Gauteng style: a history of house music in South Africa

South Africa's love for house music flourished in the early ’90s as the Apartheid era ended, pushed primarily by DJs in and around Johannesburg and Pretoria. Now, it's a focal point, filled with local styles and stars. Martin Guttridge-Hewitt heads to Gauteng to learn the story of the scene’s origins, and the risks its pioneers took to pave the way for its thriving industry today

It’s sometime after 11pm on a warm December night when DJ Mag meets Vinny Da Vinci. An understated guy, this giant of South Africa’s club underground long since reached boss level among fans of 4/4 in his homeland and beyond. A modest-sized crowd are locked into his deep rhythms on the small outdoor terrace at Tsweu Street Lifestyle Café, with resident Mr Slow soon taking charge, ensuring the tangible vibe in this typically informal township venue continues. Beyond the entrance, these ends of Pretoria’s Mamelodi neighbourhood have long held a reputation as a nightlife destination, offering several addresses designed for drinking and dancing. But our evening is all about Monday Therapy.

This weekly session also involves DJ Christos, another of the country’s dance music godfathers. Among many other things, he’s responsible for co-founding (although is no longer actively involved in) the legendary Kalawa Jazmee Records, a cornerstone of the kwaito scene, starting South Africa’s annual Dance Music Summit and, alongside Da Vinci, creating the iconic duo DJs At Work. Both men claim musical legacies stretching back to the late 1980s, and were pivotal in establishing house music across Gauteng.

South Africa’s smallest but most populous province, the nation’s largest city and economic powerhouse is here, Johannesburg, as is the executive capital, Pretoria — unofficially regarded as ground zero for SA deep house culture. Arriving from the UK this morning, we’re here to try and learn how these artists and others first began spinning tunes from the US, UK and Europe, creating the soundtrack to a period of socio-political change on a scale unmatched anywhere in the world.

“I’ve been a DJ for 30-plus years, I just loved music growing up. I was in a household where there was music playing all the time, not necessarily dance — soul, R&B, jazz,” Da Vinci tells us after the gig. “DJ culture started coming through the love of music, but mainly a clique of guys, friends of mine, some sadly have passed on. One — Dion, DJ Shoes — had a DJ console with turntables, mixer, tape deck, and equaliser built in, so you just plugged the speakers in. We were booked for weddings, birthday parties, playing anything that worked.

“That was around 1986, maybe 1987. As years went by, my first experience of a nightclub happened. One opened in my ‘hood, Ship Ahoy, and I heard about a guy there, DJ Correy,” he continues. The two struck up a friendship, with Da Vinci often standing in the booth simply to watch, listen, and learn. “Time went on, another club opened in the township, a Sunday place, Cherry’s. We’d go, chill, hear music, and it became our regular place. There was a resident, one day he wasn’t there. I was having a drink and there was no one to play, they were using a CD or something. A friend knew I’d learnt the tricks and told management.”

Driven home by the owners to collect some vinyl, one of Da Vinci’s first sets followed through belt-drive turntables, and as the night ended a residency was offered. Beginning in 1989, he had a regular platform for marathon all-night mixes, taking in everything from Milli Vanilli to hip-hop, although it was club remixes of artists like Madonna that began turning him on to the deeper ends of producers like Louie Vega and Frankie Knuckles.

“Some had friends at airlines and would ask them to bring tracks back in their luggage. Others would pay people to be couriers and get tunes into the country. Whether you call this bootlegging, or contraband, you made the most of any way you could get at the music.” – Da Vinci

That genre-straddling approach was a product of necessity as much as design. Early township DJs often played open-to-close so needed to keep things varied, and had limited resources to buy tracks. So-called “international music” was born, a term that referred to anything floor-friendly but not domestic, from synth-pop to disco and early house. The Apartheid regime’s policies of enforced racial segregation and minority white rule, now approaching their final days, also created stiff barriers in terms of events and access to music.

“In the ‘hood, it wasn’t that difficult to run parties. These places were called ‘homelands’ at the time, we had our own president, so it didn’t really belong to South Africa, it’s in the country but different, and we had our own ways,” Da Vinci says. City centre areas and their white clubs were a different story, he explains, meaning his bookings at those venues only really began after Apartheid ended.

