How DiY Sound System blazed a trail for the '90s free party movement

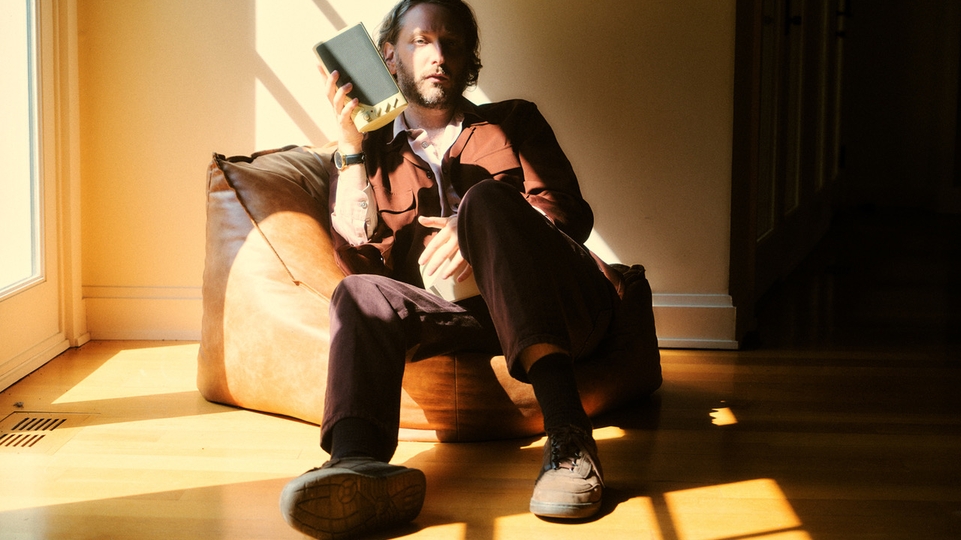

Throughout the ’90s, the DiY Sound System put on countless free events, ran a recording studio and two record labels, and took their hedonistic parties around the world. Here, Harold Heath speaks to co-founder Harry Harrison about his new book, Dreaming in Yellow: The Story of the DiY Sound System, and the collective's trailblazing legacy in the free party movement

The origins of DiY Sound System date back to a mid-‘80s England that was a very different place to how it is in 2022. In many ways it was an England that was freer than today: you could still squat properties, still claim the dole while learning to play an instrument or put on parties, and the country was still host to a teeming underground of free festivals.

However, the Conservative government had also brutally smashed the miners’ strike, embarked on a post-colonial war in the Falklands and overseen record unemployment levels, while Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher declared that “there’s no such thing as society”. It was into this harsh political context that DiY was born: a high-impact collision between the British radical, anti-establishment culture of squatters, anarcho-punks, travellers and free-partiers and the birth of UK acid house.

As we chat over Zoom, DiY co-founder Harry Harrison, now a genial, laidback father of two living in Wales, is full of brilliant stories and joie de vivre as he happily recalls his role in some of the most revolutionary events in recent British cultural history. “We were in the right place at the right time,” he says. “It was the end of the free festival scene, that last gasp of Stonehenge and anarcho-punk, when Glastonbury was lawless — the world was very different then. And I think we saw ourselves as promoting that lawlessness but using acid house as the perfect weapon.”

The free festival scene Harrison refers to has largely disappeared, but throughout the ‘80s there was a calendar of outdoor free events, mainly attended by so-called ‘new age’ travellers, hippies, punks, post-punks, ‘crusties’, squatters and others on the fringes of society. It was a fiercely anti-establishment subculture and one that Harrison and co. soon came into contact with via the Nottingham squat and house party scene.

“We hung out with a load of anarcho-punks and they were hardcore, serious poly-drug users,” he recalls. “They were messy as fuck, but they also organised loads of benefits for the miners. And we were into animal rights too, so we smashed a few butcher shop windows, went hunt-sabbing for a few years, all those kinds of anarcho-politics. Then we went to free festivals at 16, 17 and it just blew my mind.”

That punk ethos would feed directly into the character of DiY, creating a unique take on the rave template that put community, freedom and non-profit at the heart of what they did. “That’s why we were called DiY,” continues Harrison, “it’s a punk thing: it’s don’t listen, don’t vote, don’t take any shit, do it yourself, learn three chords and form a band, but instead of learn three chords it was buy some decks, get a soundsystem.”

