The rise, fall and revival of UK dubplate culture

Born from sound system culture, dubplates were once at the heart of UK dance music: specially cut, exclusive records drove the evolution of genres from jungle to dubstep and grime. Here, Joe Roberts looks at the history of UK dubplate culture

This feature is part of our Record Store Day content series. You can also read our feature where 10 DJs select their most treasured dubplates, and also find out how to survive as a record store in 2023

My accountant called me one day and said, ‘You’re going to have to slow down your music purchasing’,” recalls Fabio, one half of drum & bass pioneers Fabio & Grooverider. It was the peak of the duo’s weekly Radio 1 residency in the early 2000s and they were cutting two hours of fresh dubplates each week. “‘The amount you’re spending, you could have bought a million pound house’,” he says, still a little incredulous. “I didn’t realise, but I was spending two and a half to three grand each month to make sure we had all brand-new shit.”

Born out of Jamaican sound system culture, and imported to the UK by the likes of legendary sound system Sir Coxsone Sound, the dubplate became the backbone of UK dance culture. An integral part of reggae, jungle/drum & bass, UK garage, grime and dubstep, cutting houses where dubplates were produced — such as JTS, Music House and Transition — fostered musical communities, cross-pollinating scenes and driving innovation through competition and collaboration. As the digital era removed the need for a physical medium, dubplates largely faded back to their sound system roots. But their spirit continued.

And with the advent of lathe cuts in the 2000s, which use plastic discs instead of the traditional acetate, a new generation is utilising them. “They’re exclusives,” explains Channel One selector Mikey Dread, who’s been cutting dubplates since 1980, of how acetate discs were used to make special tracks for select DJs. “Only you and one or two other sounds have it.” This could be an instrumental, but dubplate specials were tracks featuring vocals specifically about a sound system, a secret weapon when engaging in a soundclash. Continuing to cut dubs “up to this week”, Mikey says they’re an integral part of Channel One’s analogue sound. “Moving with the times doesn’t always make a sound system sound better. You go with what you know.”

“That’s how the scene moved at such a rapid rate. You hear something different and you’re like,‘What the fuck? I’ve got to come with something badder than that’” — Fabio

While Channel One have used various cutting houses — studios with the equipment and expertise to cut onto acetate (actually an aluminium disc coated with nitrocellulose lacquer) — a constant has been Music House. Located in Tottenham Hale, North London after previously being on Holloway Road, it’s a place steeped in history, turning out dubplates since 1985. When long-time cutting engineer Leon Chue passed away in 2020, heartfelt condolences online gave some sense of his huge influence, while a video from Reinforced’s DJ Tee Bone gave a glimpse of him at the controls.

“It was like a youth club,” says Fabio, describing Music House’s roots as the go-to for sound systems morphed into it becoming the centre of the nascent jungle scene, his generation’s “modern take on ’70s and ’80s reggae”. With no booking system, DJs rubbed shoulders as they waited for their cuts — provided to them by producers on DAT. “You’d walk in and see Randall, Frost, Kenny Ken, DJ Rap, Mickey Finn, Ed Rush, everyone was in there.” But there was also a clear pecking order. “No matter who was there, Grooverider would get his dubs cut first,” says Fabio, adding David Rodigan trumped everyone, thanks to being one of Music House’s longest running and most prolific customers.

“That was our social media, face to face,” says DJ Storm, who recalls how you’d hear a tune you wanted and try to work out who to speak to to get a copy. Sometimes you could get one there and then. Other producers, such as Goldie, says Fabio, made it clear their tracks were only for whoever they’d given them to. But the process of making a dubplate, which involves playing the track as it’s cut, meant everyone heard everything. “That’s how the scene moved at such a rapid rate,” explains Fabio. “You hear something different and you’re like, ‘What the fuck? I’ve got to come with something badder than that’.” Artists such as Photek, Dillinja and Source Direct were pushing each other to greater technical heights. “You could hear the standard improving literally week to week.”