“But would you believe it, DJ Correy was already playing [downtown],” he continues. “Obviously, he’d have problems when he wanted to leave a club — authorities would be on his case. I’d still go watch him, and I knew there would be problems on my way home. But we didn’t care. We knew we loved this thing and wanted to be there.”

Sanctions imposed by the US also caused issues, particularly with American vinyl imports, so UK-pressed reissues were more commonplace. As Da Vinci recalls, though, workarounds could be found. “Some had friends at airlines and would ask them to bring tracks back in their luggage. Others would pay people to be couriers and get tunes into the country,” he says. “Whether you call this bootlegging, or contraband, you made the most of any way you could get at the music.”

Starting DJing in 1988, after spending his early teens working at Record World peddling jazz and other genres, Christos was also building a reputation as someone in the scene with an ear for beats, and scant regard for politics and segregation. A young white man, he played both downtown spots and areas racial laws were supposed to place out of reach, and tells us that specific releases were banned from sale by the government, although censorship mainly affected “more mainstream stuff”.

“I was working in townships before [Apartheid ended], and I’d get a lot of shit if I was caught. I mean, even name-wise I was never Christos — I changed my name like five times to avoid the cops,” he recounts. “I’d learnt to mix as I could be in clubs with the equipment — Technics 1200s. I met Vinny at Club Cherry’s and he was doing the same thing, trying to mix, but on belt drives, no pitch, trying to force the song, slowing vinyls down with a brush.

“When I met [DJ] Tim White we set up our own record store, Megatrax, selling 12”s in the early 1990s. This is where the cornerstone of house music in the country started, as we’re talking about Black South Africans really getting into this,” he says of a business that would give birth to House Afrika, the seminal and multi-platinum-selling label co-owned by Da Vinci.

Christos explains how jazz and soul influenced the tunes that first took over clubs. “From a house perspective it was always the musical stuff that worked… To give an example, we sold over 11,000 copies of Frankie Knuckles’ ‘Tears’. I remember at the time we were told that was among the biggest numbers in any country.”

While vinyl and venues unsurprisingly played a huge part in South Africa’s house music love affair, the sound was also finding a footing through tapes and transport. Meanwhile, some of the biggest dance events Gauteng would see post-Apartheid were rooted in block parties held before the change of government marked an end to state-sanctioned oppression for the majority.

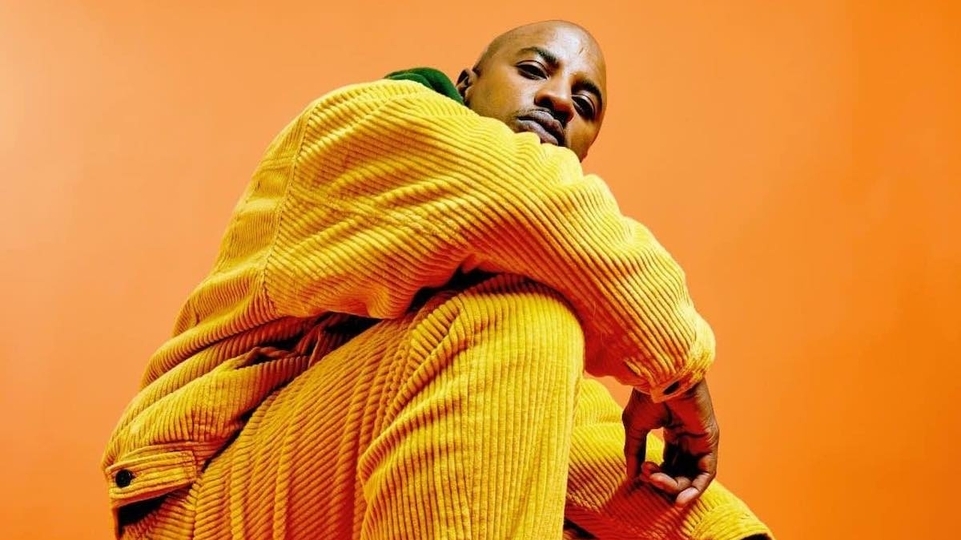

We meet the tall, shaven scene figurehead Positive K at FoREAL, a DJ and production school in downtown Pretoria run by another bona fide stalwart, Miggs. Today, on top of relentless DJ bookings — he plays four dates this weekend — Positive K works with organisations on cultural projects aimed at disadvantaged communities. Four decades back, he was growing up in the Ga-Rankuwa township where, after losing his father at an early age, he and his younger brother were raised by a single mother comforted by music.

