.jpg?itok=8dd59B7l)

How RP Boo’s footwork classic ‘Baby Come On’ changed Chicago dancefloors forever

When he sat down in 1997 to produce a track for the Chicago dance battles that he was DJing at, RP Boo had little thought of helping to forge a new genre of music. But the resulting track, the Ol’ Dirty Bastard–sampling ‘Baby Come On’, did more than challenge dancers — it helped bring footwork into existence

It’s never easy to pin down the moment that a new musical genre comes into being, to be able to say exactly when a long-gestating style warrants its own shelf in the record shops. At what point, for instance, did the music that Frankie Knuckles was playing at the Warehouse and Ron Hardy was spinning at the Music Box — a wide-ranging brew of boogie, disco, Italo material, synth-pop and whatever else would work the dancefloor — morph into the more narrowly-defined sound of what we now think of as house music?

Narratives of the sound’s evolution compete with one another; rival players vie for music-history glory. Eventually, opinion settles, to a degree, on an origin story: It’s accepted by most that house became the codified genre, house, in 1984, when Jesse Saunders released ‘On And On’.

It becomes even harder to pin down when you’re considering a hyperlocal and resolutely underground style like footwork. The short story is that the syncopated, sample-heavy and sometimes otherworldly sound — hovering between precision and abstraction at a heady pace of 155BPM and above — was honed in Chicago via an organic, dancer-led evolution that started with ghetto house, progressed through juke, finally becoming the rhythmically intense music that’s been soundtracking dance battles for three and a half decades.

Even that schematised history is up for grabs: Mike Paradinas of the UK label Planet Mu, who’s made a cottage industry out of spreading the footwork gospel since releasing the first ‘Bangs & Works’ compilation in 2010, once told Vice that “footwork is footwork, but juke can refer to footwork and ghetto house”. Whatever the case, many DJs and producers have played a role in the footwork story — but the consensus is that the first track that can truly be called footwork is ‘Baby Come On’, originally released in 1997 as a white label on Dance Mania and produced by a young dancer and DJ named Kavain Space, better known as RP Boo.

“They instantly noticed that the tracks I was playing were like nobody else’s. They were like, ‘You made that? Oh, you went to production now?’ Yes, I did!”

Paradinas and Planet Mu have a sub-specialty of releasing RP Boo material, both new and archival. The latest, the retrospective album ‘Legacy Vol. 2’, drops on 12th May. “His music is just so timeless,” Paradinas explains to DJ Mag. “It just gets better and better every time you hear it. I've been listening to a bit of it just while I was in the kitchen, going through a few of the old albums, and they just sound as fresh as when I first heard them.”