Harrison became an enthusiastic attendee of the free party scene. “We went to a festival near Blackburn in probably ’83 and there was a chalk board that said ‘Line of speed 50p, Line of coke a quid, Mushrooms £2.50! We were like, ‘Wow, when does the music stop?’ and they were like, ‘It never stops, it goes from Friday to Tuesday’. Unfortunately, the music was a bit shit, it was Hawkwind and stuff, God bless them and all that but it wasn’t happening. But then acid house crossed with the free festival movement, that was where we were at and we were instrumental in it.”

“Everyone at our gigs got 75 quid with a 20 quid ‘nipper bonus’ if you had kids. Everyone got the same, the lighting guy, the sound guy, the DJs, and if they didn’t like it they could fuck off and go and DJ somewhere else. We had our major DJs but they all lugged the gear at the end of the night”

By the time Harrison, along with Pete ‘Woosh’ Birch (who sadly passed away in 2020), Richard ‘Digs’ Down and Simon DK formed the DiY collective in 1989, they’d already been into house music for a few years. “The one thing we had in Nottingham was DJ Graeme Park,” says Harrison, “who was playing house at the Garage from ‘87 onwards. We started going there every Saturday, that was my first experience of house music.” The DiY collective included engineers and sound crew as well as DJs, and they put together their own custom-built soundsystem and began putting on free parties.

DiY’s anti-establishment stance remained solid for as long as they functioned as a unit. While the mid-‘90s saw the rise of the superclub and the gradual encroachment of capital into dance music, DiY remained resolutely underground, alternative, and committed to an egalitarian vision of the disco, one that was reflected in how they dealt with money. “What I’m most proud of is that we were a collective,” says Harrison. “Everyone at our gigs got 75 quid with a 20 quid ‘nipper bonus’ if you had kids. Everyone got the same, the lighting guy, the sound guy, the DJs, and if they didn’t like it they could fuck off and go and DJ somewhere else. We had our major DJs but they all lugged the gear at the end of the night.”

DiY’s free parties began in summer 1990. They were mostly small affairs at first because, as Harrison recalls, most people on the free festival/ traveller scene still weren’t into house music at this point. Every weekend over winter 1990 the DiY crew were in the south-west of England, where the travellers were, putting on their free house music parties. Harrison remembers a particular event in the free festival calendar at Chipping Sodbury at the end of May 1991 as a major turning point. Up until then, soundsystems playing dance music were looked down upon by many of the traveller and crusty crew, but for the first time, the festival was all sound systems and no bands.

“It was getting bigger and bigger, you could feel it growing,” continues Harrison, “and instead of sound systems getting shit, being told to fuck off into the corner because ‘that’s not proper music’, suddenly there was this force of numbers, suddenly there were thousands of young people there.”

"The government were already a bit pissed off about raves, but Castlemorton really blew the gaff"

Momentum continued to grow over the winter of ’91 and then came the first big event of 1992: the Avon Free Festival at Castlemorton common. It’s difficult to imagine now, a five-day-long completely free festival/rave, attended by tens of thousands of party-goers, with the authorities powerless to act against it. An estimated 20-50,000 attendees — nobody seems able to agree on the numbers — turned up to the biggest illegal rave in UK history in the shadows of the Malvern Hills and partied over a very long weekend.

“The sun shone for the entire five days,” remembers Harrison, “I’ve never seen British weather like it. God was definitely on our side... And no one really organised it. There we no flyers, mobile phones, it just came together organically. You could never recreate it now, it was just unique, it was our generation’s Woodstock. We set up on the Thursday night and we didn’t finish till Tuesday.”

Castlemorton is an event that has since gone down in history, its ripples felt for years afterwards. It marked the beginning of the end of the ‘new age’ traveller lifestyle and of illegal outdoor raves via the Tories’ Criminal Justice Bill a couple of years later. As Harrison says, “The government were already a bit pissed off about raves, but Castlemorton really blew the gaff. That was May 1992 and at the Tory party conference in September, [senior Conservative] Michael Howard said he planned to introduce legislation to make things like raves illegal — and the Criminal Justice Act was made law in November ’94.”

DiY were unique among the soundsystems at Castlemorton in that they played deep house rather than the hard techno that was adopted by many other UK travelling sounds like Spiral Tribe. “Castlemorton was nine soundsystems and I went to all of them and the music was just a nightmare!” says Harrison. “It was just appalling, nosebleed techno, 160 beats per minute! As well as house, we played John Coltrane, Grandmaster Flash, Public Enemy. People came to our tent and stayed for two days, it saved their sanity. Because we really believed in the music. I guess we really believed in the ecstasy as well but you can’t really say that anymore... But there’s something sacred that happens when you get the right people, the right music, the right drugs in the right place — it just doesn’t get any better than that.”

