Daft Punk’s ‘Homework’ at 25: Teachers and Students

At the centre of Daft Punk’s world-beating debut album lay a tribute to the architects of dance music, titled ‘Teachers’. With the help of Neil Landstrumm, DJ Deeon and some unearthed stories, Gabriel Szatan presents an insider’s guide to the Teachers, while CK303 shares a special video mix celebrating the Chicago roots of the duo's sound

25 years ago today, Daft Punk graduated into the hottest electronic act on earth. If you gave every would-be student of dance music a starter pack to entice them, ‘Homework’ would unquestionably be part of the prospectus. And although the fresh-faced and pre-masked Parisians’ 1997 debut album generated bigger radio hits, it is the ninth track, ‘Teachers’, which unlocks the whole course.

The presence of ‘Teachers’ makes ‘Homework’ not just a great record, but a historically useful one. The song functions as a sweeping census of mid-1990s dance music, with a predominant focus on Black and Latin artists of the American Midwest, as well as a cluster from New York and New Jersey, as well as a few choice outliers (The Beach Boys’ Brian Wilson has, at present, not dabbled in acid techno).

It would be easy for fans to listen and assume that this is a shout-out to friends; an ancillary assortment of planets which orbit the Daft Sun. But no: at this stage in their arc, Thomas Bangalter and Guy-Man de Homem-Christo were at pains to present themselves as novices at the service of the music they loved. Like an Oscars speech set to 4/4 time, this was Daft Punk’s celebration of house and techno’s Founding Fathers.

In retrospect, two things about ‘Teachers’ stick out. The emphasis is very much on fathers. ‘Teachers’ is all blokes, a tally which sits uncomfortably, even considering how lopsided the scene was in the mid-’90s. Daft Punk wouldn’t have had to look far: they were buying records put out by Miss Djax; Stacey “Hotwaxx” Hale, K-HAND and DJ Heather were key parts of Chicago and Detroit’s cultural fabric; and if you’re adding explicitly un-DJ names like George Clinton, there’s absolutely room for Donna Summer, Sylvester or Kim English.

Also, the longer you spend with Daft Punk’s influences, the easier it is to discern what records were creatively repurposed on ‘Homework’. Well before they mastered the intricate microsampling of their Teacher and repeat collaborator Todd Edwards, the line between love and larceny does appear to blur.