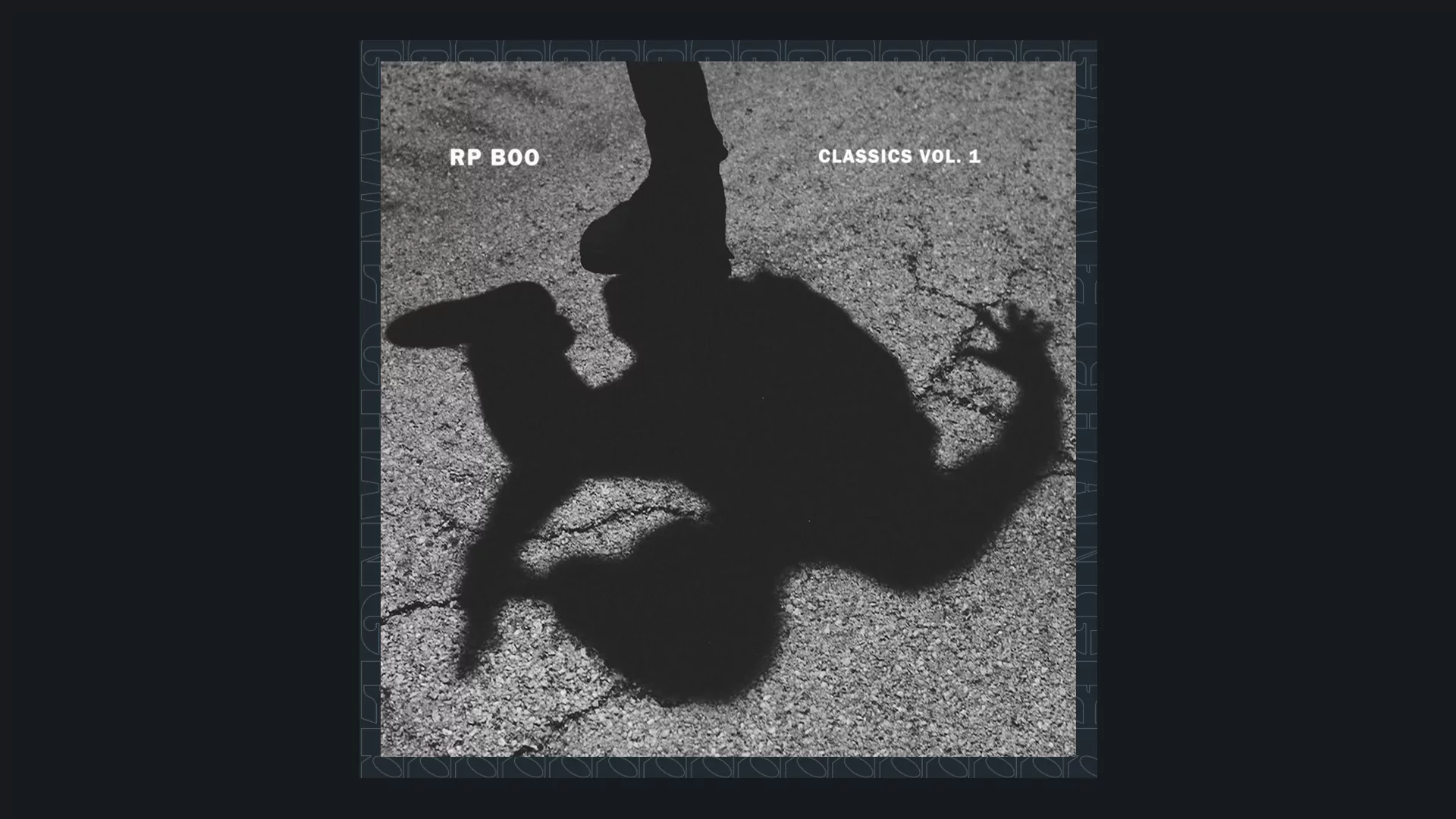

‘Baby Come On’ itself first came to the wider attention of the world beyond footwork dancers in 2015, through its appearance on Planet Mu’s ‘Classics Vol 1’. It might be a transformative track, but ‘Baby Come On’ is also an exercise in efficient simplicity. The track opens up with an almost traditional 116BPM funk intro, which makes what follows all the more bracing. Eight bars in, a 148BPM kick-drum, leisurely by modern standards, takes over, layered with a low-end bass throb.

Crisp handclaps hit on the one and two beats, later shifting to the two and four, while the stuttered vocal sample of the track’s title — courtesy of the 1995 Ol’ Dirty Bastard cut ‘Baby C’mon’ (also utilised to fine effect on the Bad Boy Fantasy version of Mariah Carey’s ‘Fantasy’) — is looped into infinity. That sample carries the workload when it comes to the tune’s syncopated feel, a defining ingredient of the footwork that followed.

It would be wrong to claim that Space alone truly invented footwork with ‘Baby Come On’: DJ Deeon, DJ Spinn, DJ Milton, DJ Clent, Traxman and the late DJ Rashad, just to name a few pioneers, all played roles. Paradinas, for example, cites DJ Clent’s 1998 track ‘3rd World’ as another of footwork’s foundational tracks: “That one brought this sort of half-speed clap thing, which is fundamental to footwork,” he says. But there’s no denying that in the incremental development of footwork, ‘Baby Come On’ is one of the biggest increments of all.