“We did some properly mad shit that makes me shudder when I look back, it was so reckless and lawless... I look back now in my mid-fifties and just think, ‘Wow’”

Harrison’s role in the collective, after an aborted attempt at DJing (“I couldn’t be arsed: too difficult, too expensive, too serious!”) was as organiser, galvaniser and promoter. It’s an essential job in the success of every UK underground party: the facilitator, that one mate with a big personality who by default ends up putting on events, the larger-than-life member of your crew who makes things happen.

“I was the brains!” he laughs. “The gobshite! At the height of our fame around ’93, ’94 we had 13 or 14 DJs and my job was to herd the cats. I was the organiser. We were a collective but I also thought in a Stalinist way that if I don’t DJ I can kind of control things. I guess I was the strategist, the organiser, promoter, gobshite and money launderer!”

Because of their music policy, DiY were uniquely placed to take their free party ethos outside the traditional UK free festival circuit. As Harrison says, “We played Cafe Del Mar in Ibiza six weeks after Castlemorton, that was the unique thing about us. We were part of the Balearic scene, the crusty scene, the club scene, the soundsystem scene. There’s no way Spiral Tribe are going to play at Cafe Del Mar and there’s no way that Brandon Block is going to play at Castlemorton, so that was our unique selling point I guess.”

DiY also ran their successful club night Bounce for five years till the late ‘90s. They toured the country and built a network of Bounce events in major UK cities, their legal endeavours partly subsidising the illegal parties. They also took their events to places like Paris, Ibiza and Amsterdam, to Atlanta, San Francisco and Dallas in the US and to Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

And then there were the record labels. DiY put out a strong album in ’93 on Warp Records called ‘Strictly 4 Groovers’ before launching their Strictly 4 Groovers label in the same year. It ran till ’98 when it was replaced by DiY Discs. The Strictly 4 Groovers label featured beautiful mid-‘90s deep house like Crime’s ‘Rhythm Graffiti’ EP, To-Ka’s ‘Keep Pushing’ and ‘Good Together’ by Charles Webster and Pippa Jones as South Central, as well as music from members of DiY. DiY Discs continued in a similar vein with a series of deep releases from artists including Plej, Atjazz, Rhythm Plate, Stacey Kidd and Digs, Woosh and Mr Ski, building a reputation for high-quality underground house music.

However, nothing is static, certainly not in the wild world of clubbing, DJing and promoting. Over the last few years, the crew have met up and put on occasional events, making it all the way to their 25th and then 30th anniversary celebrations, but by the late ‘90s, Harrison says the DiY collective was “Fluctuating — there was quite a lot of addiction, quite a lot of mess, quite a lot of people moving, raising kids and so on...” Perhaps inevitably, real life had begun to infiltrate the dream world of the idealistic DiY. Gradually, parts of the collective moved on and went their separate ways.

Harrison originally wrote the first chapter of what became Dreaming in Yellow 20 years ago and was offered a publishing deal, but abandoned the project. “I’ve been waiting 20 years to write this,” he says. “I started it in ’98 when I had loads of time and no discipline. Then I had two kids and I had loads of discipline and no time.” He eventually finished it, fitting the writing around his job and family and it was speedily snapped up by Velocity Press.

“I just think it’s a fantastic story. We had some right scrapes, some outrageous behaviour, some truly moving moments: it’s just a fucking great story. DiY just never said no. It’s in the book but the core four of us, Digs and Woosh, Simon DK and myself, we did some properly mad shit that makes me shudder when I look back, it was so reckless and lawless. We smashed some police Range Rovers out of the way at a free festival in 1991... I look back now in my mid-fifties and just think, ‘Wow’.

It’s also a historically important story. I get emails every few months from sociology students who want to write about parties and protest in the ‘90s and need a quote. And I’ve not read anything yet that’s properly documented the sheer hedonism of the ‘90s.”

Looking back, now that the dust has well and truly settled on what Harrison refers to as “the intense battleground of the early ‘90s”, DiY’s legacy is perhaps clearer to see. They were a vital link between the traveller/‘crustie’ free parties and the wave of acid house hedonism that swept the country in the late ‘80s. DiY championed collectivism, celebrating the centrality of the group over the individual, pioneering a radically egalitarian approach to parties, where the power of music could change lives.

They set a standard, in terms of their music policy and the quality of their soundsystem but also in their not-for-profit approach — an approach that totally epitomised the very best of the UK house scene. “I meet people now and they say, ‘I came to one of your parties; it changed my life’. Still to this day. I think that’s our legacy,” says Harrison. “The music was vitally important; we thought we could change the world through house music and ecstasy. Maybe we did."

.jpg?itok=MzmStGqQ)