It takes a village, people: preserving San Francisco's gay disco history

The flamboyant electronic sound of San Francisco’s dancefloors soundtracked gay liberation in the '70s and '80s, even as its community faced decimation as a result of the the AIDS crisis. Marke Bieschke takes a deep dive into the efforts being made to preserve ephemera of the city's pioneering scene, and speaks to the San Francisco Disco Preservation Society, Dark Entries' Josh Cheon and musicologist Louis Neibur about his comprehensive new book, Menergy: San Francisco’s Gay Disco Sound

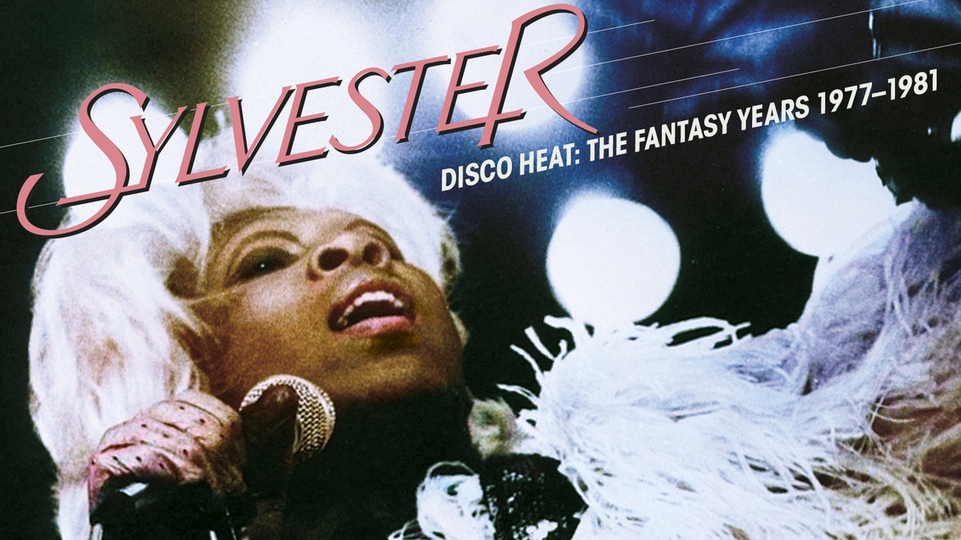

Deep in the vaults of the San Francisco GLBT Historical Society and Museum Archives, a modest wooden crate glows with the importance of a sacred reliquary. It contains the personal effects of Sylvester, the Black, gender-defying performer who started out as a countercultural star in the early 1970s and rose to become a global disco icon, before passing away from AIDS in 1988.

Items inside the crate, recently transferred from his estate into the archives’ professional hands, include his gold records, industry awards, concert flyers, photographs and newspaper clippings. Also secured for future generations of disco pilgrims are his hair-pins, brooches, earrings, sequinned stage costumes and, touchingly, a mounted collection of exquisite satin gloves, which of course the diva framed himself.

Sylvester’s effects are part of a growing disco collection at the archives. Dedicated preservationists have catalogued and stored LGBTQ community artefacts since 1985, when the Historical Society was formed to save the belongings of people killed by AIDS from the trash heap. Sylvester’s musical story frames a wild, liberating, eventually tragic but ultimately inspiring period in gay history; one which unfolded on San Francisco’s dancefloors, amid the ecstatic jangle of tambourines and the whoosh and clack of hand- painted fans. It changed the course of electronic dance music — then was wiped out by a deluge of death.

Can the sounds and spirit of this essential scene be captured, before they fade away forever? Joining the archives in the effort is a new book documenting the history of San Francisco disco called Menergy, an online archive of DJ sets from the San Francisco Disco Preservation Society, a steady stream of previously unavailable music released by the Dark Entries label and a host of faithfully retro parties. To save San Francisco disco, it takes a village, people.

In recent years, as DJs and dancers are more visibly celebrating the Black, queer roots of dance music, the outspoken, unabashedly gay Sylvester has risen to deity level — the falsetto-voiced Queen of Disco whose hits ‘You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real)’, ‘Dance (Disco Heat)’, and ‘Do You Wanna Funk?’ have powered the LGBTQ community through triumph and heartbreak, and testified to the connection between disco’s rapturous hedonism and the Black gospel music of Sylvester’s youth.