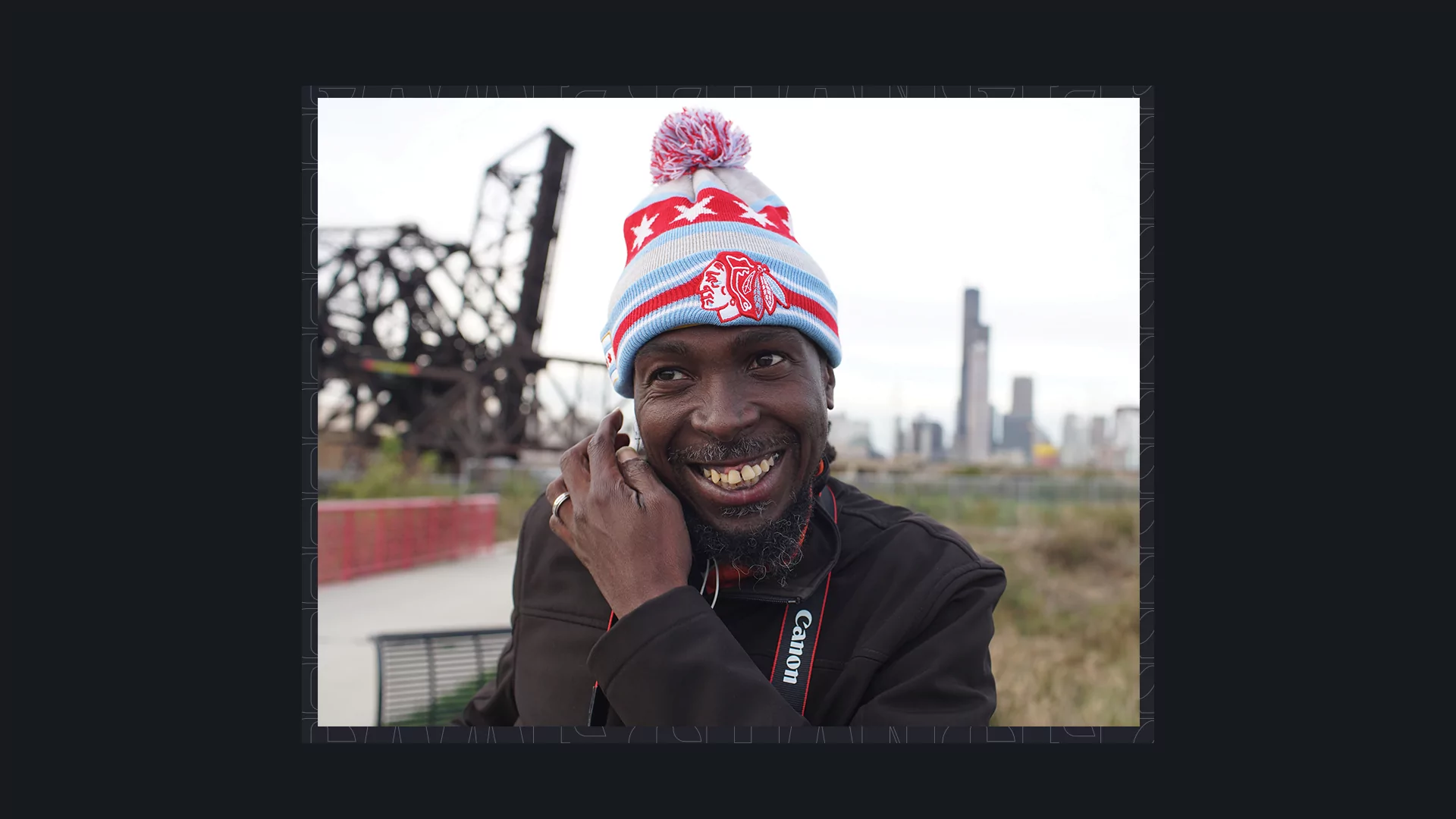

Paradinas mentions another impetus, other than Space’s music itself, for regularly returning to the RP Boo well. ‘He’s just so nice to deal with,” he says. He’s right. When DJ Mag catches up with Space via Zoom at his Chicago home, he’s ready with a smile and a warm greeting — which, considering it's early in the morning (by DJ standards at least) is saying something. “It’s okay! I’m always up early,” he says. “My wife, she works remote, and she's up sometimes at 4:30. And if she's up, I’m up, and we just have our coffee and I walked the neighbour's dog at 8 in the morning.” He spins his laptop around to show off his setup, which boasts a pair of Technics and zero CDJs. “That,” he exclaims with a big smile, “is why they call me Record Player Boo!”

Space is a third-generation music man; his grandfather “did work for Chess Records and had a couple of gospel groups”, while his father, who lived in Boston, played bass in a handful of bands. “But I didn't get to see all that because he was in Boston all the time,” he says. “I felt it, but I didn't know how deep the roots were 'til years later. I was like, ‘Oh, I see why I get the musical sensation of the purity of enjoyment from it. My father and grandfather, they were the backbone of my music lineage.”

Growing up in Westside Chicago in the ’80s, Space was already immersed in footwork’s earliest house music antecedents, listening intently to DJs like Farley ‘Jackmaster’ Funk and the rest of the Hot Mix 5 on WBMX. By the ’90s, he was dancing with the Mega Move crew, later joining up with the Southside crew House-O-Matic as a dancer and DJ. It was during his time with House-O-Matic that he figured he needed more music to challenge the dancers with — and who better to take on the chore of making that music than himself? Most published accounts credit DJ Slugo, who had been producing ghetto house and juke for Dance Mania, with teaching Space the ropes. According to Space, those accounts are off the mark.

