Exploring the relationship between ambient music and mental health

More and more artists and listeners are discovering the benefits of ambient music to our mental health. Here, Manu Ekanayake speaks to artists Meemo Comma, Auntie Flo, CLAIR and KMRU about its therapeutic qualities, and learns how one NHS neuroscientist, James Kilner, is using it to help people with anxiety and depression

Fans of ambient music will know that the genre takes its name from Brian Eno’s seminal 1978 album, ‘Ambient 1: Music For Airports’. Meanwhile, the Cambridge University Press calls it “a type of music, often without a tune or beat, that is intended to make people relax or create a particular mood”. Others might well know it as ‘chill-out’, the tunes you stick on when the afters is winding down or when you’ve had enough for one weekend and would like to get your head down. Or maybe ambient helps you work from home, a situation many of us found ourselves becoming far more familiar with over the pandemic? Either way, you probably have some idea of what we’re talking about when we use the term, even if your idea of it is a bit vague.

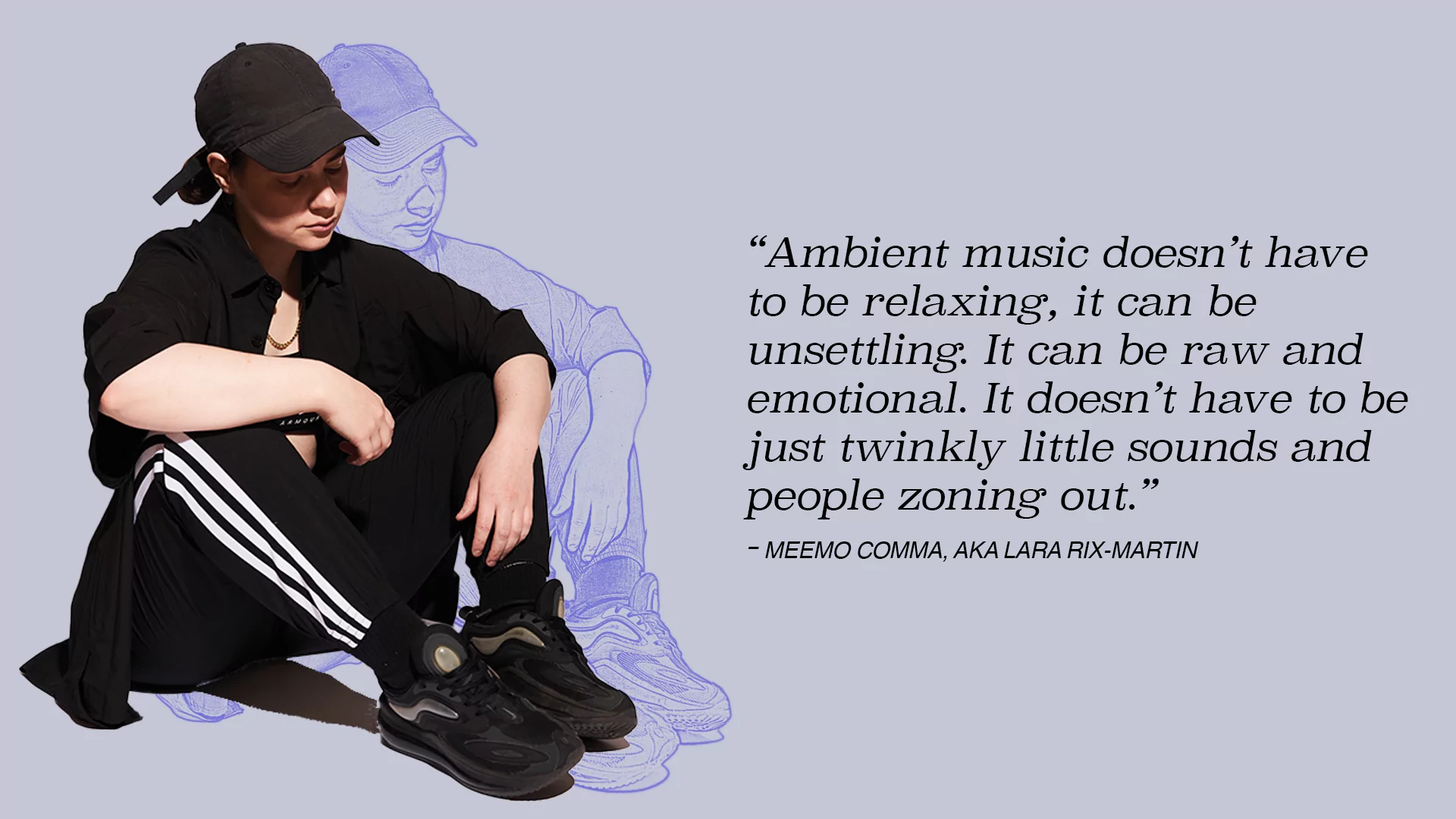

That lack of a precise definition makes sense to DJ Mag, because when we were researching this article, we spoke to five ambient artists (plus one neuroscientist, but we’ll get to him later), and each came to a different definition. “Ambient music doesn’t have to be relaxing,” says Planet Mu artist and Objects Ltd label boss Meemo Comma, aka Lara Rix-Martin, whose ‘Sleepmoss’ album from 2019 was widely considered ambient, though they consider it more experimental music. “It can be unsettling. It can be raw and emotional. It doesn’t have to be just twinkly little sounds and people zoning out.”

Not necessarily all that chilled, then. Auntie Flo, aka Brian D’Souza, who during lockdown started hosting weekly Ambient Flo online radio shows (which became an eponymous 24/7 online radio channel), agrees. “It can be some of the most engrossing and enveloping music that exists,” he explains, “because it’s not necessarily linked to a definitive time structure and metronome. Like when you’ve got a kick going at 120-something bpm, it’s very easy to lock into that. But ambient is a lot more free and flexible, and that’s where my interest lies.”