To many other listeners, disco has become a shimmering algorithm of sleek production and instantly recognisable hooks — endlessly sampled, retouched, remixed and edited to cast a beam of golden warmth on any party, wedding or household chore. Shorthand for naughty dancefloor decadence pleasantly repackaged as nostalgia, disco has managed to shed much of its corny reputation. But it’s still a sonic monolith, a brief streak of mirrorball joy before they put everyone in neckties or on the dole.

The actual story of disco, however, is more complex, beginning with the fascinating micro-diversity of its regional sounds and scenes. (Saturday Night Fever’s ultra-straight, Brooklyn Italian-American pick-up joints and Montreal’s quaintly experimental approach were just two variants.) That story also includes the way disco popularised inventions like mixing and beat-matching, technologically complex lighting and spatial sound design, 12-inch records and remixes; arguably, disco popularised electronic music itself.

Along with Sylvester, trailblazing producer Patrick Cowley, record company founders Marty Blecman and Johnny “Disco” Hedges and a slew of gay DJs were architects of the high-energy San Francisco disco sound, a delirious permutation that stoked 24-hour debauchery in the city’s dance palaces, bars, bathhouses and roiling street scene of the late ’70s and early ’80s. Despite the homophobic and racist US backlash of the infamous Disco Demolition Night of 1979 — which saw a pile of records from mostly Black artists detonated in Chicago’s Comiskey Park as a white mob chanted “Disco sucks!” — the party in San Francisco never stopped. In fact, it only got more gay.

Menergy: San Francisco’s Gay Disco Sound, published by Oxford University Press, is written by musicologist Louis Niebur. The book details the rise of disco in the city, starting with the influence of DJ Johnny “Disco” Hedges; first in 1973 at the Mind Shaft club, then later at the luxurious City Disco, which mixed in live performance for a cabaret-like atmosphere. It follows the sound’s progression through larger dance clubs such as Oil Can Harry’s, Alfie’s, Dreamland, the EndUp, the Rendezvous, the cavernous I-Beam and Galleria Design Center, and after-hours climax Trocadero Transfer — with plenty of back alley, bedroom and behind-the-booth intrigue along the way.

Homegrown tracks like ‘Menergy’, ‘Megatron Man’, ‘Cruisin’ The Streets’, ‘Disco Kicks’, ‘Lucky Tonight’, ‘Sex Dance’, ‘Backstreet Romance’, ‘Shot In The Night’, ‘Right On Target’, ‘Homosexuality’, and ‘I Wanna Take You Home’ stoked an almost never-ending party. Tens of thousands of men lived by the “four Ds”: disco, drugs, dish and dick.

The book also traces how local classic rock label Fantasy slowly turned its attentions towards disco in the early ’70s, growing into a leader of the sound and spawning gay-owned labels Moby Dick, Fusion and Megatone. We hear from classic DJs Lester Temple, Steve Fabus, Jon Randazzo, Bill Motley and essential Miami transplant Bobby Viteritti, and performers like early disco enthusiast Frank Loverde, Sylvester backup singers ‘Two Tons O’ Fun’ Martha Wash and Izora Rhodes of ‘It’s Raining Men’ fame, and the deliciously personable Lisa, whose ‘Jump Shout’ became an international club sensation.

Along the way, seminal moments in history unfold — the assassination of gay rights leader Harvey Milk and San Francisco Mayor George Moscone by a disgruntled conservative politician; protests and early triumphs of the gay liberation movement that brought thousands into the streets; the shock of AIDS that decimated the community, along with the galvanising rise of AIDS activism. There’s even a little civic infrastructure: what other city would open up a new subway station with a massive underground Metro Madness party, headlined by Sylvester himself in a flaming red sequined jacket, and complete with dimly lit carriages for “intimate activities”?

