Craig Richards: steering the ship

Craig Richards’ Houghton Festival returned earlier this month, embedding its status as one of the most important events on the UK’s electronic music calendar. But, to focus solely on Houghton when looking at Richards’ career would do him a disservice. The festival's success is the culmination of hard work that spans four decades. Here, Rob McCallum spends time with Richards around the festival to discuss Houghton's journey, the importance of having a multi-disciplinary output to maintain creative balance, and the impact of his near 20-year fabric residency on his craft as a DJ

“I’ve just arrived here, and it’s really green,” says Craig Richards, speaking about the Houghton Festival site almost two weeks before it opened to the public this year. “Can you hear me OK? The signal around here can be terr...” The line cuts him off. Richards responds by traversing Houghton Hall — the Palladian mansion in North Norfolk, the surrounding parklands of which are home to the festival’s site — to find a place to sit closer to the Wi-Fi router, dipping in and out of signal as he goes.

Anyone who has been to the festival knows that this lack of phone reception only adds to its unique charm. “I think it’s enormous,” Richards enthuses of its impact. “It’s about disengaging, and engaging with something else, which is arguably much more significant. Togetherness is a big part of being at any festival. So, surely, not having your phone can only increase that feeling. You soon get used to bumping into new people, or going to have a little walk on your own. The festival is not that big, eventually you’re going to find your friends. And along the way you might find yourself. It’s nothing but a blessing.”

The festival lights up an otherwise sleepy lake a stone’s throw from the Sandringham Estate for four days and nights every August. It started its journey back in 2017, but due to what Richards describes as a “strange, strange narrative”, this year’s event was only its fourth edition, due to a pre-pandemic cancellation caused by high winds in 2019, and two years lost to Covid. While 2022 marked Houghton’s return, this year embedded its status as one of the most important events on the UK’s electronic music calendar.

On the opening day of the festival this year, Houghton’s Instagram account shared that “the spaceship lands today”, and the meticulous 24-hour programming creates an ebb and flow of music across the weekend — an extraterrestrial electronic opera that’s heavy on the theatre, with an immaculate attention to detail.

“Houghton is for the scene and for the people and for the music.”

“We feel like Houghton is for the scene and for the people and for the music,” Richards beams. “The blueprint for how I wanted to approach it was based on my own discontent about festivals and their shortcomings. One of my grievances with them was the shortness of time. It’s just pants down. You’re on next. Curtain up. And then before you know it, you’re off again. So you have to tell the joke very quickly, which is not really my thing. It’s OK if you just get straight on with it. But it’s not particularly fulfilling for me.”

The first thing Richards and the original Houghton team did was focus on its DJ booths, ensuring each was as close to a club set up as possible, so that artists could play vinyl comfortably, on giant sound systems without any of the technical issues they’d regularly face at large-scale events nowadays. Over its subsequent editions, Houghton has developed a unique sonic and visual identity too, with a large part of that being down to the non-stop programming and properly equipped booths, which allow DJs to play extended three, four and five-hour sets as a standard. This enables artists to cover a broader range of sounds, take things deeper, and often weirder, and span different intensities within a set.

The ambience on site isn’t that of a crowd bulldozing through a four-day bender. The programming takes punters slowly up and back down over the course of each day and night. “Being up for four days is not what we’re about,” Richards agrees. “There are certainly parts of the festival which keep going, and if they close, something else is open... so if you do want to have a late night, it is perfectly possible. But, equally, it wouldn’t work in the same way if everyone was just smashed the whole time. This festival is about trying to find an honesty within all this that isn’t Ibiza, it isn’t Vegas... it’s just a bit more...” he pauses to think, “believable, really. We’re trying to be subtle, if anything. We’re trying to make it less of a fairground.”

Richards says one of the easiest things to organise for the festival has always been the artists, thanks in part to the unparalleled contact book he built up during his 18-year residency at fabric in London. Some — including Margaret Dygas, Call Super, D-Bridge, Lena Willikens, DJ Stingray 313, Calibre, Ben UFO, Saoirse, Midland, Vlada, Shanti Celeste, The Ghost, Helena Hauff and Ivan Smagghe — make returning visits, while many book the duration of Houghton off from any other commitments, staying for the weekend and playing additional ambient, dub or experimental sets, or just wandering the site and taking a rare chance to check out their contemporaries.