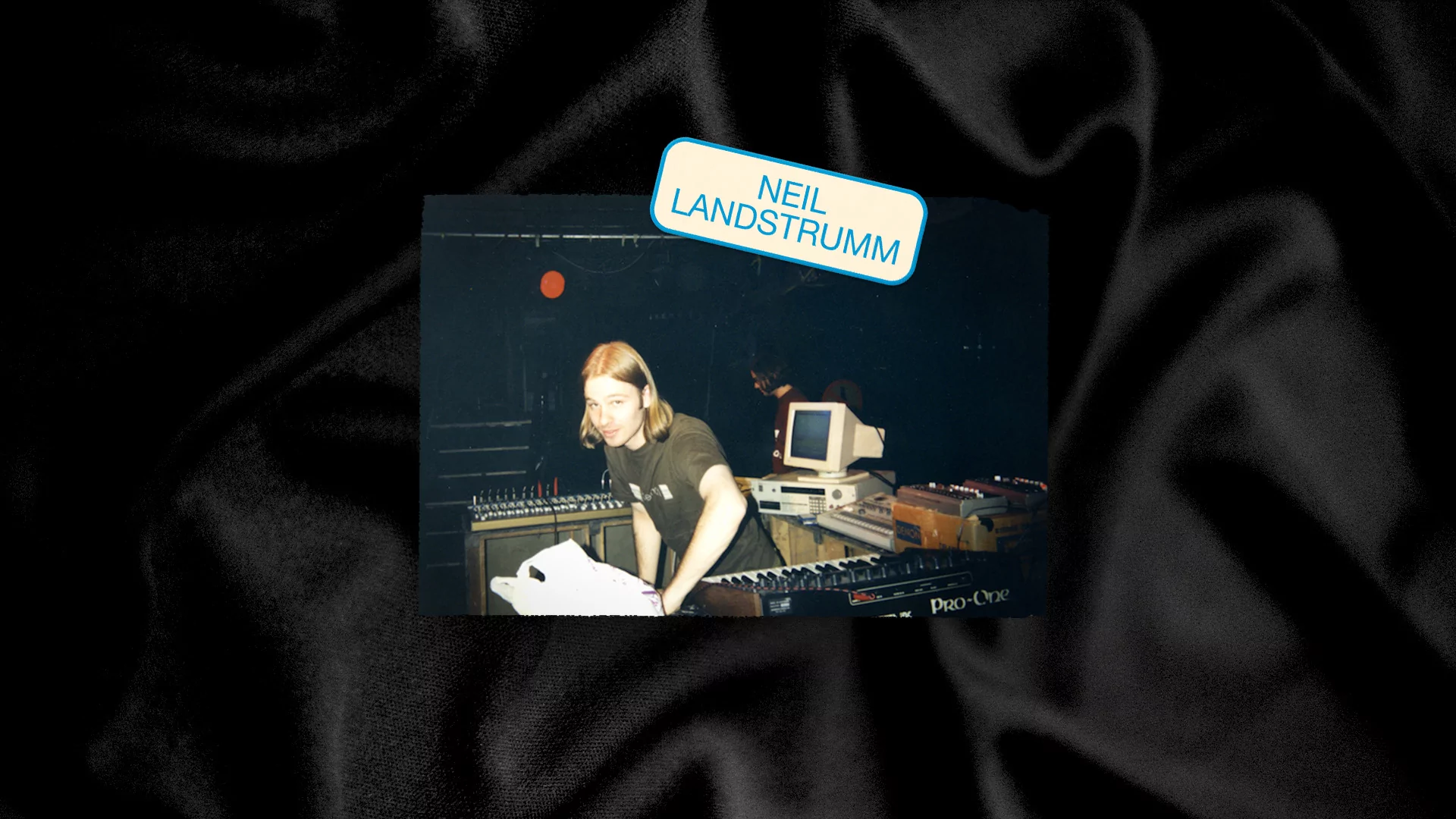

To take one example: malevolent 4am favourite ‘Rollin & Scratchin’’ bears blatant similarities to ‘Sniff And Destroy’, made by Neil Landstrumm, a listed Teacher. Along with more grinding fare on Daft Punk’s third album, ‘Human After All’, this went on to inspire a hugely popular movement of electro-house headbangers in the late 2000s; from there, it was a short leap to the oft-derided maximalist meltdown of brostep and big room. Scratch the hardcore continuum — call that the buzzsaw continuum.

Today, Landstrumm laughs it off. “How many very, very crap imitations of ’90s dance music have been made? Millions? You need talent to pull it off. I can’t stress how much easier it is to misfire than to make powerful, addictive, hypnotic music with a definable soul. Daft Punk might have had access to all the gear, but to fuse all their influences and come up with something massively popular is a skill in its own right.”

‘Homework’ wound up shifting millions of copies, and in doing so, switched on countless passive listeners to artists they might never have otherwise come across. When reflecting on the album’s 25th anniversary, it’s best to head straight to its moral and spiritual core. With that, here’s an insider’s guide to some of the Teachers.

Alongside this feature, DJ Mag can exclusively share a new Daft Punk videomix by CK303 and director Dave Tynan. The film is a tribute to the Black art which influenced 'Homework', using archive material to showcase legendary Chicago dance crew House-o-Matics and the city’s mixtape culture.

Spend enough time in Chicago and you come to realise the city’s passion for music is only matched by its passion for locking horns. Devotees can, and invariably will, debate the merits of first wave vs second wave house until the cows come home. But without Armando acting as a bridge between the 1980s and 1990s, there might be no debate at all.

Armando Gallop got his start in his teen years, as formative cuts like ‘151’, ‘Land of Confusion’ and ‘100% Of Dissin’ You’ became staples with which Ron Hardy electrified the Muzic Box, and would be bundled up on compilations introducing overseas audiences to the Midwest’s creative explosion. With acid house only just cooling on the windowsill (strange as that is to picture today), Armando displayed elite command of the Roland TB-303; many DJs cite him as the first producer to effectively synchronise multiple 303s, corralling overlapping basslines into something punishingly good.