“Disco is so important to the gay movement, it was the first time we could dance together without being thrown in jail” — Louis Neibur

Go West, Young Men

“Disco is so important to the gay movement because it was the first time we could dance together without being thrown in jail,” Niebur said, pointing out one of the important effects of the 1969 Stonewall Uprising. That rebellion and riot against discriminatory police raids in New York City’s Greenwich Village, centred around the Stonewall Inn bar, helped kickstart the contemporary gay rights movement.

It also gave a boost of energy to ongoing legal battles, accompanied by queer community “sip-in” protests at hostile bars, which eventually ended bans on same-sex dancing around the US. “There were times back then where if you even swayed to the music, the bartender would yell at you because he didn’t want to get busted.”

Now that people could openly dance in bars, the music changed, welcoming upbeat sounds like dramatic, strings-drenched Philly soul and later Motown, Sly Stone’s raw funk and the soul of Bill Withers and Barry White. Musty jukeboxes were replaced by humans spinning the latest seven-inch singles and deeper album cuts. Stonewall also led thousands of queer people out of the closet and into the streets, bars and dance clubs of major cities, creating a public gay culture for the first time. A new culture needs a new soundtrack, and disco developed alongside this massive coming out.

San Francisco, deep in the throes (and some of the hangover) of its hippie revolution, quickly became a magnet for gay men eager to escape oppressive small-town environments and join in the dance — with extra helpings of sex. It was a lusty mass migration, abetted by countercultural permissiveness and cheap rents, as older San Franciscans moved out to the suburbs. The Castro, Polk Gulch and South of Market neighbourhoods glittered with bare chests and marquee lights. By the time disco superstars the Village People released their priapic anthems ‘Go West’ and ‘San Francisco’, the once-provincial burg was now the Emerald City on the Yellow Brick Road to gay Oz.

The movement came with a famous look — a macho, denim-clad, working-class aesthetic that gradually dropped its scruffy counterculture edginess for the sleek, moustachioed look of countless Freddie Mercurys. This was the “clone”, which simultaneously appeared in New York and San Francisco, home of the “Castro clone”. As historian Randy Schilts described it at the time, “The dress was decidedly butch, as if God had dropped these men naked and commanded them to wear only straight-legged Levi’s, plaid Pendleton shirts, and leather coats over hooded sweatshirts.”

As with all good cultural excavations, Menergy puts some of the utopian myths under the microscope. The clone look may have started as an empowering reaction against stereotypes of gay men as prancing, effete nellies. Yet it was also overwhelmingly conformist, marginalising alternative gender expressions. Sylvester revolted fabulously, declaring, “Fuck this. I must spend $60,000 a year on clothes, and I’m not going to reduce myself to 501s.”

The scene was also incredibly white and male — people who could more easily uproot their lives economically and socially — and Menergy highlights women and people of colour, like DJ Chrysler “Frieda Peoples” Sheldon, who was shut out of prominent positions and often asked for several forms of ID because he was Black. The endless partying, too, gets an unblinking eye: Niebur quotes one clone describing MDA, aka ecstasy. “We used to say it stood for ‘Must Dance All-night’. And the next day it stood for ‘Mustn’t Do it Again.’ Because you were totally wrecked.”

Hot Tales On The ‘Floor

Niebur, a professor at the University of Nevada in Reno, came to his subject through his work on film and television music. His first book detailed the history of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, which developed much early electronic music. He also adores the pop music of the late ’80s, much of it spawned by the gay Hi-NRG scene of London clubs like Heaven, which echoed and furthered the San Francisco disco sound after it faded in the US. “I’m mad that the UK gets all the credit for this music, but you can’t deny the power of a good Ian Levine or Stock Aiken Waterman production,” he says.

The through-line of all this was the invention of electronic dance music, which led him directly to Sylvester, Patrick Cowley and San Francisco disco. A night out at San Francisco’s retro-disco Go Bang! party cemented his resolve to document how the music and culture developed side-by-side. “Queer history always has to be reconstructed from ephemera, because until recently nobody’s really valued our history, or thought it was worth preserving,” he says. “There’s no Smithsonian Museum of Queer Culture. You have to search through the bar ads and event calendars in gay magazines, music reviews that are full of scene gossip, peoples’ diaries, rare photos and obituaries, because so many stories were told about the DJs and musicians that were dying of AIDS. And then interviewing people from back then, which is a race against time. A couple of my subjects died while I was writing the book.”

