Urban Tribe's 'The Collapse Of Modern Culture' is an under-the-radar masterpiece of Detroit futurism

Urban Tribe, aka Sherard Ingram (DJ Stingray 313), released 'The Collapse Of Modern Culture' in 1998. Enlisting a host of Motor City legends and stepping outside the restraints of tempo and genre, Ingram created a slice of future-proof ambience. Here, Jack Anderson explores the largely under-the-radar LP

Released in 1998, Urban Tribe’s ‘The Collapse Of Modern Culture’ stepped outside of tempo and genre. A communal work helmed by Sherard Ingram (aka DJ Stingray), in which patience and empathetic listening are rewarded, the album’s chroniclers are Motor City bards: Anthony Shakir, Kenny Dixon Jr., and Carl Craig all show up as collaborators. Ingram and his Detroit buddies performed meditation on consumerist melancholy at the end of the millennium. Didn’t get the memo? Neither did most.

Even when it was new, the sheer strangeness of ‘The Collapse Of Modern Culture’ was too unusual a proposition for mass audiences. On the face of it, the coming together of such Detroit artists should really have made a bigger splash. A synthesis of downtempo Detroit and Warp stylings — the snapping grooves of Boards of Canada and Autechre are present — Urban Tribe’s epochal work was a gentle howl at the moon, unseen and overlooked.

Choosing it as one of the best IDM albums of all time, Philip Sherburne, writing in Pitchfork, hits this anomalous nail on the head: “It seemed too slow to be techno, too broken to be hip-hop, too electronic and vocal-free for most to recognise it as soul music... The mood throughout is melancholy and elegiac, with lyrical synthesisers poking through rumbling percussion like green saplings pushing through the rubble of a dead city.” And so, along with the majority of the long-defunct Mo’ Wax back catalog, ‘The Collapse Of Modern Culture’ never found its way to streaming services, meaning it remains a sumptuous slab of anachronistic music relegated to the annals of Discogs mythos and rarities bins.

Urban Tribe first came to life in 1990, with ‘Covert Action’ arriving on the seminal Detroit compilation ‘Equinox Chapter One’. The collective gradually evolved throughout the ’90s, in a tight-knit community where there were no airs and graces when it came to fostering talent. In an interview with The Wire, Ingram spoke about having Shakir, Craig, Rick Wilhite, and Dixon around, all offering help and guidance; while the concept was Ingram’s creation, it evolved cooperatively. He was humbled by the “valuable, invaluable assistance… Not only in encouragement and technical advice, but actual hands-on assistance.” All the while, the sheer heft of what he was trying to achieve with his LP was on his mind: “I was kind of awestruck,” he said. “It seemed like a huge undertaking that I would never complete.”

‘The Collapse Of Modern Culture’ is also the product of a unique confluence of circumstances. It has that rare quality, the signature of an authentic masterpiece that occurs when a work perfectly aligns with a bigger cultural moment, often incidentally, and looks it straight in the eyes without flinching. Ingram’s work was grandiose in scope — coming to the edge of the millennium, it stood with a foot in either side, composed enough to take stock, and simultaneously looking forward and back. Both hopeful and mourning for what had passed and what was yet to come, the album was written with the unfettered sincerity of a young adult on the cusp of something great, but in no great rush.

At this point of his life, Ingram was staying in bed till early afternoon, subsisting on fast food, and living on an advance. In the Wire interview, we get a portrait of a down-to earth young guy, cool and composed. “Probably money wasn’t well spent,” he said. “But hey, I spent it. I bought equipment… it got put into production as well, and some other things — you pay bills, you get clothes — and I took some odd jobs here and there too.”

Tracks like ‘D 2000’ capture this side of the album, with Dixon laying down a simple repeating groove, mixed with laughter and muffled conversations: An epiphanic snapshot of hazy summer days in the studio. At the same time, the young Ingram could see the spectre of something malignant around the corner.

“Then some of it was apocalyptic too,” Ingram continued. “It did seem things were on the brink of chaos at the time… We were still in a kind of Big Brother-ish era.” He remembers at the time reading about the changing of cultural constructs within America, leading him to bestow the LP with its rather apocalyptic name. The album’s fleeting snippets of distorted broadcasts are prophetic: Shakir’s ‘Daytime TV,’ for instance, feels like an artefact of the entertainment age, impatient overconsumption told in the flickering cacophony of packaged broadcasts. Likewise, ‘Transaction’ has a bass-driven, dubbed-out battle cry, an undercurrent of washed-up warfare.

“The album’s best moments have an air of foreboding mystery, never too dark or wavering in their intrigue; they feel like familiar echoes from the past, and at the same time, ethereal grooves from a not-too-distant urban future.”

‘The Collapse Of Modern Culture’ is also a look ahead. Ingram was interested in the technological advance and the coming age of the internet, how this would change the way humans behaved, and the decline of personal transactions — “from things like the cellphone, to the internet, to even the kinds of cars that people drive, the clothing,” he said. It’s not just the small cycles of life that were on Ingram’s mind, though — he was also concerned with “how technology changed, even down to the roles men and women play… Where you had kids with disposable income at early ages… And for a city of only one million people here, things change fast. And word changes fast, from the political climate.”

The sound of the album was, and still is, way ahead of its time. Scattered with half-time dub frequencies, ‘The Collapse Of Modern Culture’ is interested in the sounds of the future — in stripping things back to default, then listening to the process of regeneration. Ingram and Shakir provide nuanced soundscapes that would emerge across the Atlantic nearly 10 years later in London, with tracks like ‘Cultural Nimrod’ and ‘Laptop’ presaging the music released on dubstep labels like DMZ.