Speaking in an Instagram post shortly after the festival, Richards explained, “This year was undoubtedly the most significant in what has been a joyous and tempestuous seven year passage. As the appreciation and understanding of the festival rises, we in turn rise in our commitment to present the broadest spectrum of music, art and entertainment imaginable.”

This year was a massive statement of intent from Houghton after years of huge successes combined with crushing setbacks and stuttering false starts. “It was a crunching experience to have to build the whole thing and then cancel it”, Richards explains of 2019’s cancelled edition. “We’ve learned quite a lot in our quick history. But it’d be nice to think it could steady up a little bit,” he laughs.

He says it is the support of the family that owns the house and its grounds that has allowed them to navigate such a turbulent early narrative. Direct transcendents of Sir Robert Walpole, widely regarded as the de facto first Prime Minister of Great Britain, he would hold parties at the house he commissioned in the 1700s that are said to have gone on for weeks at a time. Houghton Hall has continued to push art and creativity throughout its history, and the country house’s architecture, interior design and grounds — which feature a sculpture park visited by thousands of people throughout the year — have adorned the pages of Vogue and Tatler.

“It’s a long term project. The plan is for this to keep going and going. I want it to be one of the most important festivals in the world.”

Richards is now working with a new team around him, a close knit collection of people including his girlfriend Amanda, his teenage daughter, his friend and collaborator, the DJ and producer, Bobby., Kat Simons, Ben Price, and a production crew that joined ahead of the 2022 festival. They have all pushed things forward exponentially from those still-excellent, if a little more DIY, early years.

Changes to the site this year are more minimal than in previous editions, with no new stages introduced, but some tweaks are perhaps no less significant. The biggest change is to the Warehouse. With all-new blacked out sound treated walls and full hard flooring for the first time, the space has also been kitted out with an incredible d&b audiotechnik Soundscape system, similar to the one now in use at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts. “The acts have been working with d&b to figure out how to use the equipment to its full potential,” Richards explains. The sound is sonically jaw dropping, with sounds and FX audibly travelling and coming in from 360 degrees around the room.

When Margaret Dygas drops Nina Simone’s ‘My Baby Just Cares For Me’ half way through her set on Saturday evening, the sound system feels like it has come alive, as video projections of ballet dancers are beamed onto the screen on the back wall — the only screen at the entire festival. It’s a level of pre-prepared production not usually associated with such underground dance music, but when used sparingly it works as a tonic at the heart of her set.

d&b have been in conversation with Houghton to deliver the Soundscape project — which is a giant leap forward for the Warehouse — for almost seven years, as part of a push from the company to explore immersive audio in the live space. The German speaker manufacturer deliver the sound across the site. “Festivals can sometimes start to look and feel a bit the same. They kind of become homogenised,” explains Wayne Powell, d&b audiotechnik’s global artist liaison manager. “The obsession for me is the aesthetic of [Houghton]. So much effort and energy goes into making all these very different identities... all these different spaces, and each one sonically has its own identity. It’s this playground where they want to create a club vibe in the woods, and the focus is about the experience for the audience. It's completely the other way around [to a lot of festivals].”

If Houghton is considered a spaceship by its organisers, then set deep into the darkness of the forest, it is clear that Earthling is the landing station. A looming, permanent, spaceship-like structure built into a clearing at the back of the site, it’s rigged with a giant four point d&b sound system that, when combined with its otherworldly architecture, makes it unparalleled as a rave space in the UK. This year, the DJ booth has been elevated slightly, placing the artists firmly in the centre of the crowd below the celestial structure, all under towering fern trees, illuminated in shifting saturated tones of red, green and blue.

Elsewhere, the Derren Smart stage serves as the closest thing to a main stage at Houghton alongside the Pavilion, which returns with two sunrise sessions between 5am and 8am from Midland, and Zip. “It’s a very, very special time to dance with the sun coming up, “Richards enthuses. “I don’t think there’s anywhere else in the country where you can experience it in that way.”

