A decade of DJing: how technology changed the art form

Over the past 10 years, DJing has undergone seismic transformations in technology and process. New styles of DJing have emerged, and some have had huge impacts on dance music culture — even birthing new genres and music production techniques. We speak to four artists who have embraced these transformations to discover what the last decade of DJing has achieved, and what it could all mean going forward

In the last decade, trends came and went — thank you vaporwave, lo-fi house and hypnagogic pop — but some of the most profound and lasting shifts in our sphere were shaped by evolutions in the tools of the trade. A new style of DJing emerged, applying a collagist sensibility to an irreverent and eclectic selection of material.

Frequently described as “deconstructed,” this style was made possible not only by the subversive artistic vision of DJs like Total Freedom and Venus X, but by the actual tools at their disposal. And as globalising forces brought digital technology and high-speed internet to new localities, musical feedback loops delivered radical new sounds from cities like Kampala, Durban, Shanghai and Cairo.

In 2020, some of the world’s most exciting DJs are absorbing these influences and approaching their toolkit with a fresh mindset. The old rules of DJing? They’re there to be broken.

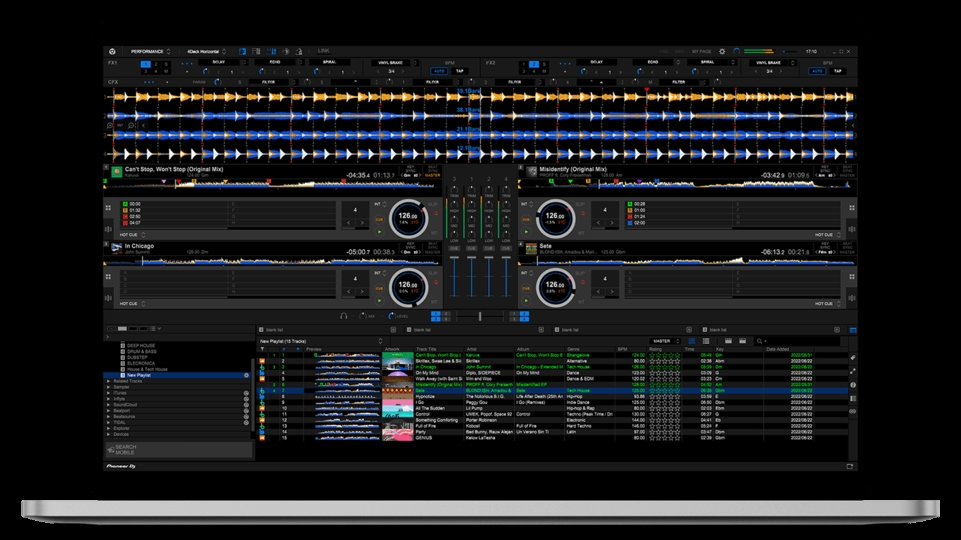

By 2010, software like Serato and Traktor had already produced a generation of laptop DJs, but with faster and more reliable USB technology coming in, plenty of DJs started carrying their whole record collections on a keyring. Crucially, that also made DJing much cheaper, opening it up to bedroom hobbyists and newbies. Critics moaned that “anyone” can be a DJ now — and they didn’t even need to own any records. And for USB-toting DJs, Rekordbox has quietly but dramatically altered the DJing mindset by enabling track organisation in increasingly complex systems.

This shift to digital DJing has made certain skills much easier — most obviously, beatmatching. But through certain fresh innovations — hot cues, wide pitch, and the controversial sync button among them — the art of DJing has been blown wide open, offering new opportunities for experimentation which, in turn, have led young producers to create genuinely new sounds and styles.

DJing with USBs was once ridiculed by the old guard, just as CDJs were scoffed at in the ’00s. The sync button makes life too easy for newbies, they said; skills are being lost. In 2020, a DJ can show up to a gig with a record collection in their pocket, inscribed with metadata that lets them flick through tracks by artist, genre, BPM, or any ridiculous tag system they can invent, as perfected by playlist obsessives like Avalon Emerson and Objekt. Press sync and you’re away.

That divisive little button still has its detractors, but the once-fraught debate over the use of sync has perhaps finally exhausted itself. “As a listener, I’d rather hear someone use the sync button than not use it and trainwreck [the mix],” laughs Teki Latex, the Parisian DJ and Sound Pellegrino boss whose creative approach to blending is totally dependent on CDJ technology.

Teki first came through as part of a DJ duo with DJ Orgasmic, trying to rebrand himself after 10 years as a rapper in the group TTC. He’d never learned to DJ on vinyl — it always looked like a hassle, he thought — and even now, much of the music he plays is only released digitally. Five years ago, he had a creative epiphany with his Deconstructed Trance Reconstructed mix: what he saw as “the ultimate long blend mixtape,” inspired by Lorenzo Senni’s drumless trance experiments. “It was a conscious shift at that point” into “seeing DJing as a construction game,” he says.

