How Massive Attack’s ‘Mezzanine’ predicted a new era for British music

Released 25 years ago, Massive Attack’s third album, ‘Mezzanine’, signalled the closing of a chapter for the influential Bristol electronic group, and the beginning of a new one for British music as a whole. Spliced with jagged post-punk guitars, their final album as a trio predicted an end-of-century turn for the dark and brooding at the twilight of the rave era

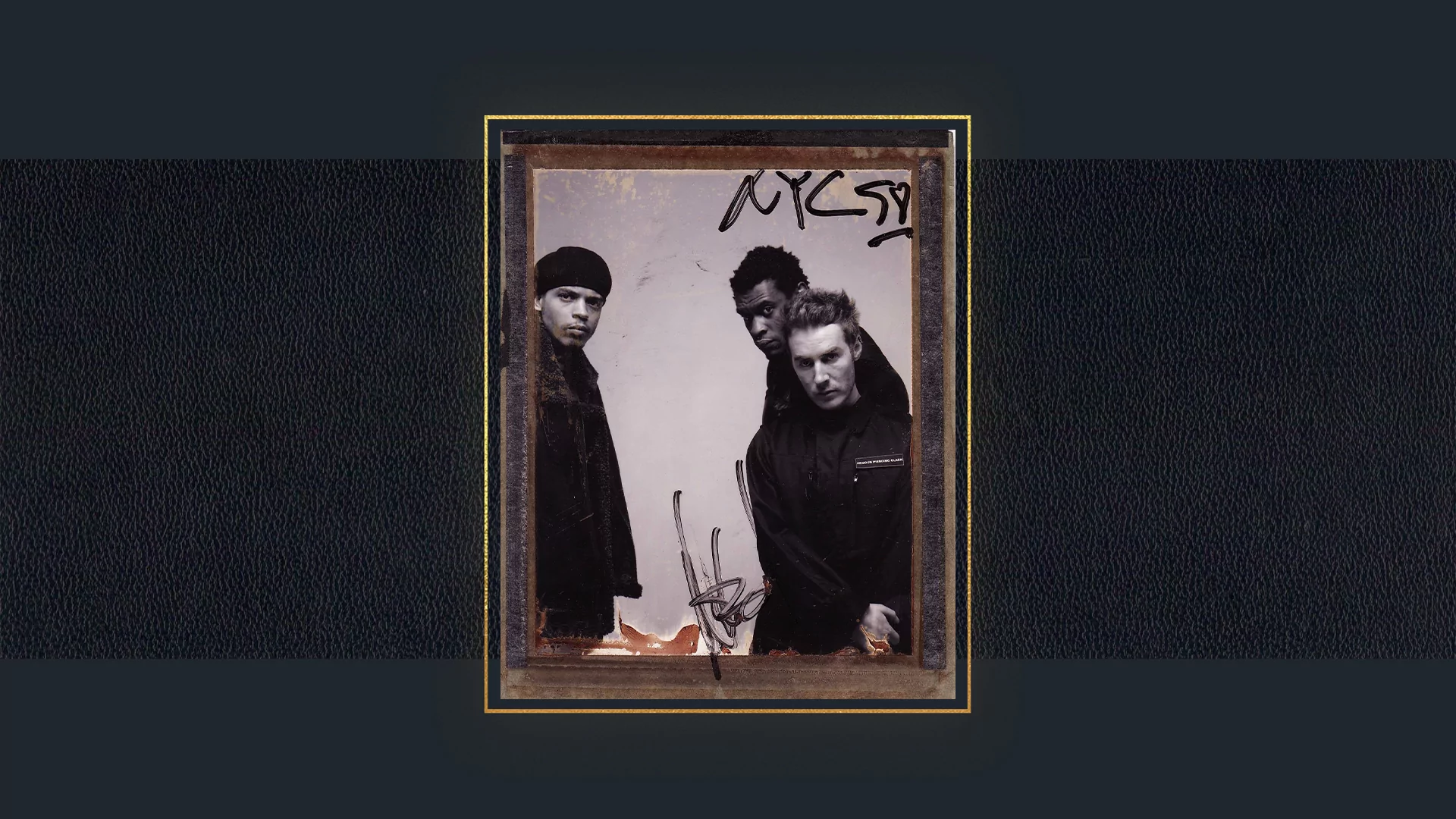

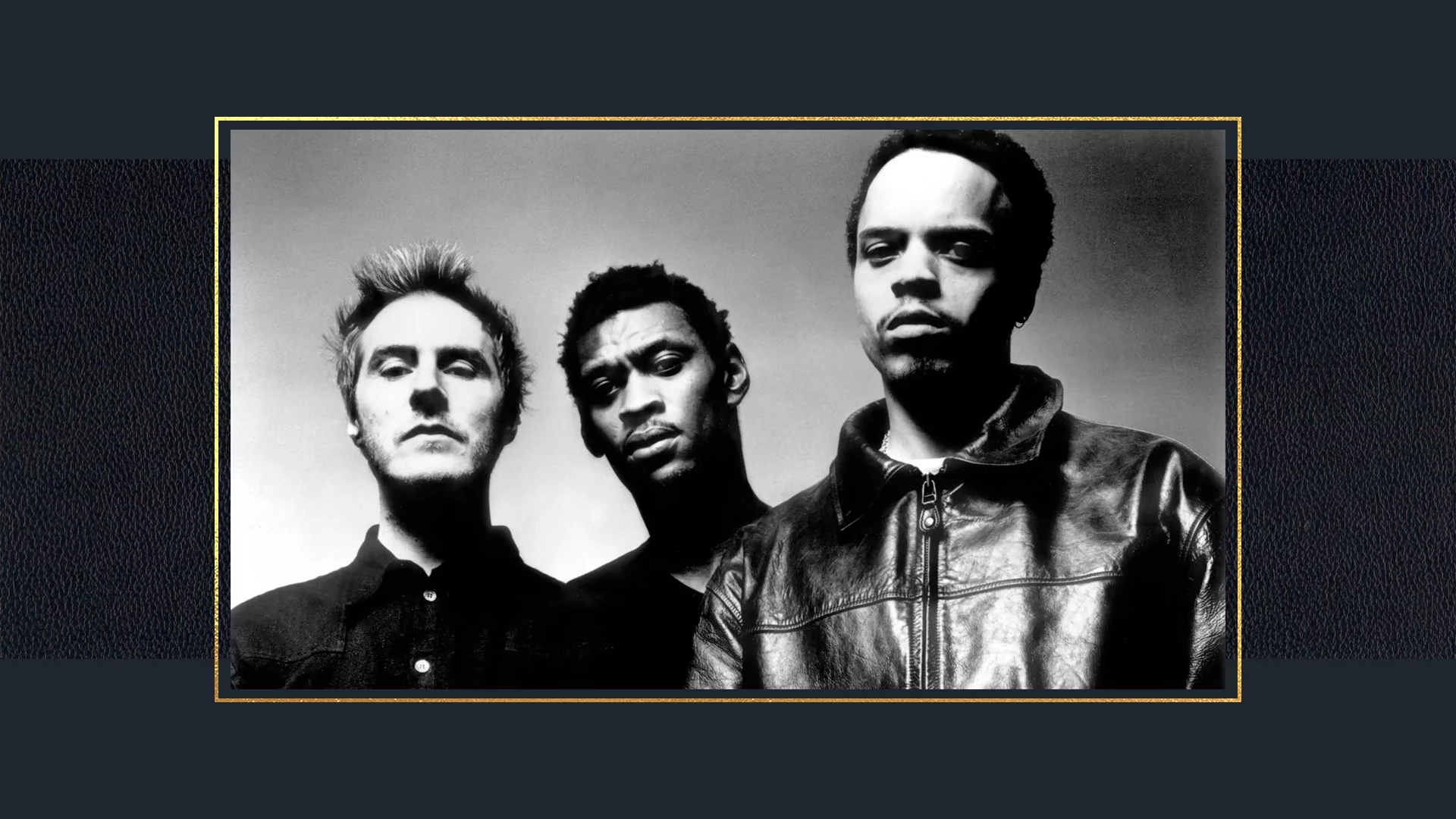

For Massive Attack, the 1990s ended on 20th April 1998, with the release of their third studio album, ‘Mezzanine’. Sure, the actual decade would go on for another 20 months, but the Massive Attack of the ‘90s — the laidback trio of hip-hop, soul and reggae enthusiasts who brought their hazy take on Bristol sound system culture to the world — came to an abrupt end with these 11 tracks: a collection of claustrophobic post-punk guitars and bad vibes that signalled a new chapter both for the band, and for British music as a whole.