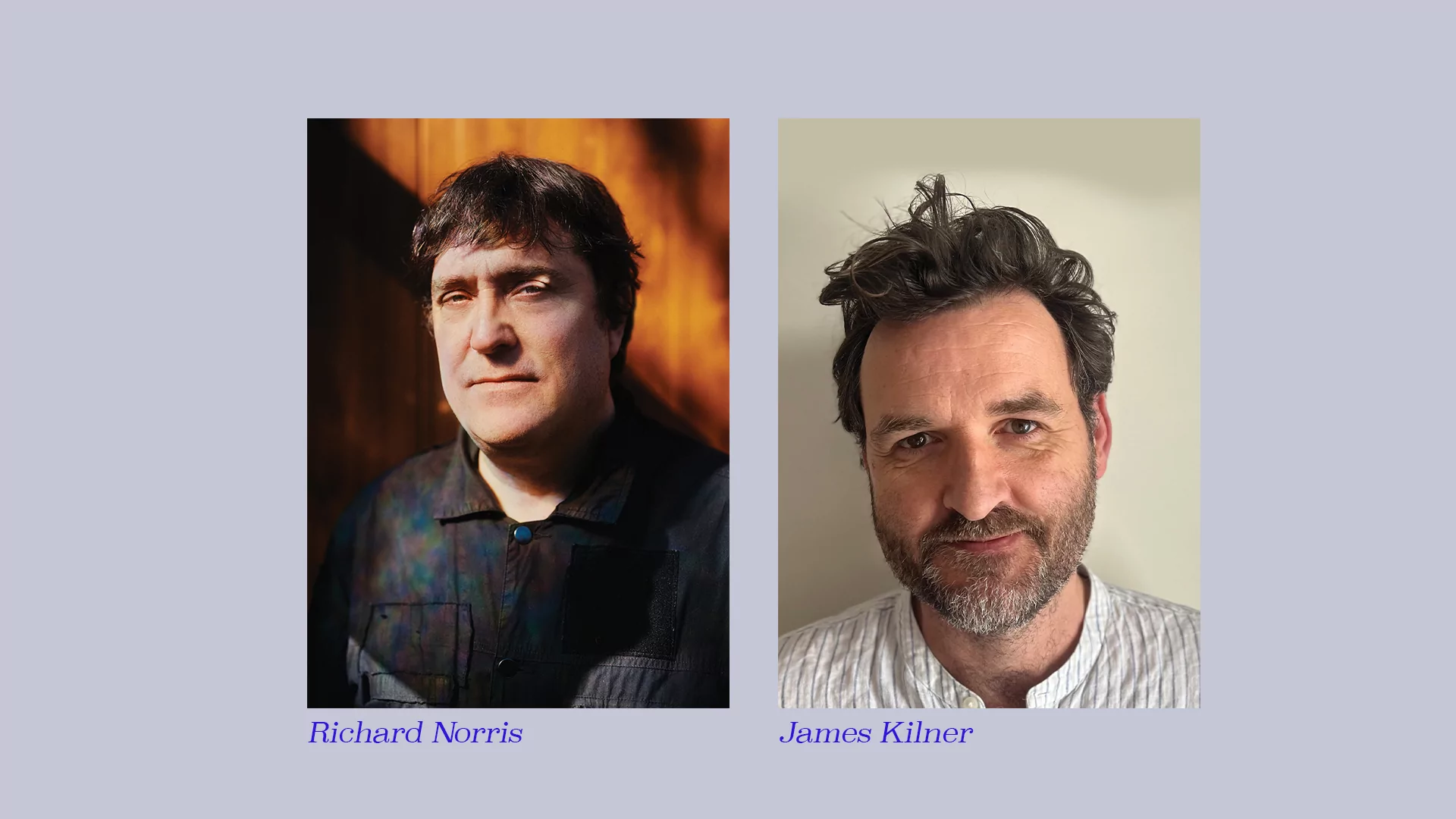

So ambient is a hard genre to define, even among makers of it. Perhaps the hardest to define, even in the thoroughly subjective world of modern electronic music. But however you characterise it, when DJ Mag heard Richard Norris’ new album album ‘Deep Listening 2019-2022’, we were blown away by his recent ambient work, and we had to speak to him. And when we found out he’d been working with a UCL neuroscientist, Professor James Kilner, for years on what ambient music can do to help with people’s mental health issues, we had to investigate further.

“The album is a kind of primer for people who haven’t been exposed to my music over the last few years,” Norris says. His rep in UK dance culture goes back to the early days, when he co-produced the 1988 album ‘Jack The Tab’ with experimental music OG Genesis Breyer P-Orridge and topped the charts worldwide with the track ‘Swamp Thing’ as part of electronic live band The Grid, with ex-Soft Cell member Dave Ball. More recently, he teamed up with Erol Alkan for the psychedelic remix/re-edit duo Beyond The Wizards Sleeve in the 2010s, and released his solo psych project The Time And Space Machine too. So while he’s always pushed the boundaries of dance, this is clearly a new direction.

“I’ve been creating a lot of music, some of it ambient, some of it more abstract, some of it more cinematic,” he tells us. “So I put my last three years’ work all together with newly edited short versions on one album to introduce this music to a wider audience. It shows me thinking about music in a different way: not thinking about beats, not thinking about drops or breakdowns. It’s more abstract, in a way — without song structures. It’s much more of a free-for-all feeling than what I would normally be doing. So even though it’s not beat-driven, it’s still electronic and is informed by years of clubbing. I think there’s still a certain sensibility that comes from having been involved in club culture as well.”

