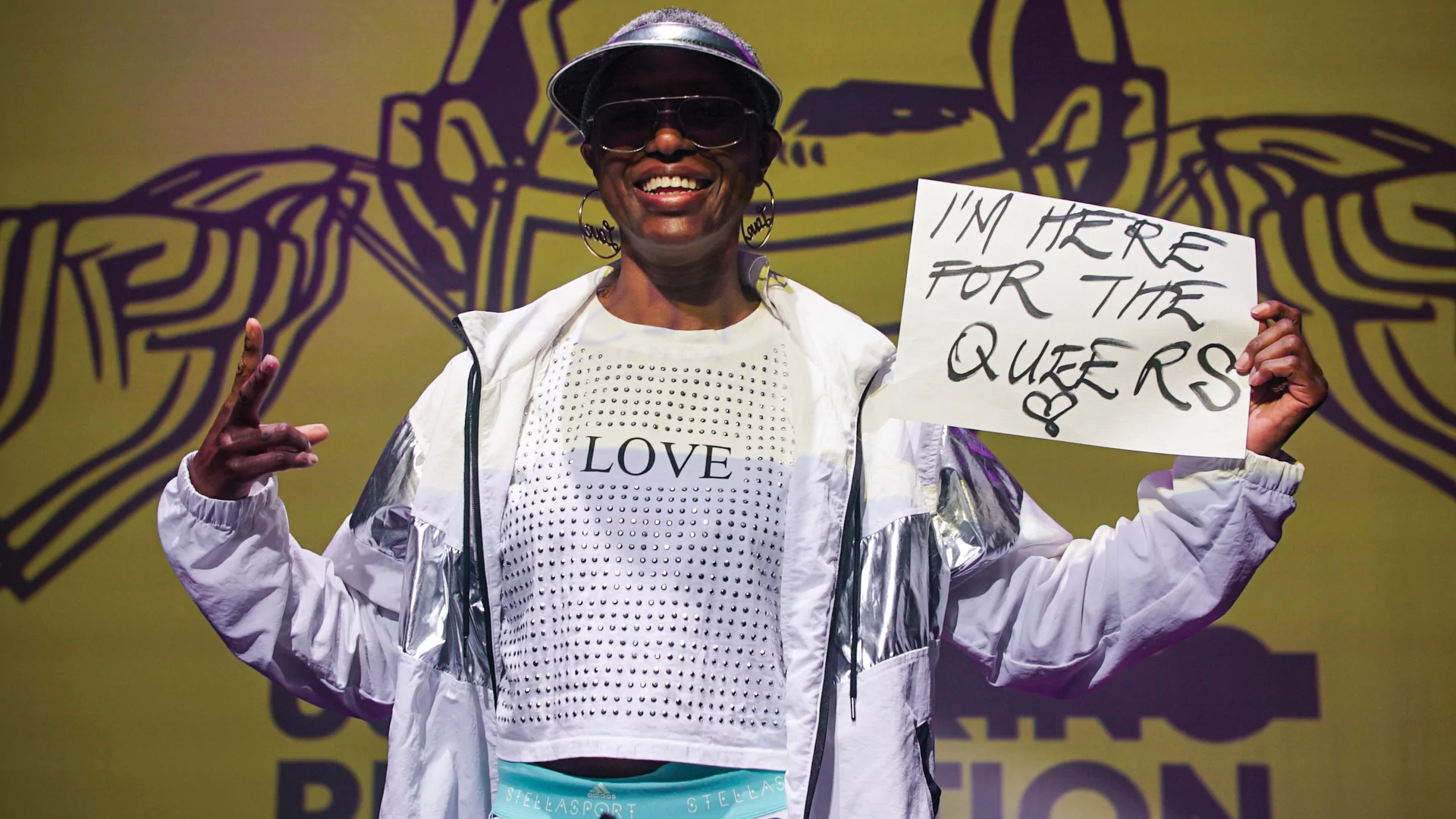

DJ Paulette is the DJ Mag Top 100 DJs 2022 Lifetime Achievement winner

Manchester-based DJ Paulette — pivotal in several of the most significant moments in European electronic music history — has won this year’s Lifetime Achievement award