By the early ’90s, Armando was part-revelation, part-kingmaker. Through Warehouse Records, the label he started with Mike Dunn, sister imprint Muzique, co-owned by Steve Poindexter, and a string of records wherein Armando ‘presented’ new names, he had grown into a one-man incubator of talent. Ron Trent, Terry Hunter, Robert Armani, Mike Dearborn and DJ Deeon got their first credits on wax through Armando — although, for the latter, it was an inauspicious start.

“I didn’t have any records out at the time [1994], but I passed a song in the street that I knew was mine”, Deeon tells us. Armando had been so quick to the draw, he pressed up a sample of Deeon’s ‘Yo Mouf’ that existed only in demo form. Ray Barney, founder of Dance Mania and proprietor of key record shop and distro Barney’s, intervened to diffuse any potential friction. That chance encounter worked out well for Deeon: “I gotta give Armando credit. He apologised and that’s how I wound up on Dance Mania in the first place. From then on, Armando would stop by all the time with advice. He was a real good guy, every bit a legend.”

The past tense came rushing up far too soon for Armando. He succumbed to leukaemia in December 1996, mere weeks before his 27th birthday. His death rocked the Chicago community, and remains hard to rationalise (Deeon, a model of South Side stoicism, only flashed vulnerability in our conversation twice: when talking about Armando, and when talking about Paul Johnson). Yet his influence is undiminishable. Armando helped widen the remit of Chicago house music, siring the next generation of Frankies, Farleys and Phutures — and in doing so, progressed the sound into its brilliant second act.