Niebur combed through decades of the Archives’ recently digitised community newspapers (including a database of the Bay Area Reporter’s more than 10,000 obituaries) for clues to the past. “But the primary documents are the recordings. The sounds and the lyrics that people wanted to hear at that time, what they wanted to dance to, tell so much of the story. There’s a lot of surprising evolution. Sometimes the music sounds like, ‘Wow, they really had no money when they made this’; or listening to Patrick Cowley, as he progressed over the years. There are the big hits, porn soundtracks... you can really hear the story there.”

Cowley, the precocious gear-head who started in the scene working the City Disco’s dazzling 16,000-bulb lightboard, basically invented San Francisco disco’s high-energy sound when he melded his love of gay sexual energy and countercultural ideals with emerging technology. He was among the first to enrol in San Francisco City College’s groundbreaking Electronic Music Lab classes in the early ’70s.

Matching blazing ambition with technical confidence, in 1977 he took the then-audacious step of creating a 16-minute, futuristic remix of Donna Summer’s ‘I Feel Love’ on his bedroom equipment, submitting it unsolicited to her record company in 1977, which it eventually released. Cowley’s music embraced the octave-hopping disco arpeggio descended from pioneering bass player Larry Graham and heard in hits like ‘Disco Inferno’, but pitched to a heart-racing gallop.

When Sylvester heard what Cowley was doing, he immediately tapped him to edge his blues-y tracks with electronic sizzle, leading to some of the era’s greatest hits. Despite his fierce productivity, Cowley was full of devilish humour. One of his biggest solo hits, ‘Menergy’ (published through his Masculine Music company) was created with friend Marty Blecman when they were both high — its ludicrous title was meant to goof on a sometimes too self-serious scene.

While Cowley dominated the beginning of the sound, producer Barry Beam — a punk soul entranced by synthesisers (and a rare straight man on the scene) — took it to campy new heights in the mid-’80s, with giddy co-productions that had no use for coy double entendres, like Corruption’s ‘Show Me Yours’ and 1983’s ‘Castro Boy’ by Danny Boy and the Serious Party Gods, a lispy parody of novelty hit ‘Valley Girl’, with lyrics like: “It’s not pretty being easy. Gag me with a cock. Faaaaaabulous!” Beam’s bright silliness and spacey new wave sounds provided acid- tongued levity as dancers realised AIDS was closing in, and no help was coming from a government that would rather see them dead.

Cowley himself was one of the first to die in 1982, at the age of 32, so early in the pandemic there was no official name for the disease. AIDS ramped up the music’s urgency even as it began to empty floors. “It’s important to remember that DJing as we know it was still something pretty new at the time,” Niebur said. Continuous mixing, beatmatching, extended mixes and the 12-inch dance single had been invented by DJs at New York’s early ’70s Greenwich Village bars and gay Fire Island resorts, and a circuit of gay DJs and dancers quickly formed to follow and spread the new techniques around the country.

“San Francisco gay DJs were taking the art in all kinds of directions with this music. There was someone like Steve Fabus, who specialised in ‘sleaze’, the morning music of the bathhouse or the dancefloor when the sun came up, and which was more about slowing things down into a steamy, soulful groove. And then there’s Bobby Viteritti, from the Trocadero Transfer, with peak-time sets that were practically all electronic and all the same beat, almost like something you would hear in a techno club today.” To listen to hundreds of sets like those, Niebur turned to an almost miraculous digital archive from lost dancefloors.

Feeling Mighty Reels

It’s alarming to discover that the only thing standing between many of the precious DJ mixes from that era and the silent void of annihilation is a food dehydrator. That’s one of the tools DJ Jim Hopkins uses to rescue old cassette tapes and reel-to-reels, recorded in classic disco DJ booths, from disintegration. As the founder of the San Francisco Disco Preservation Society, Hopkins has digitised and posted hundreds of reel-to-reel, cassette and VHS tape disco sets online, rescuing them from basements, garages and storage sheds around the US.