Pinters returns after a hugely successful first year with an incredible programme of jazz and experimental, downtempo, reggae, dub and more. Two other favourites also return in the Quarry and Terminus — the latter the only stage to run continuously for 24 hours each day, with no line-up announced. Queues snake around outside Terminus for the majority of the weekend, as ravers clamour to get a glimpse inside. “It’s fun to have a secret, isn’t it?” Richards smiles, speaking about his love for the space. “If Houghton was just [Terminus] on its own, it would still be brilliant!”

A crucial factor in transforming the parkland into an extraterrestrial rave space is the fact that the team can build permanent structures. It means they can approach building them in a very different way, and develop such strong visual identities for them. “They’re very proud of the festival and very supportive,” Richards says of the family that owns Houghton Hall. “It’s a long term project. The plan is for this to keep going and going. I want it to be one of the most important festivals in the world.”

But to focus solely on Houghton when looking at Richards’ career would do him a disservice; the success of the festival is the culmination of hard work in electronic music that spans across four decades. He is perhaps best known for his impact on the London club scene, the city he moved to for art school in 1987, after living in LA for a year when he was 19. He’d been travelling to London to go to parties at spaces like Wag Club on Wardour Street in Soho, when it was a melting pot of alternative culture, for some time. But he says everything changed shortly after, with the arrival of the Second Summer of Love.

“It was a remarkable change in culture, and in the nightclub environment. The warehouse parties suddenly started happening. And there was just so much to do,” he says about the explosion of rave culture. “It was a fantastic time for me to be at art school and to be in London. I was too young for punk, and a few different bits and pieces. This felt like it was our thing.” Pre the Criminal Justice Bill, Richards says he used to go to events in Clerkenwell, Bermondsey, and Soho, as well as Clink Street, and “kooky” warehouses in Hackney that were flown under the radar of the authorities. “No one really knew what was going on,” he laughs.

Trying to find his place after art school, he started putting on his own parties in 1993, as well as working as a promoter for existing nights, all the time honing his craft as a DJ. A few years later, as the end of the ‘90s loomed, he was presented with an opportunity that would go on to change everything, not just for himself, but for nightlife in the city he continues to call home. Two friends were opening a club in the Metropolitan Cold Stores, which had historically served as the fridge for the nearby Smithfield Meat Market in Farringdon, London. Opened in 1999, fabric established itself as the beating heart of London club culture, with Richards and Terry Francis installed as residents and musical directors.

“I still don’t know exactly what I want to be, but I certainly know what I don’t want to be. I’m quite happy with evolving and not evolving in equal measure.”

The club went on to inspire what followed in London club culture over the next decade and, personally, helped him develop a distinguished approach to DJing that sees him traverse myriad sounds of electronic music with a natural deftness. “It was a very special period,” he smiles. “And an enormous luxury. I learned a lot that I never would have from just being on tour or guesting, in terms of going across genres and flirting with different styles.”

Richards still travelled across Europe on Fridays and Sundays, but Saturdays at fabric were his playground. The two residents were given what he describes as “pretty much carte blanche” to invite who they wanted, some of whom were relative unknowns when they first played. He would spin at the venue pretty much every Saturday for nearly two decades, with a huge amount of variety, even for a resident. One week would see Richards play before the pummelling techno of Jeff Mills, while another might see him play after the Chicago house of Derrick Carter, or warm up with a dub reggae set for Rhythm & Sound.

And it informed a freedom to his approach to playing electronic music that he maintains to this very day. At Houghton, through the years, he has delivered a dizzying amount of sets. His sunrise stint on the Pavilion last year leaned heavily on the sonic tropes of psytrance, but melded into the body of twisted house and techno, while his Derren Smart set ahead of Radioactive Man this year was a precision engineered journey through varying shades of the more minimal end of electro. When Richards plays, he’ll rarely, if ever, play what you might define as a hit — he’s likely to play music that few on the dancefloor will have heard before — but still manages to keep listener’s engaged with deeply rooted tonal contrasts.