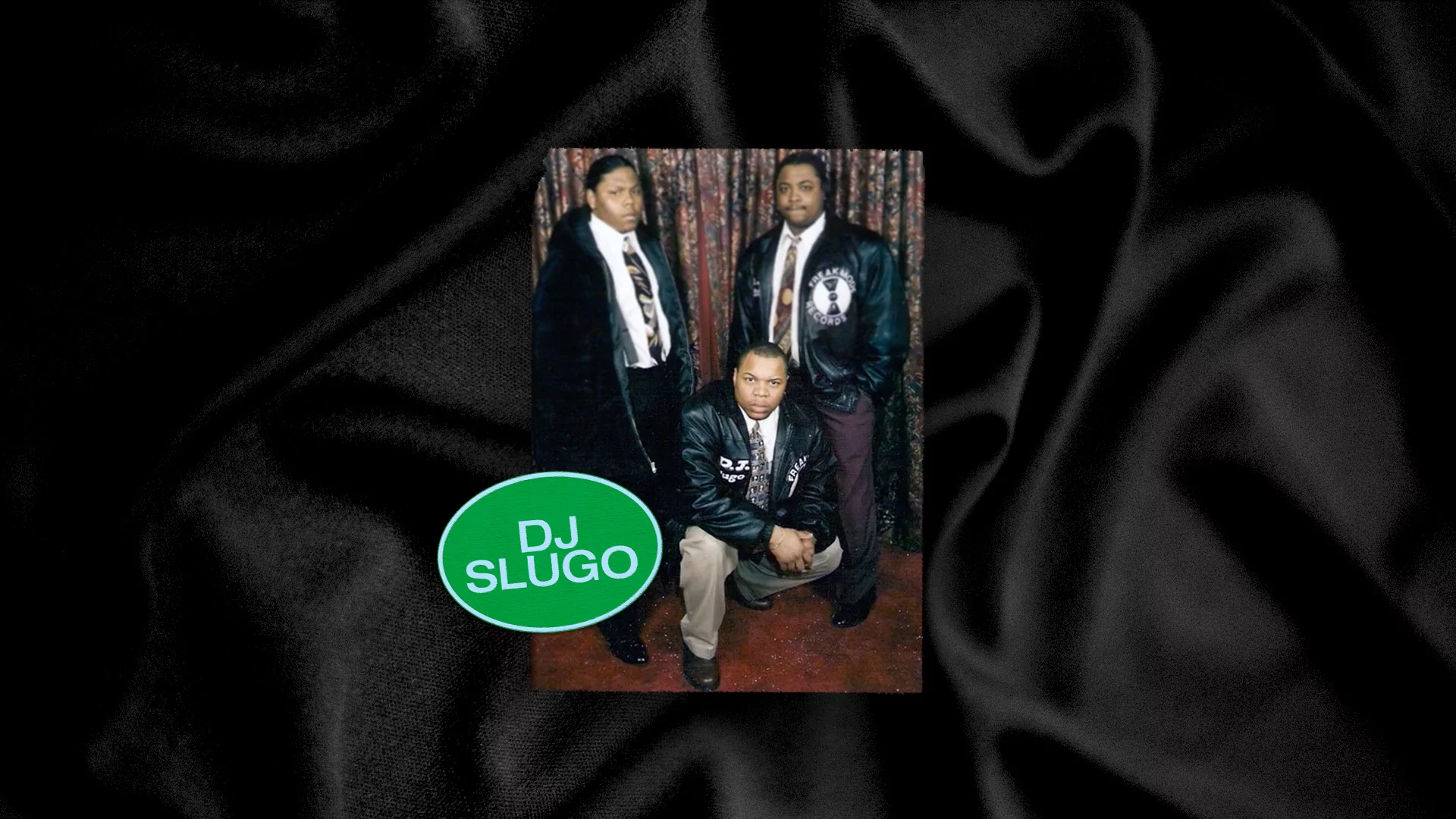

DJ Funk coined the name, but Deeon Boyd is ghetto house personified.

When the style we know today as ghetto house — bouncy and unvarnished 4/4, adorned with ad-libs, chants and a thick dollop of raunch dressing — was percolating, DJ Deeon spied an opening. “I started teaming up with [DJs] Milton and Slugo to corner the market”, he recalls, throwing parties in gymnasiums and churning out mixtapes at speed. In short order, Stateway Gardens projects became “ghetto grand central for the best marijuana, the most legit dances, and the hottest mixtapes too.”

The volume of what spilled out between 1994 and 1997 remains a fun challenge to disentangle. Say the name ‘Freak Mode’ and you could be referring to a popular 12-inch record on Dance Mania, a homemade mixtape series or a Dance Mania spin-off label with matching attire. As the lineage often gets twisted, there’s one important bit of chronology worth clearing up.

It’s well-established that ‘Teachers’ is modelled off Waxmaster and Parris Mitchell’s ‘Ghetto Shout Out!!’. Rummage through mixtapes, though, and you’ll find a similar cut by Deeon named ‘Southside Dj Shouts’ — which the man himself is certain came first. “Mine was more dirty, but a little production polish gave them the edge with DJs in the North, so it stuck. It’s alright. That was a good period for the city.”

While passing through Chicago en route to their first US gig, at Wisconsin’s Even Further festival, Thomas Bangalter picked up a copy of Deeon’s ‘Freak Mode II’ and was charmed to hear his own ‘Roulé Boulé’ as part of the mix. “He put a line out to me and Milton,” Deeon says, “and we kicked it for about half an hour at Dunkin’ Donuts”; a short walk down from where the original Gramaphone Records stood on N Clark Street.

That brief encounter helped to loosen the stiff resistance to their sound at home. “We were just neighbourhood guys, so mainstream DJs in Chicago didn’t care for us. But after overseas DJs started saying they were copying our sound, studying our interviews and having us play, we finally got that respect at home.”

To this day, the progenitors of ghetto house struggle. Milton is incarcerated and Deeon has been through the ringer with chronic health problems and no safety net. Touring helps cover costs but exacerbates the pain. Yet Deeon is sanguine about the peaks and troughs of popularity and recognition.

“This is a young man’s game; what the kids like is not always my style, and that’s cool. You think someone my age can dance the footwork? I’d get tired within five minutes! Culture’s gotta evolve, but when people from the new culture pay that respect back, that’s a blessing. I just want to be comfortable playing my music. The rollercoaster ride keeps me going, keeps me active — keeps me looking forward to the next day.”