‘Mezzanine’ was an album of endings. It was Massive Attack’s last LP as a trio, their last work of the ‘90s, and arguably their last really classic record. But it was also a work of re-birth; an album that predicted the post-punk revival, and helped to evolve Massive Attack from the awkward live act of the ‘90s — one stuck between the sound system culture from which they emerged and the demands of the ever bigger stages they were playing — into the festival-topping stars they’re known as today, who have influenced artists from The xx to The Weeknd. ‘Mezzanine’ might not be the band’s greatest album — who, frankly, would want to choose between their mighty opening trilogy of ‘Blue Lines’, ‘Protection’ and ‘Mezzanine’? — but it is certainly their most successful work, giving rise to their greatest hit in ‘Teardrop’, and is arguably the most influential release of their career.

If ‘Mezzanine’ sounds incredibly dark, it’s no coincidence. The album had a particularly tortured genesis, which saw the band record separately in an attempt to keep their fractured relationships at bay, the success of which can be judged by the fact that Andrew “Mushroom” Vowles left Massive Attack soon after the album’s release, leaving Robert “3D” Del Naja and Grant “Daddy G” Marshall to carry the can.

“I’ve got mixed memories of working with them,” says Sarah Jay Hawley, who contributed vocals to and co-wrote ‘Mezzanine’’s punk/dub masterpiece, ‘Dissolved Girl’. “They weren’t in a good place as a band, as Mushroom was on his way out. There was often tension and they’d argue a lot about what they wanted my voice to sound like. Mush encouraged me to belt it out like Alanis Morissette, Rob [Del Naja] wanted more understated compression and tension. Obviously, Rob got the last say. It seemed to me that him and Neil [producer Neil Davidge] were the creative alchemists on the album. Partying was high on the agenda too, as was casual sexism, but it was the ‘90s.”

At the heart of the band’s disagreements were sharp stylistic choices. Del Naja — who was then emerging as a group leader — wanted to embrace the sound of British post-punk groups like Gang of Four and Siouxsie and the Banshees (who they sampled on ‘Superpredators’, a ‘Mezzanine’ session song that was released on the 1997 film soundtrack for The Jackal). Marshall agreed, having grown tired of Massive Attack’s rather smooth reputation; but Vowles thought differently, allegedly shouting “Are we a fucking punk band now?” during one of the album’s recording sessions.

Whether the story is true or not, this is an illuminating question — and one that doesn’t have a clear answer. On the one hand, there are numerous punk elements to the ‘Mezzanine’ sound. While ‘Blue Lines’ in particular was based on samples — it was notably the work of a group that had recently emerged from Bristol sound system, The Wild Bunch — ‘Mezzanine’ grew from live recordings, and raucous ones at that.

Guitarist Angelo Bruschini had a rock background (in Bristol band, The Blue Aeroplanes) and added intense, distorted lines to songs like ‘Angel’ and ‘Risingson’, the hard-hitting set that opened the album in a haze of paranoia and noise, much to the surprise of many hardcore Massive Attack fans. The influence of post-punk, meanwhile, could be heard in the album’s staccato guitar riffs and simple, dramatic basslines, which brought to mind PiL, Magazine and even The Cure, whose ‘10:15 Saturday Night’ Massive Attack sampled on ‘Man Next Door’.

But ‘Mezzanine’ never threatened to be a straight-forward rock album. Yes, the 11 songs were based on live band recordings, but Massive Attack took these, cut them up and made them into loops, using rock instrumentation as a building block for something altogether stranger and darker, with a DJ’s eye for sonic manipulation. This gave the album a curiously off feel: ‘Mezzanine’ is like very precise rock music, engineered by hip-hop studio rats, that stands apart from the fuzzy live snarl of your typical garage band; or, perhaps, it’s hip-hop made in a world without disco and funk.

Massive Attack were clever enough to keep some of their reggae and hip-hop influences on ‘Mezzanine’, even as punk came beckoning. Legendary roots reggae singer (and habitual Massive Attack collaborator) Horace Andy lends his yearning vocal lilt to three songs: ‘Angel’, which is based on his own 1973 song ‘You Are My Angel’, the John Holt cover ‘Man Next Door’, and the gorgeously languid, jazz-inflected album closer ‘(Exchange)’. The album’s basslines, meanwhile, have the low-depth charge of dub. (Dub, incidentally, was also a big influence on post-punk music, with PiL bass player Jah Wobble being a massive fan.)

Hip-hop remained in the mix, too, with the band using classic breakbeats — notably, Led Zeppelin’s ‘When The Levee Breaks’ on ‘Man Next Door’ and the Incredible Bongo Band’s ‘Last Bongo in Belgium’ on ‘Angel’ — alongside drum machines and their own in-studio recordings to give a bombastic rhythmical power to their songs. 3D and Daddy G also contributed vocals to the album in their typically abstracted and rather enigmatic rap style. On ‘Risingson’, you can almost imagine the two vocalists passing the mic back and forth, their eyes crossing across the studio floor, creating what feels like a rare moment of spontaneous warmth within the album’s crooked studio mix.