Hopkins started learning how to DJ in 1978 when he was 13 years old, after attending a disco in Roseland, California, and convincing his father to buy him two turntables and a mixer from the neighbourhood Radio Shack. Hopkins’ father also gifted him his own father’s reel-to-reel tape machine, launching a lifelong obsession. In the ’80s, Hopkins was living in Sacramento and spinning at gay bars — until too many requests for Madonna drove him to the more underground house-friendly San Francisco.

In 2009, feeling nostalgic, he bought a reel-to-reel machine and went looking for blank tapes on Craigslist. There he found the daughter of DJ Michael Lee looking to digitise his collection — she had more than 60 of his recorded live sets, passed down when he died of AIDS in the ’90s. Sensing a new line of business, Hopkins worked out an arrangement where he could keep the tapes after converting them and post the mixes; the first, a 1975 Lee set from Bones bar.

From this, the Disco Preservation Society was born: first as a Facebook page, where it took off like a flaming rocket, and then as a full-fledged website. Right away, promoter and Trocadero Transfer soundsystem designer Rod Roderick, whose wild private blowouts at his “mansion” and various warehouses had helped usher in the city’s all-night mega-party scene, gifted him more than 480 tapes. “From there it just snowballed,” he says with a laugh. “Tapes began to take over my apartment.”

Hopkins had to invent his own system of preservation, digitisation and remastering, a complex process involving a T-shirt soaked in alcohol, old RX7 audio rescue software, and, yes, several hours in a food dehydrator, to eliminate mould and remedy deteriorating effects like “sticky-shed syndrome”. Other challenges include length (DJ sets were often six to nine hours), wildly varying track volumes and the sheer number of submissions from DJs, as they retire to Palm Springs or Florida and want to clean house.

“Sometimes they just arrive in my postal box like mystery Christmas presents,” he says, summoning images of white-bearded disco St. Nicks, downing piña coladas by a sparkling pool and sending off their legacies.

“There’s a real hunger for this music and for that time of celebration. Young and, well, more experienced dancers want that lush sound of music produced in a studio with full orchestras combined with the excitement of the electronics. It just feels human.” - Steve Fabus

Another disco spelunker, Josh Cheon of San Francisco label Dark Entries Records, has climbed through attic crawl spaces and delved into damp basements to discover Patrick Crowley’s prolific output — the unusually moody porn soundtracks, psychedelic electronic experiments and ravenously explicit sex diaries — much of which his label has released. His obsession with Cowley began when Johnny “Disco” Hedges announced that he was retiring to Palm Springs and was giving away all his records — an especially rich trove, as he had founded the Bay Area Disco Deejay Association record- sharing pool.

“There were two unmarked boxes of tapes in there that were a mystery,” Cheon tells us. “Even Johnny was like, ‘Don’t bother with those’. But they turned out to be these amazing unreleased recordings by Patrick. I knew the world needed to hear them, as part of our history.”

Cheon, too, has been racing against time — George Horn, the Fantasy Studios engineer who mastered thousands of records, including those of Patrick Cowley and Dark Entries, recently died of Covid-19. Energised by their new cache of Hedges’ records, Cheon and his then-crew Honey Soundsystem requisitioned a former bathhouse space and threw a retro-disco party called Dancer From The Dance, after a classic gay novel from the period. (Cheon’s set from the party contained all the records mentioned in the book.) The rapturous response set Cheon on a course to release Cowley’s material over the next decade, as Honey continued to throw era-themed parties that summoned the past.

Honey was not the only party reactivating the menergy. The Trocadero Transfer staff held annual Remember The Party events through the ’00s, while the monthly outdoor Flagging In The Park event celebrates the dancefloor art of flagging and fan-dancing, its participants whirling through the AIDS Memorial Grove like neon butterflies. The monthly Go Bang! party combines creator DJ Sergio Fedasz’s youthful love of the genre with veteran DJ Steve Fabus’ four decades of disco experience. It isn’t unusual to see walkers and canes raised towards the ceiling there.