Of all the Teachers, Spencer Kincy — best known as Gemini — might have the most acute inverse of promise to career outcome, his life tinted with sadness. An omnipresent figure in the mid-’90s Chicago scene, by 2001 he had essentially disappeared.

Alongside the likes of Glenn Underground (shouted out as “CVO”), Kincy could be seen as a Teacher in the theological sense. Friends tell tales of watching him absorbed in silent meditation in the corner of a party moments before rocking it on the decks. Landstrumm backs this up: “I remember one time when Spencer was over [in Scotland], he walked into a room full of people yammering away and everyone just fell hushed. Spencer had the presence of a basketball player and a philosophical air about him. The man just held the floor.”

Following a string of releases on all the best labels of the age (Peacefrog, Cajual, Planet E), Kincy’s bitter kiss-off to the ‘biz, 1999’s ‘Swimmin’ Wit’ Sharks’, should have sounded alarm bells. One couplet rings especially uneasy today: “But now, instead of trying to understand me / You look me in my eyes and try to underhand me.” He receded from view not long after.

At the turn of the 2010s, a series of investigative reports from 5 Magazine’s Terry Matthew brought fresh eyes to Gemini’s plight, after some apparition had emailed the journalist a complete discography and cryptic clues as to his whereabouts. Interest in Kincy’s life sparked back up, with a clamour to get his music to market and rumours about spotting him out on the streets. Whatever the status of his physical and mental health, the fog of conjecture wasn’t making the industry seem any more welcoming, and it didn’t appear that he was getting the financial assistance he needed either.

Amongst heated debate about the provenance of reissues was renewed attention to one live recording in particular: 1996’s ‘Deep In The Flowers’, a sumptuous exposition of gold-standard house. With an origamist’s knack for arrangement and detail, Kincy’s dexterous mixing style was pivotal to many who came across it — not least Ben UFO, who said in a 2014 RBMA lecture that the set “made me feel as though I could actually contribute something [new] to house and techno just by DJing.”

A 2016 rerelease of album ‘Imagine-A-Nation’ was a beacon for Kincy’s well-wishers: this time, UK label Anotherday had the artist’s blessing, and was ensuring the money actually got back to him. There have been more since, and another reissue, of 1999’s ‘Get Down’, is due out this January. That’s the best way to celebrate Kincy’s gifts today: ignore the scurrilous gossip, buy direct from the source and give the man his flowers.

Okay, so maybe you don’t need us to tell you who George Clinton is. But the impact of Dr. Funkenstein’s blotter-boosted visions on Daft Punk remains curiously undervalued.

Although Clinton flitted from place to place, his spiritual home is Detroit, the testing ground where Parliament-Funkadelic were created in an act of blinding nuclear fission at the end of the 1960s. This link to Motor City has been embellished over time as techno historians point to Clinton as one of the genre’s key building blocks — although, as Clinton has since clarified, he has actually “never been in an elevator with Kraftwerk.”

It was Michigan producer Scott Grooves’ ‘Mothership Reconnection’, which sampled Parliament-Funkadelic strutting through the original ‘Mothership Connection’ on stage, that directly brought the Prime Minister of Funk into Bangalter and Homem-Christo’s orbit. Daft Punk’s edit of the George/Grooves tag-team was released by Soma in 1998, and endorsed by Clinton himself; a huge mark of legitimacy for an emergent duo, and one of vanishingly few official Daft Punk remixes in existence.

Homem-Christo has said that watching videos of old P-Funk tours seared an imprint on his young mind — not least the sight of Clinton clambering out of the iconic Mothership. Come Daft Punk’s Alive 2006-07 tour, it was as if that pyramidal vessel had slipped through a crack in the fabric of time and arrived, newly encrusted with LEDs and ringed by bioluminescent tubing, at dance festivals the world over.

His impact runs deeper still. Dr. Dre, a credited Teacher, more or less owes his entire signature style to Clinton, having recast P-Funk as G-Funk on 1992’s stone cold classic ‘The Chronic’ — an album which pricked the ears of Daft Punk, as they cribbed the midtempo stomp and mewling lowrider riffs for several of the best cuts on ‘Homework’. No Clinton, no ‘Chronic’, no ‘Da Funk’. And if you listen to ‘Teachers’ at 0:31, the utterance of whose name kickstarts the song’s fly bassline? Do we even have to say?

