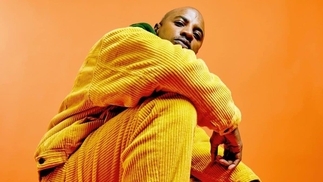

Recognise: DJ Lag

Recognise is DJ Mag’s monthly mix series, introducing artists we love that are bursting onto the global electronic music scene. This month, we speak to DJ Lag, Durban’s self-proclaimed “gqom king”, about the future and history the sound...

DJ Lag is a pioneer of one of the most exciting electronic music movements to surface this decade. Over the last few years, gqom has steadily infiltrated soundsystems across South Africa, through music from the Durban-based producer alongside contemporaries like Rudeboyz, Emo Kid, Dominowe, Distruction Boyz, Julz Da Deejay, Naked Boyz, TLC Fam, Griffit Vigo and many more. Stemming from the the city’s townships, the sound has shifted from an underground DIY scene to becoming a prominent feature in South Africa’s charts. And it’s not just big in the country it was born, with Europe-based DJs that exist on the bleeding edge of electronic music championing the sound, including Kode9 — whose Ø party hosted DJ Lag last July — Shannen SP, Ehua and more all adopting it into their sets.

“When I started I wasn’t expecting this,” DJ Lag, real name Lwazi Asanda Gwala, tells DJ Mag over Skype from Durban. “I thought gqom was just going to be for South Africa, but then it became huge. I’m really proud to see how the sound grew over the last few years. Every time I perform and every time I go round the world, people go crazy.”

This year has already seen Gwala spin at Berghain, as well as clubs in Turkey and Sweden, whilst his International Pantsula tour makes stops in Denmark, France and, of course, South Africa. His Gqom Is The Present tour at the end of last year also saw him travel to the US, Canada and Australia, certifying that gqom has gone global. “Last year, gqom producers kept saying, ‘gqom is the future’,” he explains. “That was a big hashtag that was happening in South Africa. When I started the tour I felt like gqom is the present,” he smiles.

Starting as a micro-scene in Durban, gqom is personified by the dark, tense and hypnotic music found on DJ Lag tracks like ‘Ice Drop’ and ‘Khonkolo’, with the hard-hitting percussive sound’s name translating from Zulu as hit or drum.

“When gqom came it was made for clubs. Made for nightlife. Dance is the best thing in Durban, so when gqom came, everybody went crazy as it was the perfect combination. That’s why it took over”

“2012 was the year it got super popular in Durban,” Gwala explains. “But it was underrated. At the time the sound was raw. We didn’t know how to master our music. It wasn’t being played on radio or TV. We didn’t get interviews. Nothing. The big artists were trying to stop the sound being big. But, eventually, people started to love what we were doing and they couldn’t stop it. Now it’s the biggest genre in South Africa.”

Using a heady blend of hip-hop samples, chopped and skewed samples of African chants, Maskandi drums — a form of Zulu folk music prominent in South African townships — and broken beats, as it made its way out of South Africa, gqom created a buzz akin to dubstep and footwork when they first surfaced. It also utilises more familiar sounds found across house and techno, but to label gqom under another genre cheapens its ability to stand alone as a sound; one that was given the chance to fully develop as a youth culture away from the world’s gaze in Durban.

Before it boomed, kwaito was the biggest sound in South Africa, and gqom was a kick against its brighter, lighter tones by young producers more focused on the country’s vibrant party scene. “Kwaito is like pop,” Gwala smiles. “It was huge. But when gqom came it was something made for clubs. Made for nightlife. Dance is the best thing in Durban, so when gqom came, everybody went crazy, like, ‘What is this?’ It was the perfect combination with dancing. That’s why it took over.”

A central figure to breaking the sound out of South Africa, Gwala started producing when he was still in high school. His mother fell in love with a man that ran an internet cafe in Claremont — the township Gwala grew up in — and after teaching him the basics in 2007, he gifted the young aspiring producer a copy of Fruity Loops so that he could start making his own music. “I got lucky to know the guy that was dating my mother,” he explains. “He bought me a computer and everything. It’s quite a rough neighbourhood to live in, as there’s a lot of crime happening there, but I was not focusing on what was happening in Claremont. I would just always be at the computer. I was that guy,” he laughs.