DJ Paulette has been active as a DJ, radio and TV host, A&R and PR for over 30 years, in the thick of the action at crucial times in the dance scene’s development. From her early days spinning at Manchester’s pioneering LGBT+ night Flesh at the Haçienda, to helping the Roni Size & Reprazent 'New Forms' album win the Mercury Prize, she’s been a positive presence and force for good as she’s helped spread quality electronic music around the planet. She’s had a rich and varied life, which she’s currently detailing in a book that she’s writing — out next year — and it’s an honour to present her with the Lifetime Achievement award this year.

Paulette started off in the music game aged 18 as a junior reporter on Manchester’s Piccadilly Radio 261 station. A music fan, she started clubbing and buying records, and when she blagged her way into the legendary Haçienda club one night “it was a real eye-opener”.

Paulette begins telling DJ Mag how her first DJ gig came about. “Fast-forward six years of buying records and whatever and a friend of mine knew somebody who was putting on a party at the No.1, and she’d spent all the money on the promo. She didn’t have any money to pay a name DJ, and was told about somebody who had lots of records who could do it. She must’ve been so fucking desperate!” laughs Paulette.

She was offered £30 to DJ from 9PM-2AM, “which was a lot of money in 1991, and I went out and spent my grant for the term — 150 quid — on vinyl, on records, and I don’t regret spending every penny of that money, even though I was married and my husband had a face on him, because I saw it as an investment.” The party went really well, even though she didn’t really know what to do with the mixer at the time. She learned on the job with the help of sound tech Ian Bushell on the night.

“We were saying, ‘You can call us what you like, we’re gonna do this night and it’s going to be so decadent and brash and bright, with eye-popping visuals, you name it, and we’re going to reclaim ‘gay’ for ourselves’”

“That was literally my baptism of fire, because there was a club full of people,” she recalls. “It went so well that when we went to see Paul and Lucy from Ginger Productions about hosting their second room at the Haçienda for the new Flesh night they were doing, they’d been at the party and wanted to have something different in the second room. They’d heard me playing basically through my record collection — house, hip-hop, soul, rare groove, everything from Aretha Franklin and James Brown through to Kevin Saunderson and Inner City, I played right across the board.”

FLESH

Flesh started in November 1991, the first LGBT+ night at the notorious Haçienda. Manchester had the genesis of its gay village in Canal Street, but the Haç was right in the city centre. “The centre of town wasn’t that accepting of anything different, so Black people, gay people, anyone from a minority wasn’t really welcome,” Paulette says. “That’s why things involving those different groups of people were happening on the outside — in Hulme, Moss Side or wherever, that’s where all the interesting shit was happening.

“So to move the gayness of Manchester across town into the centre was, like, ‘What are they doing?’” she continues. “It was a Wednesday night, so it was midweek — you couldn’t have done it on a Saturday night, we’d have all got our heads kicked in. Politically, ‘gay anything’ wasn’t cool. You’d come off the back of Section 28, where you couldn’t discuss gayness in schools, it was almost like a book burning. The headlines in the newspapers were horrible. You had James Anderton who was the homophobic chief of police in Manchester. Even though we had equal ops within the city council, we’d come off the back of HIV/AIDS and Section 28, and doing anything gay was like a massive taboo.”

Flesh flipped the script, and became the coolest night in the city. The queer party-goers were out, proud, flamboyant and fabulous. “We shoved it in the faces of everyone, and it was the night that made the most money for the Haçienda,” Paulette says. “It showed that there was money in the gay community. The phrase ‘The Pink Pound’ came off the back of these kind of parties — Flesh, Trade, you name it. Actually showing that people wanted to go to these nights. And then straight people started to want to go. ‘Gay’ wasn’t cool in the ’90s — it is now.