The subconscious association of Chicago dance music is that it defaults to one of two modes: either ecclesiastical house psalms, or filthy call-and-response anthems. One listen to Mike Dearborn’s output dispels that notion pretty quickly.

Alongside Robert Armani, DJ Skull and DJ Rush, Dearborn was emblematic of a step change in North American clubbing in the early-to-mid ’90s. Years removed from the Power Plant and Muzic Box, a fertile Chicago scene sprung up from under the long shadow of recent history. Loft functions and off-location parties boomed; it was that crackle in the air which led to Cajmere-as-Green Velvet to mint the timeless ‘Flash’. Paul Johnson, Dearborn and Armando were periodically bracketed together on some flyers as the Djax-Up-Beats Crew — an association which maintains to this day for Mike.

Early in his career, Dearborn fell in with Dutch rave destroyer Saskia Slegers, aka Miss Djax. Slegers’ 1992 trip to Chicago opened up an fruitful although sometimes contentious exchange between the amphetaminised delirium taking hold in Central Europe and those along the I-94 who gravitated towards tougher fare.

Released in the winter of 1992, Dearborn’s ‘Unbalanced Frequency’ marked the first instance of an American on Djax-Up-Beats. It’s also one of many record titles which function as a pretty useful cheat sheet to his production style: see ‘Intense Muzik’, ‘Unpredictable’ or ‘Razorsharp’ for further proof. Dearborn could summon storm clouds of acid rain at a moment’s notice; his best tracks fizz with untrammelled energy, flirting with overload yet never too far gone.

“Mike’s music broke from the conventional and fairly overdone wobbly TB-303 sound”, Landstrumm explains, “by making acid techno with this citrus sharpness. Add roaring basslines and these kind of atonal clunks-and-knocks really high in the mix, and he ended up with this very sick sound. ‘Chaotic State’ and ‘Birds On E’ are classics.”

Regurgitated hagiographies about what Chicago and Detroit brought to the table have flattened the narrative over time. When it came to dark ‘n hard techno, Chicago could send it with the best of them. Although Rush’s move to Berlin helped bolster his reputation as one of Europe’s heavy elite, Skull, Armani and Dearborn have been nudged out of the frame somewhat. Their horizonless stormers deserve better.

“I was playing a rave at a chateau in North Paris,” Landstrumm chuckles, recounting the first time he ran into Daft Punk. “They were blowing up, with this whole circus around them, yet when they requested to meet, I was just like [deadpans], ‘Yeah, cool, alright.’ We smoked a joint, and although they didn’t have a lot of English, they were keen to hang out. For whatever reason, my lasting impression is that they were very stylish. They had really, really cool trainers.”

Although he’s since gone on to explore pretty much every electronic variant under the sun, it was Landstrumm’s sproingy, raw tools which piqued the attention of those famous fans from across the Channel. Barely 20 years-old, the Scottish producer broke out in 1995, first on Si Begg and Cristian Vogel’s label Mosquito, then internationally through a run on Tresor and Peacefrog. Landstrumm’s debut album was a typically self-effacing comment on the Edinburgh party scene around him. At the rate they were caning it, “we’d all be smoking ‘Brown By August’.”

Landstrumm’s brand of madcap minimalism was inspired by DBX (Daniel Bell), 69 (Carl Craig) and “other Black pioneering artists, like Armando and Robert Armani and all the Dance Mania guys, who had these mechanical jacking rhythms and a sense of fun. The formula was: heavy kick drum, silly noise, short sample, plus maybe a rimshot or a vocal. That was your lot. I loved it.”

His place became a summit for whichever American producer was DJing in Scotland that weekend. “We had Cajmere, DJ Sneak, Claude Young, plenty of characters. Some of them were bewildered as to why this sound had taken hold in Edinburgh of all places, but we all got on.”