‘The Collapse Of Modern Culture’ does have a natural kinship with London, and Mo’ Wax, the James Lavelle–led label that eventually released it. It was one of the last releases for Mo’ Wax, and something of a swan song. For many, DJ Shadow’s ‘Endtroducing’ was the pinnacle of the label, but ‘The Collapse Of Modern Culture’ feels like something more akin to what Lavelle was reaching for in the end: A progression of something new, always evolving, painstakingly weaved with unbridled amounts of depth.

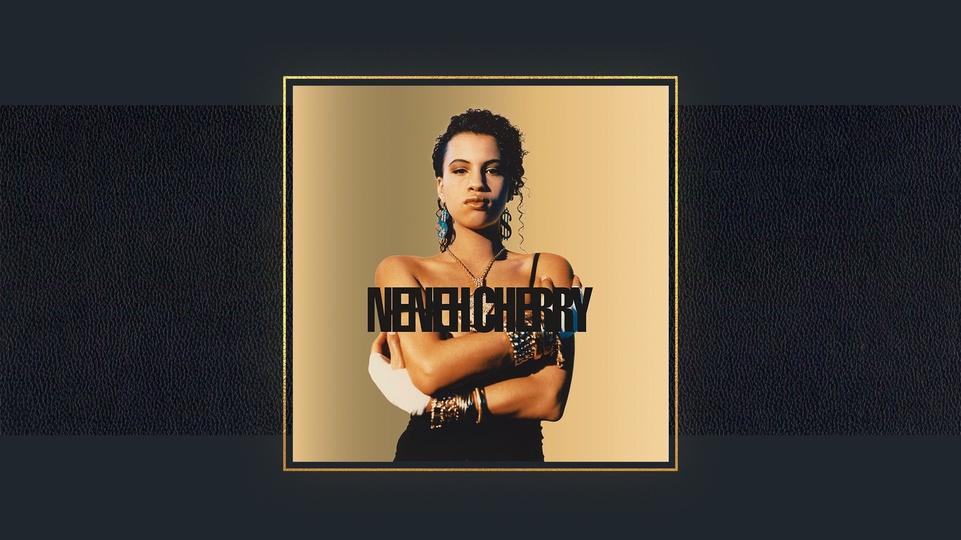

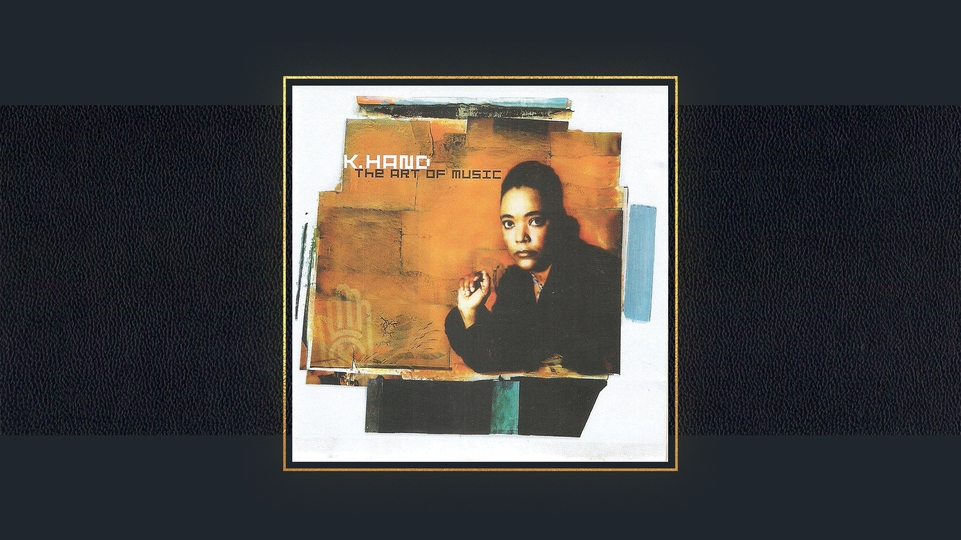

Likewise, it is the Mo’ Wax and Lavelle connection that brings us to the album’s other triumph, the pitch-perfect aesthetics of the label’s go-to designer Will Bankhead. Simple and striking, what seems like straightforward album art is a puzzle, visually echoing the album's reverberations. The inserts are haunting photographs that capture the coming age of consumerist anxiety and technological alienation, reflecting the pamphlet nature of the work.

Despite all these threads, the album’s best moments have an air of foreboding mystery, never too dark or wavering in their intrigue; they feel like familiar echoes from the past, and at the same time, ethereal grooves from a not-too-distant urban future. In cuts like ‘Nebula’, ‘Low Berth’, and ‘Peacemakers’, we hear sounds we have never heard before, and might not hear again. The British dance music magazine Muzik, at the time, described ‘The Collapse Of Modern Culture’ as “exquisitely sad but uplifting” and “moving and poignant”; The Wire said it had “the classic off-world quality and air of melancholy currently missing from most Detroit techno.” It was the starting gun for a renaissance in creativity that never really happened.

‘The Collapse Of Modern Culture’ probably won’t really ever get the wider recognition it deserves, nor was it ever looking for it. It was modest, modern, and meaningful. Continuing to reverberate, always just out of grasp, it’s like the mumbled melodies of the pedestrians on the train, or a spontaneous whistle as you walk downtown.

.jpeg.jpg?itok=cfH2MMa7)