“I started collecting records like Duran Duran, Pet Shop Boys — a lot of pop artists. As time went on I became interested in house music,” he recounts over beer and chicken wings in the afternoon heat. “By 1984 I was saving my lunch money to buy records. Me and my friend would borrow each other’s as we couldn’t afford much vinyl, and chill in the house on Saturdays playing records. Then the art of mixing took my attention.

“There was this guy called Chris Moseneke. He’d play at Club Gemini, and I had a mixtape of his. I mean, he was really mixing. I was so interested in how he was doing this,” he continues, referencing a venue Christos and Da Vinci later held residencies at, which, alongside Arena, Ellesse, and Carnalita, is considered hugely influential by house heads in Gauteng. “Gemini was one of those clubs on another level. The sound was world class, everything was very nice. It was the 1980s, we were too young, but Chris — who I’d become friends with — said to join, but that I had to stay in the booth due to my age. I went and fell in love.”

His mother bought him a pair of belt-drive decks under strict agreement his schoolwork would not suffer. Hours before and after class were dedicated to learning the craft, before plans were hatched to host a neighbourhood party, understanding that if the sound was good enough attendees and DJs would want to be involved.

“My first event was at my mother’s house, in the first week of December... Some friends stole a bus and used it to block the street, so it filled up... I remember thinking not many cars were passing by, but didn’t realise what had happened. The following day police came and said we had to cancel any future parties and find somewhere to do things properly,” Positive K recounts. “Properly” came in the form of 60s Parties. Launched with Molefi Setlaleleng and the sadly deceased Seleko Monare, whose family’s Monare Farm provided the venue, around 14 people attended the first, named after the 1960s and ‘70s dress code. By the Millennium, crowds had swelled to over 10,000.

Around that time, Positive K’s ‘Plus 8’ compilation CD dropped and became an instant classic, but the cassettes he had been selling for years before were just as significant. Money earned through this enterprise paid for vinyl, which secured gigs. As he says with a wry smile, one guy would even travel by bus from Cape Town — 900 or so miles away — to buy his latest offering in person.

The conversation moves to Star Taxi Music, albums specifically made for, and christened in honour of, the minibuses many township residents still rely on for commutes, growing numbers of which had by that time begun installing serious sound systems. “Star Taxi Music had a lot of influence. Oskido set this up around 1993 or 1994,” says Positive K, name-checking one of the other artists who went on to set up Kalawa Jazmee with Christos. “He needed to choose tracks that would work for people travelling home in a taxi, giving tapes to the drivers to play.

The cassettes made money from adverts, and they would say the name of the tracks on the compilations so people listening would get to know the music, the artists. They would fight to get in the best taxis.”

While Apartheid was repealed in 1991, open elections were only held in South Africa for the first time three years later as segregation ended. Universities, or varsity campuses, now able to welcome students of different ethnicities, saw their Freshers Balls — which celebrated each year’s new intake and had already become key house music events — grow in significance as the demographics shifted. Positive K’s “first real gig”, at the Tshwane University of Technology in 1994, is a case in point. The smaller stage for Black artists reflected ongoing separation, which sadly can still be seen in the country’s society today. The fact that space quickly reached capacity with a diverse crowd — demand being far greater than the larger white music platform — proved Gauteng’s house pioneers were already stars in the making.

Fistaz Mixwell is also clear on how academic institutions pushed music to the masses. “You cannot separate South Africa from Apartheid. I was in high school when it ended, and in 1994 went to varsity — the first year there was no Apartheid and Black people were allowed in with white people,” Mixwell says, confirming he had started DJing by then, inspired by the likes of Christos. “I was starting a Civil Engineering course, and joined the [University of Johannesburg] radio station. I got there thinking there would be some vendetta against us as Black people, but realised a lot of white kids weren’t like that. They were our age, didn’t give a fuck about difference, and had been caught in a system created by their parents.