Norris came to this new direction via some personal strife, which is a common theme among the artists we’ve spoken to. “Six months before lockdown, I was living on Portobello Road in West London, and there was chaos outside every night, with various locals fighting each other in some kind of street war. This made my family and I feel a bit boxed in, obviously, so at first I was just trying to create a place of safety within my studio. First off by meditating; I’ve been doing transcendental meditation for 35 years, twice a day for 20 minutes. But instead of using just the usual transcendental mantra [a sound which is used to focus meditation, like the ‘Ohm’ chant for example] I would be listening to drone music with it.

"Particularly stuff like [French electronic composer] Éliane Radigue, which is a kind of techno-based drone using a huge old ARP 2500 synthesiser. She was working with the early Parisian electronic gang of Pierre Schaeffer and his group, creating these amazing loops, which are called ‘Trilogie De La Morte’. I was listening to that, and for some reason the sound of it made me stop my mantra and just listen to the sound. I realised that with the mantra, even though it’s not something you think of in terms of words, it didn’t seem as immediate as the music. This seemed like a different kind of meditation, possibly a stronger type.”

This led him to making 20-minute pieces, the same length as his daily meditations, which he eventually shared via his Group Mind label and Bandcamp page. As to the sound itself, Norris “was using various techniques to make it calming; so there are no sudden bursts of drums or things that the brain wouldn’t recognise. There’s no ‘shocks’ in it. Certain high frequencies I took out, to try and create an ‘analogue bubblebath’, as Aphex Twin would say,” he laughs, referring to the classic EP’s title. “Something very warm and safe. I definitely think of it as a space, as a landscape.”

Now this is all very well, you may think, but can such music really help people with their mental health? The short answer, very simply, is yes. DJ Mag consulted Professor James Kilner of UCL, who joined our Zoom chat with Richard Norris. The two met socially seven years ago and have since been working together, because, “We have shared interests in music and the role it can play in people’s lives”, as Kilner puts it, as he kindly explains his work in ways DJ Mag can understand.