If Music House was the centre of jungle, d&b and, later, grime, Transition in Forest Hill served the dubstep scene, thanks to its placement in South London. With a more formal booking system, it had a different culture. “If I was playing at DMZ, I’d probably go to cut four or five plates for the weekend,” says Plastician, adding he might see other DJs there. “Everyone was a bit secretive, as the big reveal for new tunes was DMZ. Nobody would really let you hear what they were cutting. People didn’t barge in to ask for a copy.”

“I had a very emotional attachment to dubplates. Even the smell, opening up a bag of them, brings back very strong feelings” — Youngsta

At FWD>>, where dubstep emerged, new sounds were being road-tested. While digital technology was arriving, music on CDs could be easily copied, explains Plastician, with unreleased tracks ending up on LimeWire or being passed around on MSN Messenger. So some producers such as Youngstar, who made ‘Pulse X’, would only share tracks on dubplate.

Fabio remembers the moment the dubplate dream ended, sometime in the late ’00s. By that time he was using a high-end cutting house, which worked with the likes of George Michael by day, and by night did drum & bass dubplates. DJing at Swerve one night, he went there with a Photek track. “I took a cab, which cost £25, then cut the dub, which by then had gone up to £65. Then I took a cab to the West End. The whole thing cost £110, so I was already thinking, this is getting really expensive,” with earnings already affected by the decline of vinyl sales. “But I thought, I'm going to kill it tonight.” When he got to the club, the warm-up DJ was playing the same track off a CD.

Dubplate’s ideal of exclusivity never faded, though. Big Ang says bassline’s heyday was when DJs mostly used CDs. But she keeps unreleased versions, such as a remix of ‘Walk On By’, because “the impact it has gives me a buzz when I play it in a club”. Marcus Nasty, meanwhile, has hundreds of digital dubplate specials that namecheck him, picking out Funky Twinz’ ‘Smile’ featuring Angel J as a personal favourite. “In funky I was really popular, so I think people thought if they sent me a dubplate, I’d play it. It worked! But I never really asked for them.”

Fabio doesn’t miss the expense, while Storm recounts taking heavy bags abroad in overhead lockers. Youngsta, an integral part of FWD>>, adds there are plenty of technical things you can do on CDJs that you can’t on Technics. But for all there’s a sense of having lived through a very special time. “I had a very emotional attachment to dubplates,” says Youngsta. “Even the smell, opening up a bag of them, brings back very strong feelings.”