Gwala describes London as the second home of gqom due to the prominence of artists like Moleskin, the producer and founder of the Goon Club Allstars label, which has been pushing Durban sounds since it released Rudeboyz’s self-titled EP in 2015. He adds that its popularity outside of South Africa — also spurred by the Italian label Gqom Oh! — has played a large part in giving it more credibility in his home country. “I didn’t know how the sound makes the world go crazy until I started touring,” he says of gqom’s global impact. “When I started it wasn’t something that I had in mind.”

But before becoming a global phenomenon, gqom spent years as a DIY scene made by bedroom producers in Durban’s townships and played at house parties and bang houses — empty houses used for parties — in the city, whilst most of its originators were still in their teens. “The club scene wasn’t that good at the time,” Gwala recalls. “But we had a lot of house parties. There was a huge one that happened [every year] in Kloof when all the high schools closed and everyone was going away for holidays. All the schools in Durban would meet at that house party just to listen to gqom. That’s where it got popular. They were crazy. Man, I miss that experience.”

As gqom established itself as the sound of Durban’s youth, the city’s taxi drivers began to play a huge role in disseminating the music as it got bigger. Taxis in the city are often kitted out with huge soundsystems and lighting in order to attract customers, and drivers began vying to have the latest gqom productions. “People rent those taxis because they have super huge soundsystems,” Gwala explains. “If you have the best soundsystem and really nice new gqom, you’ll get a lot of customers. So as producers, we would make music and send it to the taxi drivers.”

The taxis would also park up outside the house parties, “They were full inside, full outside,” Gwala explains, whilst later the taxis would often provide tertiary soundsystems as parties started taking place outside in parking lots. As the sound grew, spaces like Club 101, Spank and Havana became hugely supportive. “Around 2014 we started having strictly gqom clubs,” Gwala explains. “That’s where the house party lifestyle died.”

Despite the staggering amount of DJ Lag material there is, Gwala’s Discogs page lists just two releases, as they are the only to be officially released by a label. One of his biggest EPs, ‘Trip to New York’, was exclusively released on WhatsApp, another medium key in the rise of gqom. We we used it to push our music because at that time we didn’t know about websites where we could upload music to download it,” he explains. “We’d just have WhatsApp groups and that’s where we shared our music.” And it was a masterstroke by the young producers in gqom’s early days, considering there were 162 mobile subscriptions per 100 people in South Africa in 2017 against three fixed broadband subscriptions per 100 people.

“I’m happy to see people from around the world trying to be a part of gqom as it’s going to create a big growth for the sound”

Gqom can now be heard across South Africa’s TV and radio, with superstars like Okmalumkoolkat, Cassper Nyovest, Big Nuz and Babes Wodumo — the latter’s ‘Wololo’ racked up almost 10 millions hits on YouTube — adopting the sound into their music. Gwali has recently been in the studio with M.I.A., with the pair currently working on music together, as well as starring on Kelela’s Warp released remix album, ‘Take Me Apart’. That’s all ahead of his debut at Sónar this summer and an upcoming collaboration with Hyperdub.

Gqom’s popularity has lead to scenes starting to pop up all over South Africa too, whilst the sound has started to fragment into different styles. Gwali refers to the hard, hypnotic gqom that he plays and was adopted in London as khonkolo, whilst sguhubhu is a more commercial sound that usually features MCs, and taxi kick — a sound built on particularly bone-rattling kicks and drums — is specifically designed for Durban’s taxis.

Tracks like Emo Kid’s ‘Futuristic Gqom’ and Gwali’s ‘Trip to New York’ also implement more melodious experimentation outside of the percussive element, a sign of how the producers are continuing to mature as musicians. He also recently worked with Epic B — one of the originators of Flex Dance Music in Brooklyn — on ‘Going Modd’, which landed at the end of last year, and he says crossing gqom with other genres is very exciting for the future of the sound. Gwali’s Twitter page is littered with snippets of future productions that look set to take the gqom forward. But is he worried about what gqom’s boom could mean for the sound?

“I’m not worried” he enthuses. “I’m happy to see people from around the world trying to be a part of [it]. I saw a guy in New York who was producing serious gqom like he’s from Durban,” he smiles. “I’m really glad that’s happening as it’s going to create a big growth for the sound.”

DJ Lag’s Recognise mix demonstrates exactly where gqom is at in 2019, featuring a number of unreleased and hard-to-find tracks from the producer. Listen to it below and buy DJ Lag’s ‘Stampit’ EP here.