In between rounds of more casual patter, Neil would attempt to glean information about what kit was used. It quickly dawned that the stacks of imports captivating Landstrumm were fashioned on Roland R-8s and Akai MPC60s, as well as Casio RZ-1s, which could be picked up for a few quid in local pawn shops. Cajmere’s uncanny metallic monologues were simply being sung down one of his headphone cups. “We thought these musical envoys from another land were built in some kind of flash studio,” he reflects, “but really they used fuck all. And that was deeply inspiring.”

‘Teachers’ only contains one diversion from the roll-call of 43 producers and an occasional affixed “in the house, yeahhh” to fit the beat. In the middle of the song, Thomas Bangalter’s pitched-down voice shouts out DJ Deeon, DJ Milton and DJ Slugo in sequence, then drops in a cute one-bar breakaway: “DJs on the low.”

‘DJs On The Low’ was, typically, the name of both a song and a mixtape. Though he’d been DJing since the late ’80s, 1995 marked DJ Slugo’s de facto arrival as part of the Dance Mania fold — there’s even an inscription on the Deeon’s side of the mixtape telling the world to watch out for the new gun coming through. Slugo had a knack for picking up on neighbourhood slang and bawdy jokes, then quickly flipping what he’d heard into party jams — music directly made for, as well as of, the world around them.

Slugo’s ratchet traxx contain countless variations on Work, Suk and Bang, but what stands out is his sense of humour. This piquant balance of sweet ‘n sour reached its undeniable apex on ‘Wouldn’t You Like To Be A Hoe Too’. Ingeniously lifting the singy-songy melody from a Dr. Pepper commercial and alloying it to a mantra which came off like Sesame Street gone rogue, Slugo minted a scene anthem that happened to be both very filthy and very funny.

After serving time for a nonviolent drug charge, Slugo’s return to the fold in 2005 led him to push into faster tempos. The bonds between ghetto house, ghettotech, juke, jit and footwork seem iron-clad now, but it required producers like Slugo, Deeon, RP Boo, DJ Clent, Spinn & Rashad, as well as Detroit’s DJ Godfather acting as an essential binding glue, to chain everything together in the 2000s.

Being dismissed as the “bastard children of house music” got under Slugo and Deeon’s skin at first, but their music still generates as much passion as any breakaway on Chicago’s family tree. They haven’t left DJ crates since.

One of the more overlooked Teachers came not from Chicago or Detroit, but Mainz.

Thomas-René Gerlach, aka DJ Tonka, and schoolfriend Ian Pooley were in tune with the temple-pressurising acid and Frankfurt trance which abounded in the early ’90s. As teenagers, they released records as T’N’I and Space Cube on Force Inc. — a label putting out jackhammers from Thomas P. Heckmann, Alec Empire and a pre-gaseous Wolfgang Voigt operating under names like Mike Ink and Love Inc. By the end of the decade, a mellow had taken hold.

It’s probable that Bangalter and Homem-Christo’s interest was piqued by Tonka’s vivacious disco cut-ups on Force Inc. US, an American sister label that tended to favour more loopy and less lacerating cuts. Tonka spent some time commingling with the duo in 1996, loafing around in the studio and DJing together at Respect Is Burning, Pedro Winter’s short-lived yet impactful Parisian clubnight.

Though Tonka’s records nestled on the shelves next to those by Gene Farris and Roy Davis Jr. for years, it was his inaugural solo 12-inch that made the grandest splash. He has spoken on several occasions about his assumption that the slowly-unfurling filtered intro of 1995’s ‘Feel’ was mimicked on ‘Around The World’. It’s a fair charge: Tonka was ahead of the French Touch hype cycle by a good 18 months, and you can trace particles of the ‘Feel’ DNA in countless festival anthems over the past quarter-century, including the three little words Daft Punk mainlined into radio and MTV in 1997.

As waves of filter house began lapping at the feet of the pop charts, Tonka became a remixer du jour, applying his signature to everyone from Roger Sanchez and Bootsy Collins to The B52s and heaps of UK garage. So in a welcome exception to a litany of spurned originators, Tonka not only reaped the benefits of being early on the scene, but appears genuinely delighted for his role in something greater than himself.

Daft Life Ltd.jpg?itok=O5ZebR6v)