“No, I learned by myself,” he says. “That’s why my sound and flow are the way it is.” But he does credit Slugo for turning him on to the Roland R-70 drum machine, a piece of gear that he relies on to this day. “DJ Slugo had one. I was like, ‘Where do you get that from?’ He said, ‘Guitar Center. Go there, they should have some more’. So that was it.” He sped down to the store and picked up the very last one. “No instruction manual. I didn't know how to even get started,” he laughs. “I was able to turn it on, and that was about it. I didn't know at that time how to copy and switch from bank pad one to two. So what I was doing, I was recreating the same steps that I had previously done, and then added on. It was so time- consuming, rebuilding from scratch again to the next pad, but I did that for a while.”

Eventually, it was DJ Deeon, who by that time already had a number of now-classic ghetto house tracks on Dance Mania, who explained the machine's finer points. “But I’ll never forget what I learned by learning on my own, so when it came time to producing my sound, that was going to be all original,” Space says. “I was just getting it how I wanted it to feel and sound on the drum machine.” By ’95, he was ready to play his own tunes at the battles, but still had a bit of nagging doubt about their worth.

“I was not to the point of actually being afraid,” he says. “It was more like, are people going to really like this? Because nobody knew that I had even gotten the drum machine! Nobody knew I was making music at all.” He ploughed ahead nonetheless. “And they instantly noticed that the tracks I was playing were like nobody else’s. They were like, ‘You made that? Oh, you went to production now?’ Yes, I did!”

By 1997, Space had added another key piece of gear to his arsenal. “I got a sampler, the Akai S01, from DJ Deeon,” he says. “That’s the same sampler that he based some of his biggest hits off of. I was like, what a blessing!” The unit wasn’t done with hit-making yet — it’s the sampler Space used to manipulate ODB’s gruff voice on ‘Baby Come On’.

