Hyperdub: Another future is possible

Kode9’s Hyperdub has been a critical force in shaping a more diverse electronic scene, both sonically and socially. Having weathered the loss of Chicago footworker DJ Rashad and British dub poet The Spaceape, the label found a new outlet for their borderless world building with cutting-edge London party Ø. DJ Mag speaks to the key players that make up the 21st century's most futuristic underground unit

Fifteen might be the anniversary that it is currently celebrating, but the most important number in Hyperdub land is zero. Stylised as Ø but pronounced as the number, the event, run out of Corsica Studios in the Elephant & Castle area of South-East London, has been a vital part of London’s clubbing landscape in the late 2010s. As the spaces that belong to immigrant communities in Elephant & Castle are systematically stripped away, replaced by faceless new builds and upscaled noise (read: societal) controls, Ø functions as an isolated enclave — one little hub that remains and resists.

Zero also happens to be label founder Steve Goodman’s current level of music-making productivity. As Goodman is best known as Kode9, one of the two artists on Hyperdub who reliably shift units, this presents a bit of a problem.

We visit his South London flat on an overcast July day. Even with pallid skies, the blinds are drawn and the studio occupying the top floor has a pointed atmosphere of seclusion. His home is like a walk-in version of a Hyperdub record sleeve: the walls are painted camo green, glossy translucent panels are strewn about, and an array of “misfortune cats” line the book and record shelves. These are a bastardisation of the label’s signature lucky Maneki-neko, with three eyes and a paw used for knifing itself in the head rather than waving.

Goodman is sat at his computer, flanked by a Juno 60, Yamaha DX7 and Moog Voyager that aren’t seeing much usage.

“I hadn't noticed that I hadn't been finishing music,” he laments. “I've just been too busy. And it's only been this year when I've thought, ‘What am I doing!?’ I gave up teaching to make music, and then I get distracted very easily.” He hits a vape filled with lemon haze CBD oil, then rubs his forehead and laughs. “You can only have a certain amount of ‘labour of loves’ before you go insane.”

The teaching he refers to was a position he held throughout Hyperdub’s first 10 or so years, as a lecturer at the University Of East London. Much of nomenclature attached to 21st century underground bass music — sonic warfare, audio virology, music liberation technology — has his fingerprints all over it. But across various creative outlets, Goodman never weaponises his intelligence. Hyperdub is such a welcome presence in electronic music because it exists on many simultaneous planes of depth. You can nod your head to the weird sounds it puts out, or you can take a trip down endless wormholes of associated theory.

In person, Goodman is warm, witty and endearingly idiosyncratic. He doesn’t enjoy the colour blue — after some probing, he puts it down to “fucking hating Rangers” when growing up in Glasgow — but is cheerily content listening to warp-speed club bangers while writing conceptual pieces on a post-independence Scotland evacuating to a space colony, as England is subsumed by rising tides, fascists with nukes, or both.

If Goodman’s flat represents the Futurama-style gigantic brain, Hyperdub’s office is the nerve centre of the operation. The days when label manager Marcus Scott had to venture to Goodman's place for business ended in 2013, with Hyperdub HQ now situated in the 11th lot of an SE15 yard also populated with organic bakeries and cargo dispatch units. Techno tourists occasionally rock up, including, memorably, a gaggle of blasted Italians. Perhaps expecting Four Tet clambering into a fleshy Burial exoskeleton, they were instead greeted by what almost any independent label looks like in this day and age: an annotated white board, some framed ephemera, deadstock piled up on the floor, and confused faces.

