make a strong case for what you call “Dilla time”, as a new way of hearing the world. It’s the iconic “limp” that he created by combining straight time and swing time, in a way that his unique virtuosity with the MPC allowed. Was there a musical moment for you when you realised the conception of Dilla time?

“The first moment of recognition was after I briefly worked with Dilla, producing [rapper] Chino XL. I had been sitting with his beat tape that’s now called ‘Another Batch’ in 1998, listening particularly to a song he had created for Chino called ‘Don’t Say A Word’. I started to think, ‘What’s wrong with those hi-hats? Are they swung?’ So I loaded the track into my Digital Performer, lined up the waveform with the grid, and found out that the hi-hats were not swung, they were completely straight. What was happening was the snare was coming in too early, and it was creating this conflict with the hi-hats that made you think there was a swing rhythm, when there isn’t. That was my first revelation that he was doing something weird.

“The next thing was actually hearing other people be influenced by him: Questlove and D’Angelo on ‘Voodoo’, Hi-Tek and Talib Kweli, Musiq Soulchild, Floetry — all of them incorporated his type of loping, unexpected rhythm. It was the Jay Dee feel. The general narrative was that Dilla turned off the quantise function on his MPC to escape the straight 4/4 rhythm. It took until 2015 for me to understand that this was a programming thing, that he wasn’t simply turning off quantise or free-handing. Quantising or not quantising is just a matter of technique. I’ve quantised and not quantised plenty of times, and my shit does not sound like J Dilla’s.

“It became obvious that he was using the drum machine program, but in a way of setting the elements slightly against each other that fooled your brain. That was his genius. When you swing on an SP-1200, every element swings at that amount. It’s a global swing function. But on an MPC, the swing is severable from element to element, so you can swing the hi-hats but not swing the kick. You can also do shift-timing on an MPC. The common thought was that Dilla was doing something halfway between swing and straight time, but it’s actually straight and swung at the same time. And it’s only possible on a machine. Dilla was a programmer. When he got the MPC in ’97 or ’98, he started to be able to manipulate those functions and create a deliberately misaligned grid in repetitive ways, which became his style.”

Dilla straddled a huge moment of technological changes in music production and consumption at the turn of the century, with the dawn of digital production. But he stayed true to the MPC for a long time, almost as if it was an artisanal tool...

“The MPC was integral because he could play free-hand, he could slow down and speed up samples directly, he could chop things up and scramble them on the fly. He told people that he liked the limitations of the MPC because they forced him to be creative. Listen to a track like ‘Time: The Donut Of The Heart’, where he tricks you into thinking that he’s slowing down a Jacksons sample, but he’s really just playing it at normal speed. It’s a work of art.

“And Jay Dee was one of the great crate-diggers. The digitisation of everything removed the sleuthing part, the need to be well-versed historically, to know who made things. When you go crate-digging, you’re confronted with album art, liner notes, credits, lineage. You’re a historian, literally searching the archives of recorded music, even when you’re in Sammy’s Records in downtown Peoria. That’s one of the things people continue to completely misunderstand about hip-hop: it was created by nerds! Even though Dilla eventually became one of the first laptop producers — by necessity, when he was having health issues and needed to leave his setup behind to go into the hospital — he was still trying to preserve that archival, hand-made aesthetic.”

Dilla Time is full of tales of Dilla’s generosity and sly humour, but the portrait that emerges is more complex than the modest genius of popular imagination. He liked to show off his mink coat and custom Range Rover. He went straight from his mother’s basement to the strip club. He had a huge support network but could turn frosty on a dime. There were times I wanted to throw the book across the room because of how he treated women, or his friends, or his own health situation, ignoring it until he couldn’t. How important was it to show that 360-degree picture of him?

“Writing this book meant telling the truth and getting past the myth. There’s no judgement in this book, and I hope people see that. One of the common myths about J Dilla is that he was humble. It’s a way of worshipping him. But he wasn’t humble. He was quiet, but not humble. His main frustration was that he couldn’t quite make a name for himself, he was always in the background. He was not always great to people, he had a temper, he was a narcissist. He did not form mature relationships with women. As far as what we’ve seen with other men in the industry, he wasn’t a predator or anything like that. I wanted to dig to the bottom of who he was as much as I could, though, and that meant bringing up some uncomfortable things.”

Your previous book, The Big Payback, was a history of the hip-hop music industry, and you trace Dilla’s story through the context of what was going on at the time, with labels swallowing other labels, major albums being shelved, wild deals being struck looking for the next big rap stars — all while grappling with the era of free downloads and sharing music. It was probably the only time that a kid from the streets of Detroit could piss away a $450,000 recording contract because he really didn’t feel like delivering the record the suits wanted. And get away with it!

“The premise of The Big Payback is that you can’t tell the story of a musical genre without telling the story of the industry that helped it rise. The two are inextricably linked. I felt the same way with this story, especially from his time period when the music industry was so powerful, it was still the locus of success, but beginning to fall into this massive disarray. When journalists start talking about the music industry, most of them rely on cliches—the ‘evil record company’. People don’t look into the actual circumstances. Dilla’s record company rep, Wendy Goldstein, was a damn good A&R person with an expansive vision, who brought many of the major hip-hop figures of the time to attention — The Roots, Mos Def, Common — and got them paid. And she got great results creatively and commercially. It was a kind of miracle that this could get done in this industry.

“And J Dilla screwed the record company. He screwed them by not recording in the home studio that he built with their money, but renting a studio downtown. He screwed them by saying he didn’t want to produce his own album, and paying his friends to produce tracks. He screwed them by yanking back an album that they loved and replacing it with one they didn’t. So who was the asshole there? It didn’t make J Dilla less of a genius, it doesn’t make him less of a good person — he was just a good person who was kind of an asshole.”

'You can still hear him everywhere in hip-hop and even pop. If the sound you perfected in a Detroit basement shows up in an Australian indie band two decades later, you've definitely had an effect on things'

The strip club was a huge part of Dilla’s life and art. What was it like researching that part of his persona?

“There’s an old saying in journalism that if you’re going to cover homeless people at a soup kitchen, you have to taste the soup. Unfortunately, I did not follow that edict — partly because those strip joints are gone. I did go to his family church, though! But Tiger’s and Chocolate City are no more, so I had to rely on people’s accounts. You have to remember that this was a time when Detroit had been stripped of much of its infrastructure and services. The strip club was a form of neighbourhood institution. It was the only place you could get a meal prepared with some finesse, where you could make connections; it was the only nightlife in many areas, and a source of income. Dilla made those places a second home because they inspired and energised him. They were where he could impress people with his money and keep his relations with women strictly transactional. But he also fell in love there — Joylette Hunter, who he met when she was stripping, became what you could call the love of his life.”

Dilla’s reputation has only grown since he passed away. How has his influence persisted when so much has changed?

“You can still hear him everywhere in hip-hop and even pop. A little while ago, I went to see Hiatus Kaiyote, and his influence was plain as day. If the sound you perfected in a Detroit basement shows up in an Australian indie band two decades later, you've definitely had an effect on things.”

.jpg?itok=KuC-oMI_)