“I study neuroscience, which is to say I study the brain. Specifically two areas: how we move and why we move. How we process information. And my main focus right now is the connection of our body signals [physical signs we are stressed or unsafe] and our brain. So there has been this subconscious idea over the last 20 or 30 years that the body carries the brain around and supplies it with oxygen and nutrients and whatever else it needs. But now we have finally got back to the idea of a two-way interaction; between things like our heart rate, our breathing rate, the speed at which we move. All of which influences our state of mind or how we think about things, or how we perceive things in the world. It’s a much more direct connection between those signals. This is why things in our environment that can change our bodily signals, either directly or indirectly, can change our emotional state.”

So creating a beneficial environment, soundtracked by ambient music, can soothe people who are experiencing anxiety or depression. This is something that Kilner and Norris have done recently for the NHS. Norris tells us, “We’ve started doing some studies with a large clinical practice in York. Just getting small groups of people to sit and listen to this music. We gave them a structure to it: ‘Let’s all do this at 7 o’clock for 20 minutes and sit down and reflect and see what happens’. And I think being given that instruction by a doctor helped, too.

“There are various levels of placebo that could be working in there,” he continues. “The idea being that, ‘If the doctor says it’s going to work, then it is going to work’. That was an interesting thing and we very much want to do more of it. The response from that community was that they very much wanted to do more of it — and for their staff as well as their patients. So it’s a matter of working out ways of rolling that out. Because of course people can just put on Spotify or hospital radio or whatever, but it would be great to do it in that specific way — even site-specific work which looks at what architecture could affect responses as well.”

Someone who has personal experience of how environment affects anxiety is Glaswegian ambient producer CLAIR, aka Clair Crawford. After many years working in dance music as an artist manager and creative, with skills ranging from web design to jewellery making, she finally felt confident about making music in 2016 as she created what would become the final track on her 2021 debut album, ‘Earth Mothers’: ‘A Witches Bedroom Chimes’.

“My anxiety levels were through the roof at that point, and it helped me get through that,” she recalls. “I was tired of working in the music business and I’d been through a violent traumatic incident as well. My back was really hurt so I couldn’t get on the work bench and make jewellery. But I knew I had to create something. That’s when I submitted a track to Stuart McClean’s The Dark Outside festival, where they play 24 hours of unreleased music off an improvised radio mast in the forest of Dumfries and people hear it on these little transistor radios as they walk around. It was a really healing experience for me.”

This healing vibe is something that Crawford found continued for her during the pandemic. “When lockdown happened, like a lot of people I was spending time in the park. I started micro-dosing with [magic] mushrooms and spending a lot of time in nature; playing with birds and squirrels, that kind of thing. It made me start to see things differently. Basically, I think humanity is not designed to have so much technology around us — it’s evolved faster than we have. Things like the bombardment of social media and people not having enough rest, as we live in such a fast-paced environment. And the constant noise as well, we are constantly surrounded by an absolute racket, especially if we live in cities. That has a subtle effect wearing down on your brain. Everyone seems to have anxiety and stress, whereas the pandemic, as much as it was the heaviest thing societally, I really liked it personally as everything was really quiet. There was hardly any traffic around, and I felt like I was really connecting to nature.”

The sheer loudness of modern society is an idea that resonates with Auntie Flo’s Brian D’Souza too. “We’re living in these dystopian urban environments and it’s having an adverse effect on our health,” he says when we meet at his North London studio. “I mean, I can’t survive the Tube without noise cancelling headphones, and even then it’s crazy loud.”

The need to reconnect with nature is also a big part of the Ambient Flo online radio station. “Back when I was starting the radio show during lockdown on Saturday mornings from my garden, as I was just streaming from my phone, as well as the music you’d get a lot of nature noises, and I’d get comments like ‘I really liked the tunes but I enjoyed the birdsong too’. That’s why on the station there’s a channel of music and a channel of nature noises, and you can mix the two if you want. I realised a lot of people didn’t have a garden, or couldn’t get to a park — perhaps as they were isolating — so at least listening to the sounds of nature must be of some benefit.”