“If you walked down the street even looking remotely different in 1991-2, you’d get spat on, called a fag or a poof, every fucking name,” she continues. “We were saying, ‘You can call us what you like, we’re gonna do this night and it’s going to be so decadent and brash and bright, with eye-popping visuals, you name it, and we’re going to reclaim ‘gay’ for ourselves. The strap-line for the first party was It’s Queer Up North. We set it up — you can be queer up north.”

Flesh ran for five years, although it doesn’t feature much in the music history tales about ‘Madchester’ and the Haç. “It was possibly the most diverse night that went through the Haçienda, but it just gets written out of the history books,” Paulette concurs.

She moved down to London in the mid-’90s, as most of her DJ work was pulling her south. “My divorce was going through, I’d finished my degree, I’d finished presenting the TV programme I was presenting for Granada — everything had come to a natural end,” she recalls. Paulette was offered a weekly residency at The Zap in Brighton and regular DJ slots at Heaven in London, plus other gigs nationally, and “the travelling with two record boxes was too much, the trains were really slow”.

In London, to supplement her DJing income she got a PR job at Mercury Records in 1995, after a brief spell working for Rapido TV. One subsidiary of Mercury was Talkin Loud, helmed by Gilles Peterson, which boasted a roster of Roni Size Reprazent, Nu Yorican Soul, Galliano, Nicolette, 4hero, Terry Callier, Femi Kuti and others. Meanwhile, the house offshoot label Manifesto — headed up by Eddie Gordon — had the likes of Todd Terry, Masters At Work, David Morales, Byron Stingily, Donna Summer and more on its books.

“Gilles and Eddie Gordon were constantly pressuring me, saying ‘Whose PR are you?’” Paulette says. “I was doing both to the best degree possible.” She also had trip-hop act Lamb, plus Def Jam hip-hop acts like LL Cool J and Method Man. “You name it, pretty much every Black artist going through Mercury Records was on my desk,” she says. “There weren’t enough hours in the day, and I was DJing at the same time.”

REPRAZENT

Paulette became one of the best — and busiest — PRs in operation. She took music journalists out to dinner to sell the Roni Size Reprazent project to them, as their album wasn’t able to garner any mainstream radio or TV coverage, and was rewarded when the ‘New Forms’ album was nominated for the 1997 Mercury Music Prize. Nobody gave the drum & bass opus much of a chance up against The Prodigy, the Chemical Brothers, Suede, the Spice Girls and, especially, Radiohead’s ‘OK Computer’ for the prize, but the Bristol junglists triumphed in a major measure of validity for the nascent d&b scene.

“Everything that happened for Roni Size Reprazent, and also 4hero who were nominated for the Mercury Music Prize, came off the back of the press campaign and their live gigs,” Paulette says. “It’s very rare to translate a good press campaign for some dance music singles to the Mercury Prize, it has to cross them over into the nationals and broadsheets everywhere. Obviously they had to perform live, I would never take credit for their creativity, but without that press campaign... there were so many other bands who were really great live, but they didn’t have the press.”

Paulette won a gold record for the Reprazent PR campaign, after they sold 100,000 copies of ‘New Forms’. They were also nominated for two awards at The Brits. “All of that I was heavily responsible for, but when I left Mercury Records I got a 40 quid Harvey Nicks voucher and a bottle of Freixenet,” she says.

“In Manchester I’ve found who I am, which is golden. If you don’t know who you are, if you’re really struggling to find what your identity is in music, then you’re never really going to achieve anything”

Paulette’s next day job was for two key UK house music labels — Azuli and Defected. She was Promotions and A&R Director at Azuli, and Director of Press for Defected, which she helped launch with Simon Dunmore just before the Millennium. Defected’s first year was unbelievably successful — they scored proper UK chart hits with singles like Bob Sinclar’s ‘I Feel For You’, ATFC’s ‘Bad Habit’ and Paul Johnson’s ‘Get Get Down’. After a year she left to concentrate on Azuli. “That was two years of the most ridiculous... I had to elevate it from a guerrilla independent operation and transform it into having a major label attitude to how it promoted and produced its music,” she says. “The pinnacle was A&Ring Afro Medusa ‘Pasilda’, that was my record. That came from me, the biggest selling record that Azuli ever put out — I A&R’d that.”