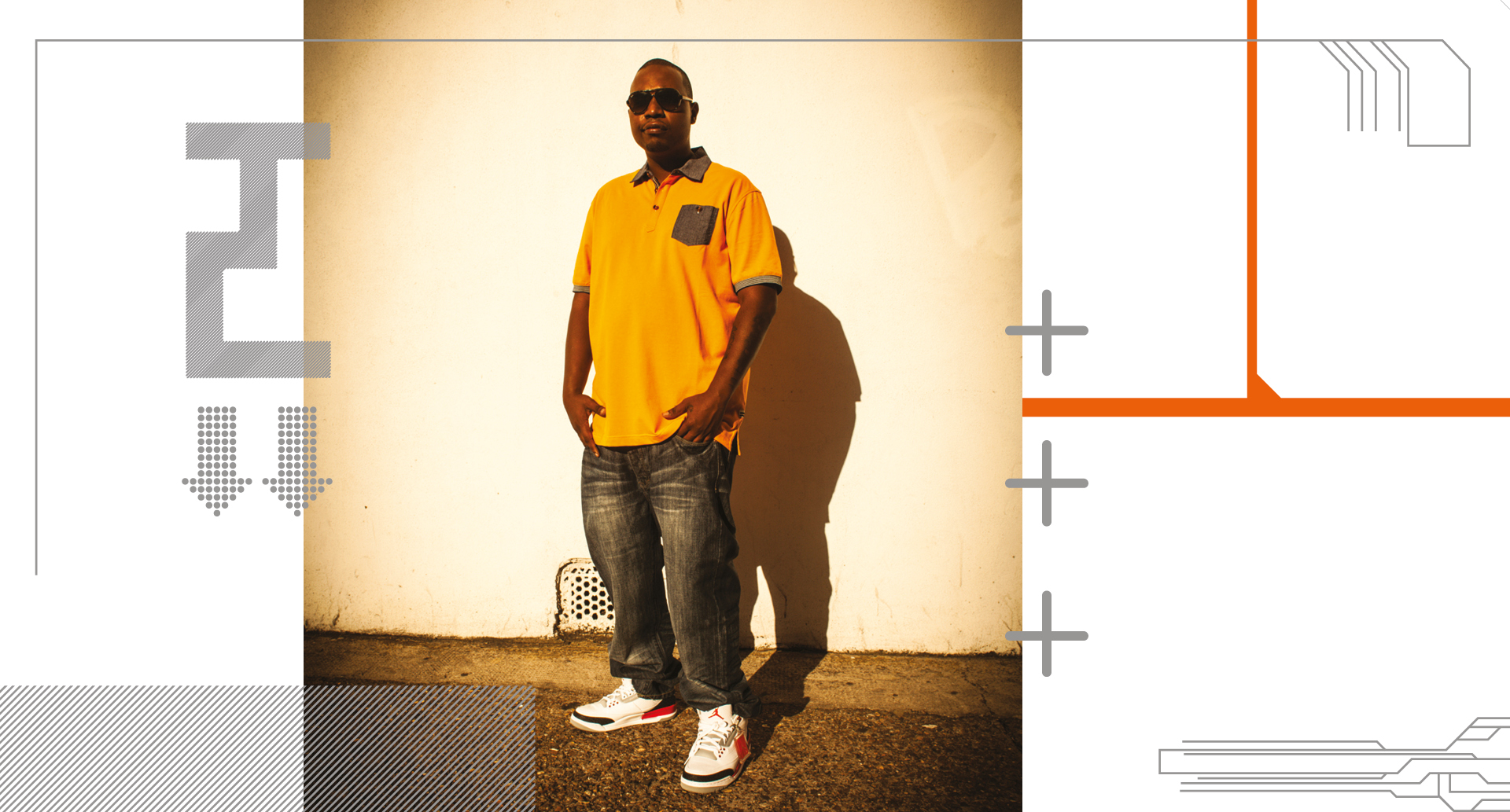

Scott, an electronic music lifer who is 44 years old but looks about 15 years younger, diligently guides much of Hyperdub’s internal affairs, co-ordinates the label, provides a bridge between the various departments, and generally wrestles order from chaos.