Over their time at the club, Richards and Francis played a crucial role in developing the sound of fabric, one that helped drag upwards of eight million people through its doors (and counting). It spawned a compilation series that Richards kicked off with ‘fabric 01’, which blended dubby, breaky music he described at the time as the “trippy innocence of the fabric dancefloor at 6am”. He also helped to launch the club’s in-house record label, Houndstooth. Richards announced in 2017 that he would step down from his weekly residency, partly to focus on developing Houghton into what it has become today. Though he still appears at the club regularly. Earlier this year he played a b2b with Francesco Del Garda, and another with Nicolas Lutz, and is locked in for the 24-hour 24th birthday celebration in October.

Another huge part of Richards’ career is Tyrant, the trio he formed with Sasha and Lee Burridge before taking on the fabric residency in the late ‘90s. They landed a monthly residency that ran for five years at long-missed Nottingham nightclub The Bomb, alongside a residency at The End, which later moved to fabric. The trio played and produced a sound that fits somewhere between the psychedelic, dubbier side of San Francisco deep house and breakbeat, “which is not dissimilar to a lot of stuff that’s being played nowadays,” Richards quips.

Tyrant went on to land some huge bookings, but as Sasha became busier and busier, the three became a duo, of sorts. Richards recalls one night when they were booked to play Space Ibiza and Sasha had missed a connecting flight, so couldn’t make it to the venue. “We convinced Space that we would be alright to do it on our own,” he smiles. “Most people wanted to see Sasha, really, but Lee and I played the whole night. We had a few moments to shine, created by Sasha not turning up,” he laughs. As Tyrant, they released an album and four highly acclaimed compilations — if you count 2004’s ‘fabric 15’, mixed by Richards alone. The project eventually ran its course as other commitments pulled them in different directions, but the three remain close friends through to the present day.

Richards hasn’t released any new music since 2017, when he dropped three EPs, including a pair on The Nothing Special, the label he started in 2011. Those releases were made up of twisted progressive electro (‘My Friend Is Losing His Mind’) and dubby tech-house (‘Sleeping Rough’). A third, collaborative EP with Howie B on Tuppence comprised more abstract minimal electro and featured Shaun Ryder muttering about “rubber puddles”.

Last year, The Nothing Special released Calibre’s album ‘Double Bend’, a 12” from Matthew Johnson and his Freedom Engine project, and a repress of the late Trevino AKA Marcus Intalex’s ‘Backtracking’ EP. And he says that more new material from Calibre is coming on the label soon, as well as a collaborative album Richards made on an Atari with Howie B in the mid ‘00s.

“I don’t like the idea of specialising entirely. I would not want to be sitting in a music studio all the time, nor would I want to be painting all the time, nor would I want to be DJing all the time. I need different things. For each discipline to influence and define the other.”

Each release on the label is fronted by a painting by Richards, with a visual aesthetic that has been carried through on Houghton’s artwork. At the festival, each artist is gifted with an avant-garde portrait, which is then projected onto the trees overlooking the lake. Having a creative output in the two mediums is something Richards says is crucial to him. “I don’t like the idea of specialising entirely. I would not want to be sitting in a music studio all the time, nor would I want to be painting all the time, nor would I want to be DJing all the time. I need different things,” he explains. “I want it all to sit next to each other, and in relation to each other. For each discipline to influence and define the other. I still don’t know exactly what I want to be, but I certainly know what I don’t want to be,” he smiles. “I’m quite happy with evolving and not evolving in equal measure.”

He now lives what he calls a “dual existence” between London and Dorset, and says the pandemic — although a deeply stressful period — afforded him the time to develop a body of work of music and visual art that he is now keen to put out to the wider world. “My happiest moments were when I had a painting on the go in one room, and then music on the go in the other. If you have a daily practice, then your mark making repeats itself, and you start to almost rip yourself off. It’s a beautiful thing. [And it’s the] same with the studio. You start to repeat stuff, and it becomes your own language.”

He says he is a person who struggles to finish things, and is wildly self critical. At art school, he was told that in order to finish a painting, the artist must sign it. “So I always struggled with signatures,” he explains. “I was like, ‘Oh God, it feels like the end. That means I can’t mess around with it anymore.’ In the same way, once you cut a record, it’s done.” Richards plans to DJ slightly less through winter, in order to focus on getting his bank of paintings and music to a stage where they are signed and pressed.