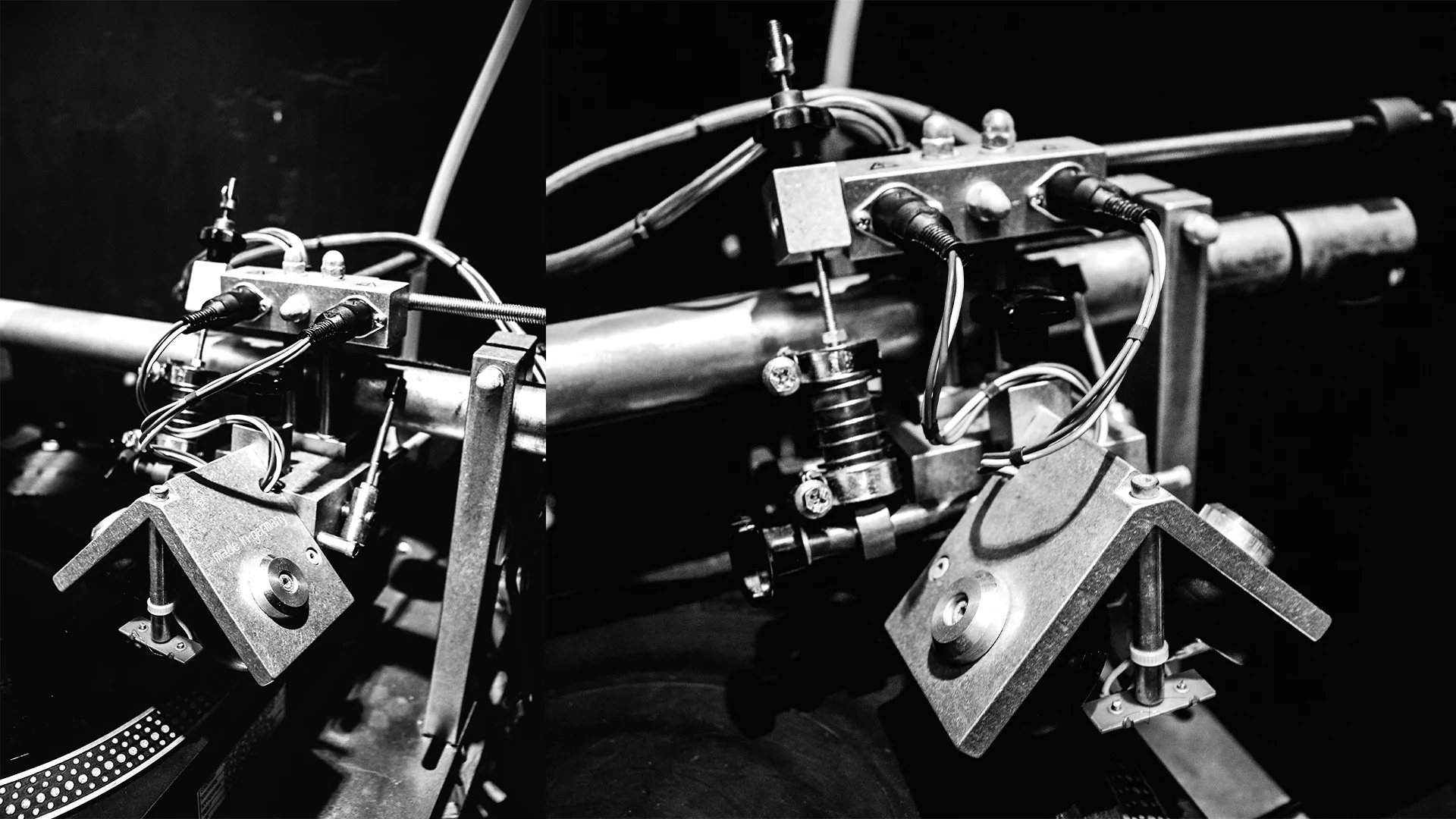

Perhaps this is why, despite the convenience of digital, a new chapter is being written in the history of dubplate culture. Club Glow DJ and producer Borai worked for a decade at Bristol cutting house Dub Studio, which after serving both the local scene and an international clientele is currently on hiatus. He explains how a German named Souri (Ulrich Sourisseau) developed a new way of cutting dubplates, inventing and selling a lathe that sits on top of an adapted Technics turntable and cuts into a plastic blank, the exact composition of which is a secret.

“Ultimately, the acetate is always going to have the best quality sound,” he explains. “The medium that you’re cutting into is soft enough to knock off some of the highs and adds this incredible warm bass. But it will wear out eventually.” This new generation of dubplates, he says, has a similar durability to vinyl, which means thousands of plays. This, combined with labels and producers looking for new revenue streams during lockdown, led to the phenomenon of limited runs of dubs — often sold via Bandcamp.

Starting 1-800-DUBPLATE with one of these lathes, DJ/producer Dexta has since built Planet Wax, a South London record shop, bar and venue, around it. “I yearn for human connection,” he says, on forging a physical space where DJs and producers congregate. He and business partner Sicknote come from the drum & bass scene, and he believes it’s important to remember the culture the UK scene is built on. “Buy records from your mates or the artists you like,” he says. “Get your tunes cut onto dubplate and give them to DJs who play vinyl, rather than sending them an MP3.”

It’s a new era, making it easier than ever to get a dubplate cut. There’s even a home vinyl recorder on the way. For some, though, there’s no straying from the original sound of acetate. “To me, they’re the genuine article,” says Mikey.