“I ain’t got time to try and be famous,” he says over text — which seems accurate. He works alongside Bill Dolan (distribution), Kris Jones (publishing) and Shannen SP. The latter does a bit of everything: co-curation of Ø, A&R, and providing a fresh front through DJ sets and an NTS Radio show. Goodman no longer has time for broadcasting. Time, in general, is at a premium.

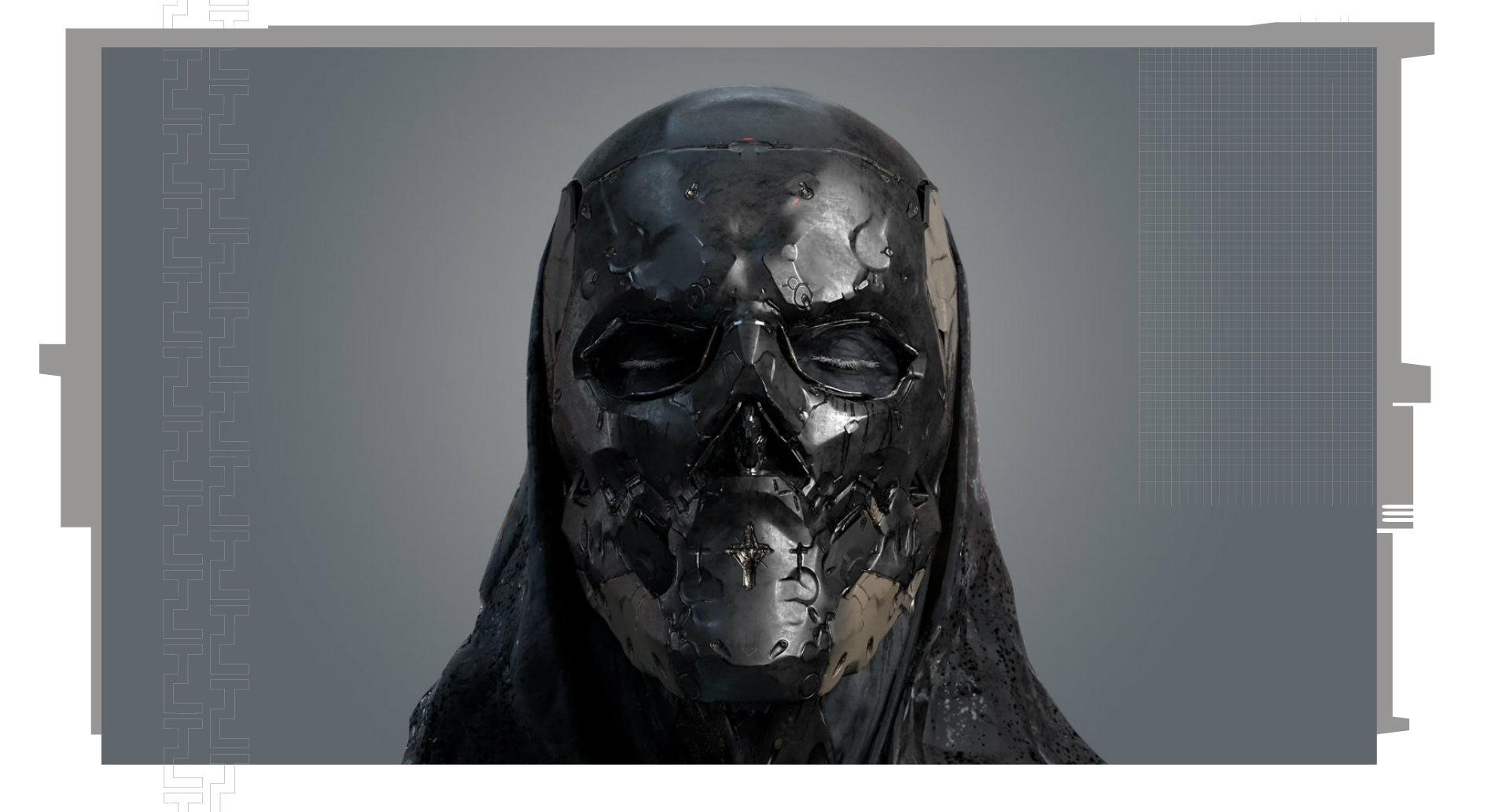

Since last November’s joint Kode9 & Burial ‘FABRICLIVE 100’ — announced with a photo of Goodman in a mask and Burial foregrounded, which sent infatuated fans around the world into paroxysms of frothing rapture — there have been a further 11 records released with more due to be announced imminently. Our meetings were sandwiched between a full label contingent playing at Glastonbury, one Berghain takeover, and two Øs. The London shows variously featured a VR headset installation, NAAFI affiliate Lechuga Zafiro, Bristol’s percussive wizard Batu, Kenyan breakout star Slikback, and Bala Bala Boyz, a six-piece group reflecting the Congolese diaspora in London. Just a few weeks before they bounded around Room 2 of Corsica Studios, spitting in their selfstyled English and Lingala (Linglish) over grime classics by Danny Weed, a film entitled Demystification Committee had screened, tracing the movement of wealth up the social ladder behind the smokescreen of Brexit. To understand the need for this dizzying array of activity, it’s important to look at the void it fills.

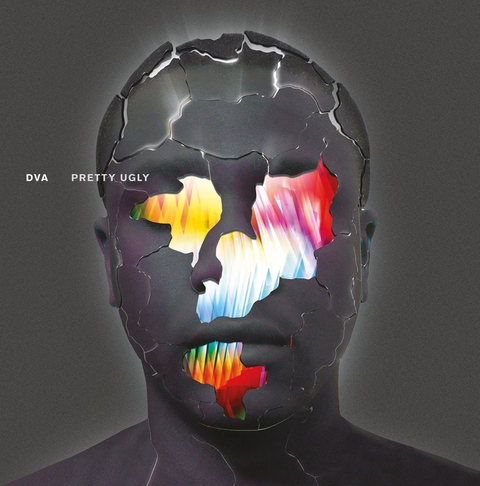