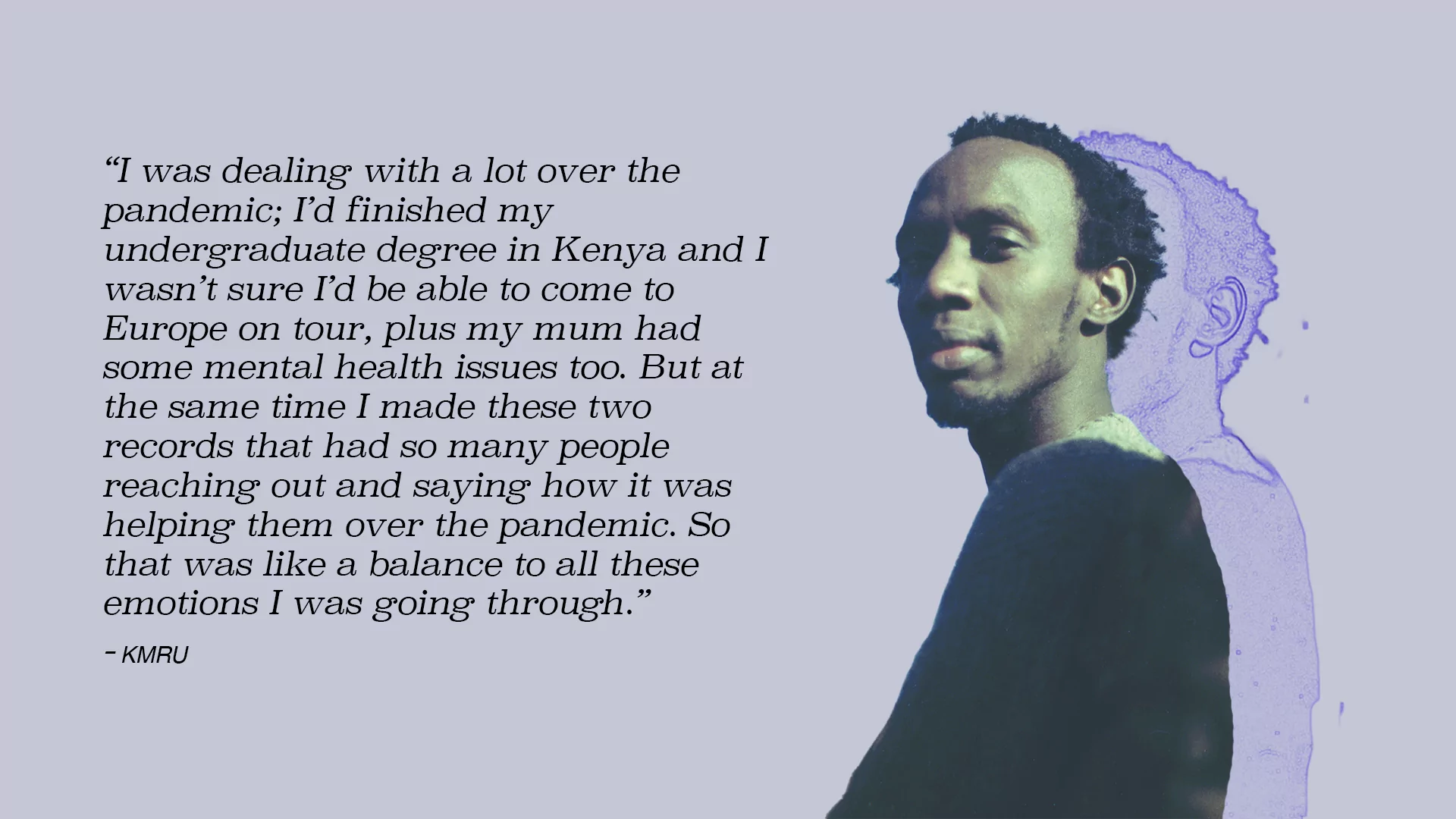

Similarly, Berlin-based artist KMRU, who hails from Nairobi and whose 2020 album for Editions Mego, ‘Peel’, was hailed as a contemporary ambient classic, tells DJ Mag that it’s slowness he’s looking for when he’s making music.

“Over lockdown, I’d feel like, ‘I’m making this music to slow down and have company’. I’ve always been an indoor person, staying in to learn how to make music. I was dealing with a lot over the pandemic; I’d finished my undergraduate degree in Kenya and I wasn’t sure I’d be able to come to Europe on tour, plus my mum had some mental health issues too. But at the same time I made these two records that had so many people reaching out and saying how it was helping them over the pandemic. So that was like a balance to all these emotions I was going through.”

To finally return to Professor James Kilner, he agrees that slowing down is key. “One thing I often say to Richard is that in modern society, we don’t value time to just do nothing. We’ve always got a phone or a laptop, so the idea of just letting your mind wander is probably more needed than ever. We have to work to find that space — like Richard does with his two 20-minute daily meditations. Now both my parents are reverends, and while I’m not religious, I do find it interesting that most religions have an idea of prayer or self-reflection, which is meditative. Even church choral music has some similarities to ambient music. So I think there’s a fundamental benefit there.”