Latin house classic ‘Pasilda’ got passed up to Ministry after a while because Azuli couldn’t handle the demand, as it was a huge hit. “It was being licensed everywhere worldwide, we couldn’t physically cope with the production, demand and distribution,” she recalls. “Azuli was just too small. I cried the day Dave [Piccioni, Azuli boss] told me he’d handed it on to Ministry, it was just at the point that we were going to put it on Top Of The Pops. I was gutted. But you learn, don’t you.”

Just after the Millennium she mixed a comp for legendary NYC house label Nervous, and toured it worldwide via some DJ gigs for a few months. She went full-time DJing, got a show on the new Ministry of Sound radio station, and was taken on as a resident for Ministry of Sound international tours — going to Asia, South America, and many points in Europe. She’d been playing a lot in Paris, fell in love with the city, and ended up moving there in 2004 and getting a show on Radio FG.

Paulette started getting more club gigs and then a residency in Paris, played at Le Redlight with David Guetta, then did a 30,000-person street party with Étienne de Crécy and Bob Sinclar, which blew her up in the city. “I played one of the sets of my life,” she recalls, and she played every weekend in France for the next few years. After nine years in France, she moved to Ibiza for a short while before relocating back to her original home city of Manchester. “Returning to Manchester is the best decision I ever made,” she tells DJ Mag. “Is it bad vibes going back? I knew I was going back home, I was going back to fix things and do things differently.

MANCHESTER

“In Manchester I’ve found who I am, which is golden,” she continues. “If you don’t know who you are, if you’re really struggling to find what your identity is in music, then you’re never really going to achieve anything. You’re trying so many different things, and nothing is sticking. Moving back to Manchester has been amazing for me.” She name-checks the Unabombers and their associated Homobloc and Homo Electric events, Escape To Freight Island, various female promoters, Warehouse Project and others as big things that are happening in the city, as well as smaller initiatives as well.

“I’ve really come into my own here, and not just in clubs,” she says. “Reform Radio, all the little things have grown into something. People really work here to build, and are open to starting with an idea and seeing where it goes. Also, joining back with the Haçienda family has been amazing.

“People put some time into development, it’s the most inspiring place for creative people to be,” she continues. “Somewhere where people encourage you to push yourself, do it and then watch it grow. My network of friends and family here is so solid, I’m really glad I came home — and it just gets better.”

Paulette feels like she wasn’t really appreciated back home in the UK while working in France for nearly a decade — “I wasn’t just eating croissants on the Seine with a beret on me head,” she deadpans, “I was working at the top level.” She begins to talk about the book she’s now writing. Welcome To The Club: The Life & Lessons of a Black Woman DJ is due out in autumn 2023.

Paulette has been through many twists and turns in her career, all the while maintaining her position as a house DJ of quality and distinction. It’s a privilege to award her the Lifetime Achievement award this year, and she is humble in her acceptance speech that goes out during the Top 100 DJs show, just before she plays her live stream from Manchester’s iconic Albert Hall. Before we let her go, we ask: what is it she still loves about the music and the culture?

“The bass, the beat, the people, the parties... I’ve been sober since 2018, so I don’t drink or drug or smoke, so for me it really all boils down to the music and the people,” she replies. “It’s been the most amazing thing to discover... my biggest fear when I went teetotal was that I was never going to be able to DJ the same — because I was always pissed! Vodka, tequila and apple juice, you name it — I actually loved alcohol. I gave it up in order to be able to work for the rest of my life. I knew if I kept drinking and drinking, I wasn’t going to be able to sustain it at my age.” She pauses. “Music is like the blood in my veins, in a way. I couldn’t do this life without music.”

a437.jpg)