For 15 years, Hyperdub has remained durable, forward-thinking and widely celebrated, with generationally great music pouring forth. Yet it is not necessarily a ‘buy on sight’ kind of label. You have to have broad tastes in order to love it all, and the label is not impervious to the kind of dull, intra-catalogue critiques from fans about which year of releases was stronger or weaker than another. There are shared attributes and ambitions among the diverse coalition of artists that make up the roster: big dreamers, captivated by cluttered skylines and science fiction, with one eye trained on the future and a clear idea of how to get there. But musically, the connections have long been a head-scratcher. How could the shock therapy of The Bug and Flowdan’s ‘Skeng’ co-exist with Darkstar’s slo-mo synthpop? Once you’ve signed them, how do you actually go about marketing Mark Pritchard and Morgan Zarate?

If you study the label’s topography, its core artists have traditionally been arranged into loose cliques. You have the Latin freestyle faction (Jessy Lanza, Ikonika), the beats-as-war camp (Fatima al Qadiri, Kode9), and those who find a home somewhere between UK funky, grime, experimental and technoid drum tracks (Scratcha DVA, Fhloston Paradigm). Though the bright trills of chiptune and the slick squeal of Bristol’s “purple” sound have long since run their course, tunefulness and colour linger. A mix of what Ikonika calls “playful, romantic, cheeky little melodic bits, coupled with 20Hz of sub bass” formed the frequency palette that marked Hyperdub out. Light scythes through the dark. The chatter surrounding Hyperdub can be gloomy, but the music rarely is. This comes back in part to Goodman, who animatedly zigzags in and out of conversation to tell us about his love of 'Seven Steps Behind', the recent album by new signing Mana ("A very special experimental record, one of my favourites of the year") with the same enthusiasm he extends to longstanding team member Cooly G ("hands down my favourite house DJ, still").