“At this time there was still no such thing as house music really, by name. We were used to the music we had locally, and anything outside that was just called international music. So there were guys that would take Adeva, Crystal Waters, music that was blowing up, and make local versions of those songs and play them back-to-back with the originals. We didn’t know it was called house, but over the next couple of years started introducing this to everyone.”

That task became easier when he was then offered a role as Music Manager at the national Metro FM, an opportunity he admits, through laughter, surprised even him. Along with stations such as 5FM, this would help turn underground house into a mainstream phenomenon, with Mixwell one of those taking a lead on playlisting and policy for 15 years, before leaving “to do his own thing”. Today, that’s running Matte Black, a plush restobar and music hangout built into the lower car park of a mall in Sandton, North Johannesburg, and — as he tells us out on the smoking terrace — a new 24-hour nightclub just around the corner, Insomnia.

On the balcony of The Living Room, an open-air rooftop music bar overlooking the thronging streets of Maboneng, a central Johannesburg district known for venues — which over the years included legendary deep house haunt 115 — another Johannesburg broadcasting institution comes up in conversation. YFM, we’re told in no uncertain terms, was also crucial to the explosion of house music.

It’s here we meet Soweto-born DJ Buhle. Hailing from South Africa’s largest township, itself home to around 1.3 million people, the Bezulu Records boss represents one of South Africa’s earliest female house DJs, and is clear on the impact Gauteng’s pioneers had on her, citing Da Vinci and DJ Bubbles — the latter a decade-spanning player renowned for pushing alternatives to house like tech, funk and electro — as major sources of personal inspiration.

“I remember talking to a lot of people [before I started out] who would say shit like ‘female DJs play strawberry music’. That means too soft, sweet, like disco... So I decided I wasn’t going to be one of those girls, but it was still difficult to get the recognition as a female, even playing harder tunes,” she says, telling us that deep 4/4 sounds first lured her in around 2000. “House was already dominating, but for a long time we didn’t have the resources, networks, infrastructure.

“People like Christos have done and grown so much, it’s easier for us now to do the business side of things, which is dope because it means you can be sustainable,” she continues. “There’s a gap that had to be bridged and an understanding that had to be reached. Today, the hatred here is less, but the problem now is infrastructure in the townships. I mean, we’ve had rain for the last two days and houses are flooding. What the fuck? But in terms of music, we have bridged the gap, we are there.”

"Some could say it was just music, but in 1994 there was still a need for Black people to hold on to each other; this music helped foster the camaraderie needed after such brutal oppression.” – Levi Love

Levi Love has similar thoughts. Now based in Manchester, UK, but raised in Sebokeng, a township 45 minutes south of Johannesburg, for the past five days the man behind the Mas O Menos and Bambanani labels has been DJ Mag’s fixer, finding routes to artists, our historic guide, drinking buddy, even organising a room for us in his childhood home. As we say goodbye he’s starting the process of transforming a small shack in the garden, built by his late father, into a studio for local kids. His ethics mirror so many we’ve spoken to, those he grew up around — a determination and desire to nurture creative potential at risk of being lost to inequalities.

“Positive K, Christos, and Vinny were the pioneers. This is when we started getting into stuff like Masters At Work, but also Mood II Swing, Quentin Harris, Mr V,” says Love. “When I moved to Pretoria to study from the township my life changed. I met Vinny in 1995, Positive K in 1996. And this is when I got heavily into music, seeing guys like Christos playing in Pretoria. And at the 60s Parties up in Mafikeng. I was there for the second, when it started to blossom, and I think I attended the next eight. I remember all three of those guys getting annoyed at this 18-year-old following them around, until we became friends. I mean, we’re not that dissimilar in age. But they were my elders when it comes to music.

“They represent such a big cultural movement. Some could say it was just music, but in 1994 there was still a need for Black people to hold on to each other, this music helped foster the camaraderie needed after such brutal oppression. I can’t say it in any other way. This was a movement, lifestyle, community, and these were the people spearheading that. And this has given rise to so many, from myself to Black Coffee. We survived emotionally and personally through this, and people have not forgotten. I mean, Vinny — someone should give him a lifetime achievement award.”