“It wasn't called footwork yet. We just called them tracks, that’s all. But that track... it was just the way that I had the beat going, it was so rhythmatic that people loved dancing to it.”

“What I did was I had the ‘baby come on’ sample on a loop the whole time until I get to the mash-up part, then I did that manually with my fingers, and I was just recording it all the time,” he says. “So I was using two hands while recording on the four-track.” As Space says is the case for most of his tunes, the inspiration for ‘Baby Come On’ came from everyday life.

“I was out with a friend Friday or Saturday night,” he says. “He parked the car, and I’m there listening to the radio station B96. I don't know what DJ it was, but he’s playing [Mariah Carey’s] ‘Fantasy’, and it gets to ‘baby, baby come on, baby come on, baby come on’ — and when he got to ‘baby come on’, he kept beat-mashing it, and just kept looping it. You could hear that it was live. I was like, that's nice! At the time I didn’t have the sampler, but when I finally got the sampler, I'm like, wait a minute, maybe let me try to do what I heard. And I did it. I just put a beat behind it.”

The combination of that beat and that sample did exactly what it was supposed to — challenge the dancers. “It wasn't called footwork yet,” Space says. “We just called them tracks, that’s all. But that track... it was just the way that I had the beat going, it was so rhythmatic that people loved dancing to it. ‘Baby Come On’ did its job. It absolutely did its job.”

Space, at that point, was a constant presence on the local scene, dropping tracks and playing the battles — but global recognition was still years away. And one must pay the rent, so Space was still holding down a day job. “I was working at the spot on 59th and Western called Speedway Oil Change,” he says. “I started there in 1995.”

His co-workers were supportive of his nascent production career. “As a matter of fact, a lot of the inspiration for the tracks that were to come came from them,” Space explains. “After CD burners came about, I was able to go home, burn tracks, and I would say, ‘Here’s something I think you’re gonna like!’ And they’d laugh, because there would be something that we experienced, or something that they’d heard me say, but they wouldn’t know that I’d gone home and made a track about it. They’d be like, ‘You’re just a genius’.”

Space was still working at Speedway when ‘Bangs & Works Vol. 1’ came out in 2010 — its success, and that of the follow-up volume, enabled him to finally leave the job behind. Space didn’t put ‘Baby Come On’ together with the thought of building a legacy. He had zero thoughts regarding creating a tune that would contribute to the birth of a new genre. But he knew pretty quickly that the track was something special.

“I was not to the point of actually being afraid... It was more like, are people going to really like this? Because nobody knew that I had even gotten the drum machine! Nobody knew I was making music at all.”

“Not many tracks became very noticeable back then,” he says, “but one of the things I caught on to was that, right after I did it, that sample became the most used sample in tracks for a long time. They’d use ‘baby come on’ and just switch it up a little bit.” And I felt good about it, but what it did was make me go, ‘Oh, I’ve got a lot more to come!’”

The music Space is making today still feels revolutionary. Take a listen to his 2021 long-player, ‘Established!’; part of its appeal is the way it references the music of the past via samples of ’70s slow-jams, Paradise Garage classics and more, and squeezes them into a rhythmic template that still feels like it’s bending the space-time continuum to its will. It’s made for battles, but it has the feel of music that’s aiming for the heavens.

Still, on the eve of the release of ‘Legacy Vol. 2’, Space is grateful for the attention that his older material — including, of course, the groundbreaking ‘Baby Come On’ — still garners. And, he says, there’s more to come — he still has plenty of ‘Baby Come On’–era material that’s never seen the light of day beyond the battles.

“I still have all my cassette tapes, what I call the B-sides, that I recorded everything on, and my Tascam is still working,” he says. “I’m going to pull out those archives sometime. Some of those tracks were mind-blowing, especially how the samples were chopped up and how the beats were super strong... It’s crazy.” The world awaits.

(2).jpg?itok=vtMPIgMC)