The CDJs were core to this strategy thanks to their easy navigation and anti-skipping technology, making long blends easier. Using three decks at once was also crucial, and it’s become increasingly common for DJs to request multiple decks in order to create more elaborate, overlapping blends. But while Teki makes use of some of the new tricks — like the slip function, which he uses to “cheat” at beat juggling — he’s wary of relying on them “otherwise it becomes an acrobatics show,” he says.

“What’s great about getting really technical with your equipment is when you make it seem effortless, but if you use too many effects it hurts the flow of your set and makes people stop dancing. The point is to make people dance more!”

One of the biggest technical advances has nothing to do with DJing as a skill. The introduction of the track organisation software Rekordbox has shifted DJs’ focus to advance planning. A DJ’s collection is unique not because of the tracks they’ve collected, but because of the unique playlists, tags and hot cues they’ve worked out along the way. In 2010, TJ Hertz, AKA Objekt, had recently moved to Berlin where he was working as a developer at Native Instruments.

At the time, he says, CDJs were trying to approximate the experience of playing vinyl; he remembers learning on a “bargain basement” rack mounted set, “the shittest CDJs imaginable.” When the technology advanced, Hertz upgraded to Traktor software. Playing with a laptop and control vinyl opened his mind to the possibilities of playlists: “You’ve gone from a music classification system — from the record bag — to a database. You’re categorising tracks multidimensionally. One track could belong to many playlists — ‘techno’, ‘banging’, ‘opener’, or whatever. Which allows for a lot of freedom in terms of being able to wing it.”

Plenty of other digital innovations have given DJs extra superpowers. When Pioneer CDJs applied the quantise function to loops, allowing a perfect match with the beat, “literally anyone could jab at the loop buttons and make a track loop in time,” says Hertz. “For me that facilitated being able to play stuff that didn’t work as well functionally, by being able to manipulate it.” See also: the introduction of master tempo, which allows DJs to change the speed of a track without changing the pitch.

It’s taken for granted now, but the tool allows DJs to play across greater extremes of rhythm and tempo. Then there’s the ability to save cue points, which makes mixing much faster, explains Hertz. “On a track with an odd number of bars before the drop, in the old days you couldn’t pull it out within 15 seconds and hope for it to come in properly. So [cue points] free you up to play music you wouldn’t otherwise be able to play and to think about where you’re going with your set. You’re not just thinking, ‘is this going to clang?’”

All these tools have encouraged DJs to play with more freedom across a wider range of genres. That in turn has shaped the overall feel of DJ sets playing at the experimental end of the spectrum: chaotic, unpredictable, occasionally discordant. (Though elsewhere, the same tools have arguably sometimes made traditional house and techno sets seem more homogenised and dull.)

The confrontational style that defined the deconstructed club movement was directly shaped by the possibilities of CDJs, and DJ sets in turn have inspired producers to mimic this chaotic experimentation in their own music, creating a feedback loop that continues to reimagine the expectations of the dancefloor.

These developments haven’t been welcomed by everyone. Some DJs have raised concerns that these time-saving tools have lowered the barrier to entry and debased their craft. But there are two reasons to reject this claim. First of all, it’s too late — the tables have turned (sorry). Second, it’s truly undemocratic. Why should we aim to protect “authentic” skills when the artists who are pushing DJing into bold new territory are precisely the people who are playing with these new tools?

The lower barrier to entry isn’t just about technical skills — it’s about financial access, too. As DJ controllers and software have made their way around the world in the last decade, we’ve witnessed entirely new scenes take up the tools to put their own spin on them, resulting in masses of incredible music from unexpected places. (And a certain amount of misplaced controller snobbery.)

When everything is digital, it makes it really easy to be a DJ, agrees Berlin-based DJ and Planet Mu producer Ziúr. “Technology moved forward to make DJing more accessible to everyone, which led to a flood of people with no edge,” she says. “But I like that — I like that it’s accessible and people can just get into the field easily. You don’t have to buy fancy equipment. You can rip the software, buy a controller for 20 bucks, illegally download some music and you’re a DJ.”

Ziúr’s style is part of a lineage that represents the deviant influence of CDJs in the 2010s, often traced back to New York DJ Venus X and her night GHE20G0TH1K, which launched in 2009. On the West Coast, Venus X had allies in Total Freedom and Nguzunguzu, who also paved the way for a generation of chimerical blends pulling from pop and R&B (with Rihanna treated as ruling deity) as well as underground strains like Jersey club, ballroom and grime. DJs like Juliana Huxtable, M.E.S.H. and Lotic — Americans now living Berlin — and Sweden’s KABLAM also led the charge, inspiring untold SoundCloud edits from a wave of bedroom producers.

This new eclecticism, attached to the deconstructed club movement, represented a radical break with tradition. Unmoored from established networks of production and distribution, music travelled freely around the world via SoundCloud and Bandcamp, or through localised scenes and mobile phones via websites like South Africa’s Kasimp3. Its confrontational, sometimes wilfully messy and aggressive style represented an anarchic shattering of “rules” and a plurality of alternative identities.