What’s more, Massive Attack were still able to cook up a moment of classic pop sublimation in ‘Teardrop’, where the beatific vocal of former Cocteau Twin Elizabeth Fraser meets a harpsichord riff and sparse hip-hop beat in a moment of ecstatic perfection. ‘Teardrop’ has gone on to be Massive Attack’s best-known song by some distance, approaching a quarter of a billion plays on Spotify and being covered by everyone from Simple Minds to José González.

On paper, perhaps, this punk / dub / hip-hop / pop / Turkish Çiftetelli (on ‘Inertia Creeps’) fusion sounds like an improbable mixture. But it is to Massive Attack’s eternal credit that they made it work, sending their own career spiralling off into new paths and inspiring a wave of artists. In April 1998, when ‘Mezzanine’ was released, the record initially sounded like a slap in the face for a generation of music fans in the UK who were still holding on, just about, to the ‘90s dream of rave, New Labour and the collapse of the Berlin Wall.

But rave was on its way out of fashion, with guitars making a comeback in 2001 as bands like The Strokes and the White Stripes made mainstream rock music sound new again. Three years later, when UK indie acts Franz Ferdinand and Bloc Party released their debut albums, the angular guitars and sparse musical production of post-punk, which Massive Attack had borrowed on ‘Mezzanine’, were the driving force in rock, while also providing an inspiration to the likes of LCD Soundsystem, The Rapture and the other DFA bands in the U.S..

Meanwhile, as global politics took a nasty turn, with ‘90s optimism battered by 9/11, the War in Afghanistan and a vicious global recession, ’Mezzanine’’s brooding, minimal sound seemed to make even more twisted sense, its influence growing even as its follow up ‘100th Window’ sunk without trace. The xx, whose doleful debut album was released in 2009, were almost certainly listening, as was The Weeknd, who sampled Siouxsie and The Banshees and Cocteau Twins on his debut mixtape, 2011’s ‘House of Balloons’.

Thom Yorke’s solo work, and in particular his debut ‘The Eraser’, with its dark, minimal beats, also has the distinct air of ‘Mezzanine’ to it; Edinburgh trio Young Fathers sound like a band who took ‘Mezzanine’’s abrasive, experimental spirit as their founding text (and later collaborated with Massive Attack on the 2016 EP ‘Ritual Spirit’); FKA Twigs’ sombre, avant-garde sound has clear roots in ‘Mezzanine’’s shadow-y earth.

‘Mezzanine’ was the second time in 10 years that Massive Attack had re-written pop’s rule book, after the stellar success of ‘Blue Lines’ had helped to give birth to the downtempo form of hip-hop that — for better or worse — came to be known as trip-hop. That Massive Attack managed to do this twice, over the course of just three albums, is a remarkable achievement, the sign of a group that trusted in their ability to reinvent themselves along their own lines.

For Massive Attack themselves, ‘Mezzanine’ was arguably their most important album, for the way it set up phase two of their career. In 2023, Massive Attack haven’t released a new album in more than a decade, with only a handful of new tracks coming out in the intervening years. And yet — at least until 2022, when illness forced them to cancel a run of European dates — they’ve remained a vital live pull, capable of headlining festivals and arenas around the globe.

And this, in no small part, is thanks to ‘Mezzanine’, whose live-instrumentation-based sound enabled the band to transform from an uncouth Ugly Duckling of live performances — their Glastonbury 1997 performance was seen as distinctly underwhelming — into their current incarnation as a band of acute live force. ‘Mezzanine’ songs ‘Angel’, ‘Risingson’ and ‘Inertia Creeps’ dominate their live sets, and in 2019 they toured Europe and the US to celebrate the album’s 21st birthday.

No wonder new generations are paying attention. “My daughter sent me a video from a party the other day, ‘Dissolved Girl’ was playing, she’s 22,” says Hawley. “So it seems safe to say ‘Mezzanine’ has aged well. It’s become one of those cool seminal records. In the ‘80s I’d listen to Hendrix and Neneh Cherry, Steel Pulse and Stevie Nicks and be stunned by the quality and integrity of their albums. ‘Mezzanine’ is one of those records for my kids’ generation.”

.jpeg4cc0.jpg)