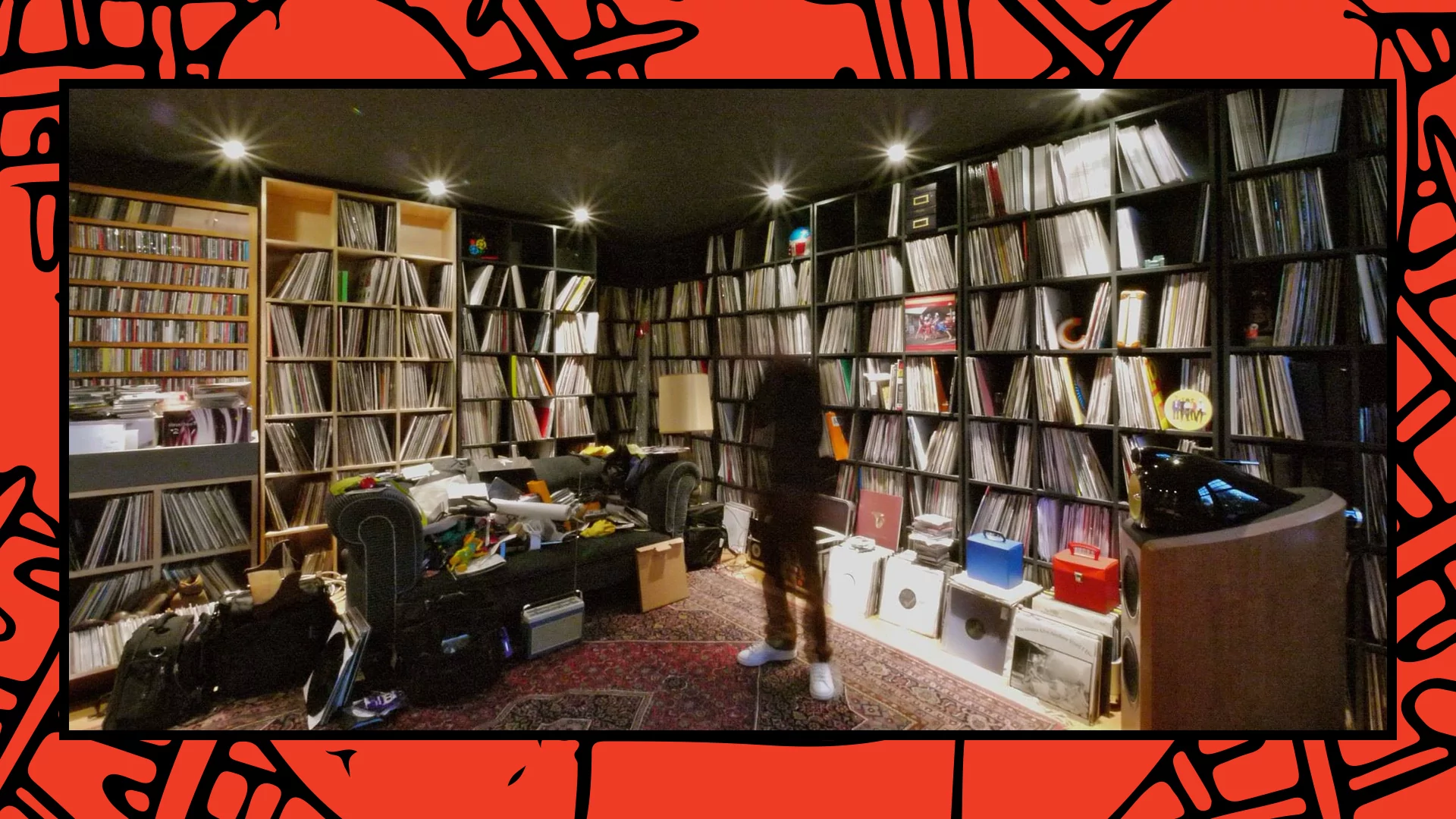

A multi-disciplinary artist with a rare, unique vision of what electronic music, and the spaces it’s played in, should be, he says it’s an innate sense of discovery that has kept him so engaged with electronic music for over 30 years. “Collecting records, and then playing them, otherwise known as DJing, is something I really adore, and love. It’s been a life of inspiration and great fun,” he concludes. “And a bad back.”

eb75.jpg)

.jpeg70ed.jpg)