“There was a wave of people that came up who didn’t give a fuck about genres and were more experimental about what they would put in a DJ set. That’s where I started out from,” says Ziúr. “I play really emotionally. I often don’t remember a set or what I’ve done, but there are moments where I’m allowing myself to fuck up, otherwise I wouldn’t have got to where I am now. If you always play it safe then you will never get anywhere.”

Her own style continues to evolve as she explores the potential of CDJs; recently she’s been playing without headphones, instead relying on visual cues. The sync button remains integral to her wide-pitch approach. Playing across the full spectrum of tempos means it can be fiddly to beat-match perfectly, but “press the sync button once and find [the right tempo] in an instant — and I know I can trust my own tracks because of Rekordbox. That means I have more time for other things. I live for the sync!”

Ziúr’s approach to the sync function is not so much about effecting smooth, seamless transitions but about broadening her options at any moment; escaping the familiar and predictable. At the experimental end of the club spectrum, the last five years have been defined by a growing taste for abrasive textures and disruptive rhythms. Perhaps the human ear craves some degree of mess after all: dirt, grunge, human fingerprints.

Though tools like the sync button were designed to help DJs avoid trainwrecks, experimental-leaning DJs have used these tools to give themselves even more space to mess around, make daring blends, and assert their scruffy humanity. And the influence of this eclectic, collagist style has been heard in some of the most innovative records of recent years by artists like Air Max ‘97, TAYHANA, Oli XL and Ziúr herself, to name a tiny handful.

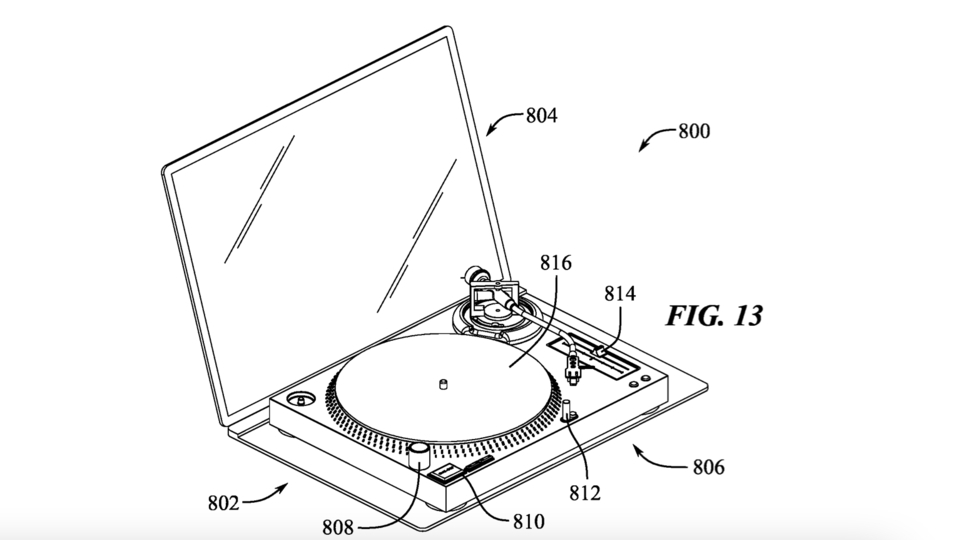

Born in Mexicali and now based in Los Angeles, DJ and producer Siete Catorce has been conducting his own experiments in dancefloor extremism. Like an increasing number of younger DJs, he uses a hybrid setup to play across vastly different tempos — something that wouldn’t have been possible until recently. Having learned to DJ in 2011 using Virtual DJ software, Marco Polo Gutiérrez initially struggled to play sets of his own music, which was “all over the place, tempo-wise.”

But once he was introduced to Ableton, he discovered how to combine live performance with DJing. Realising that he could connect his laptop to Pioneer mixers through their built-in audio interfaces, he began to develop a singular performance style: Ableton for loops, a drum machine alongside, and CDJs on the remaining two channels.

“It’s a crazy way of DJing, or performing,” he says. “But I like songs that are 180 BPM and songs that are 124 BPM — so why not turn the tempo all the way down, make a weird breakdown, and then turn it back up? It doesn’t always have to be perfect, though a lot of DJs have that mentality.”

Marco cites his NAAFI associate Lao as a big influence; Lao’s style also involves extreme pitch-shifting and rapid tempo changes. It’s an approach that’s not so unusual in Mexico, he says, “because the music they listen to is so different — especially going from dembow into tribal and techno. It’s all about the type of music you play.”

So what can we expect from the 2020s? If the history of electronic music has taught us anything, it’s that you never know which new fad or technical innovation will accidentally create a subculture or invent a whole new sound. Some of the latest developments are not so much about music but about data and ownership — specifically, a raft of innovations that could enable producers to get paid every time their track is played in the club. The technology exists — but the potential repercussions are still unknown.