Outside of the city, parties like London’s Horse Meat Disco, Pittsburgh’s Honcho, Detroit’s Macho and more joined the call this past decade, to rediscover a joyous gay aesthetic that was overshadowed by AIDS trauma. “There’s a real hunger for this music and for that time of celebration,” says Fabus. “Young and, well, more experienced dancers want that lush sound of music produced in a studio with full orchestras combined with the excitement of the electronics. It just feels human.”

The grand-daddy of all San Francisco disco revival parties is The Tubesteak Connection. Each week since 2004 (though currently paused due to the pandemic), DJ Bus Station John has meticulously decorated tiny, ancient dive bar Aunt Charlie’s with handmade collages of vintage porn and party ads, promising “only music from 1975-1983” and recreating the man-to-man aura of yesteryear.

For him and others, the revival is equally about honouring musical forebears — Bus Station John’s records are mostly from collections of those who’ve passed on, their names and original notes inscribed on the labels and sleeves — and recapturing a lost immediacy, the physical human connection once ubiquitous before online hookups and cruising apps.

“The fact is, a great many gay men still want to find tricks and lovers, friends and boyfriends, live in-the-flesh — the good old-fashioned way — in a space created specifically with that desire in mind,” he says. “I’m not sure we or any other club will ever be quite as colourfully freaky as we used to be, since the demographics of San Francisco have changed so dramatically. What was once ‘Gay Mecca’ has become financially inhospitable to the new generations of young queens. And, heartbreakingly, so many others have had to leave. The good news is there are still enough interesting people here to make for a lively party.”

Dancing Into The Stars

When the San Francisco gay scene was at its peak, there were more than 100 bars, bathhouses, sex clubs, cabarets and discos — now, the city is down to about 20. As Niebur tracked the nightlife establishments and movements of San Francisco’s disco players in the ’70s, a kind of ghost map sprang up of a scene long-erased first by AIDS, then by gentrification and assimilation. “Being able to retrace everyone’s movements really brought the non-stop energy back to life,” he says. “It also brought home how much is gone.”

Menergy tells of people bravely trying to keep the music alive when DJs, club owners, record executives and party promoters were struck down. Miraculously, the San Francisco scene did live on, as house music took over as the soundtrack of LGBTQ activism, and more trans people and people of colour joined the dancefloor.

If there was a true “grand finale” to the San Francisco disco scene, it took place one night in 1988, as DJ Steve Fabus took to the decks at Dreamland, the classic disco which had reopened in a burst of glittering optimism that the scene would revive. “It was a wonderful night because all these people were coming out to hear this new house music, and I was playing to a packed floor at 10pm,” Fabus recalled. “Suddenly the promoter Ron Baer came in the booth and said, ‘Honey, Sylvester’s here’; this was a big surprise, because we all knew he wasn’t doing well. The last time we’d seen him was leading the Gay Pride parade in a wheelchair, looking very stricken. But of course fabulous — it was Sylvester!

“The club had two levels, and the DJ booth was on the bottom, so they rolled him on top of the booth, directly over me,” he remembers. “I turned on the mic and made the announcement, ‘Everybody, Sylvester is here to say hello’. The response was like thunder. People just started clapping and stomping their feet so much the booth shook. I had to think fast. So I cued up all my Sylvester songs and made a medley. The club was going wild.

“After about 45 minutes Ron said, ‘Sylvester is going to leave’. I stopped the set. Sylvester spoke and said, simply, ‘Thank you so much. Goodbye’, and was wheeled away. People were sobbing, stamping, screaming. Everybody was crying, I was crying. It hit everybody that this was his goodbye. He has said goodbye. This went on for five minutes, six minutes, seven minutes; shouting, ‘We love you’. Nothing more could go on after that. I got on the microphone and said, ‘Good night, take care everyone, I love you’. And people just slowly left the club, until it was empty.”

Louis Niebur’s Menergy: San Francisco’s Gay Disco Sound is published by Oxford University Press in January 2022. Pre-order it here.

The San Francisco Disco Preservation Society digital archive can be found here.