A mixed bag of experiences working at Rephlex and Warp forged Scott’s approach to business ethics. Hyperdub signings have always been granted freedom to break off and return as they pleased. “A lot of labels operate like page turners; next, next, next,” says Lee Gamble, who joined in 2017 but has been an admirer since the start. Hyperdub, though, prizes the individual, recognising that the component parts form something stronger. It just doesn’t have the metaphorical or literal time for dickheads; only a few releases have ever had a (faint) black mark put next to their name. This duty of care doesn’t go unnoticed, says Gamble.

“They are fundamentally a good bunch. To allow their artists to breathe, develop and establish trust… it helps glue everything together. If someone gives you a good platform to do that, why move?” This is a sentiment Scratcha DVA, Okzharp, Ikonika, DJ Haram and DJ Taye all share.

For a period, though, the label did give off a selective and shadowy vibe. Quarta330 was press-averse, Goodman would cover his facial features with trapper hats and blocky sunglasses, or a cardboard box on occasion — and of course, there’s Burial. Following a Mercury Prize nomination in 2008, his identity became such a hot-button issue that The Sun newspaper broke from its diet of blaming sporting disasters on victims and hacking phones to hound a low-key dubstep producer instead. With usual journalistic rigour, the tabloid eventually concluded that Burial was Fatboy Slim. By Goodman’s own admission, a period of drift set in around this time. Once 2009’s ‘5: Five Years Of Hyperdub’ roundup was out, the next stages had not yet been locked in.

Then came DJ Rashad. Planet Mu brought footwork to the wider world through the expository ‘Bangs & Works’ compilations in 2010, but the scene didn’t blow up instantly. Even in its hometown of Chicago, it lagged in popularity behind trap and drill. Without a sudden fame surge to knock him off course, Rashad sharpened his craft and overtook his cohorts on the outside lane. He would churn out material at a prodigious rate and seemed able to fashion a tune out of anything: cascading tears from viral TV clips, twisting the blubbering syllables into wholly new words, like Detroit’s MPC wizard J Dilla used to; making Gil Scott-Heron and Stevie Wonder’s vocals sound like they never had before.

In late 2012, a tranche of stockpiled songs made their way to Goodman, who was aware of Rashad and Spinn, but was not in regular contact with them. He was instantly hooked. He floored the end of his ‘Rinse:22’ commercial mix with eight unreleased Rashad tracks across the final 10. Up and down the UK, rough mixdowns of future hits would ricochet out of Funktion-One speaker stacks to delirious effect. This new style was in the same tempo as Goodman’s beloved jungle, but had an entirely different sonic vocabulary. With Rashad leading the line, 2013 was a banner year for Hyperdub: his album, ‘Double Cup’, was a smash, and ‘Let It Go’, from the ‘Rollin’’ EP, was cited as footwork’s equivalent to ‘Strings Of Life’ — an uplifting, emotional and devastatingly powerful sucker-punch.

In a very short amount of time, Rashad’s name now stood for a sound, a city, a movement. His playful demeanour added some necessary levity, too, helping shatter the lazy association to moody dubstep that still lingered. This was it: Hyperdub had its lodestar.

On the evening of Saturday 26 April 2014, Goodman was in a Swiss train station when news filtered through that Rashad had overdosed — fatally.

“Everyone at the label is devastated by his passing and wish to send our sincere condolences to all his friends and family in Chicago, the Teklife crew and anyone anywhere who was graced by his presence and uplifted by his music,” read a Hyperdub statement sent out the following Monday. Goodman’s personal input carried on: “I’ll never forget singing a duet with him in a karaoke bar in Tokyo”.

Less than six months later, Goodman’s phone buzzed again, this time while he was in a Brazilian hotel. His recording partner The Spaceape had lost his battle with cancer. Having deliberated over going on tour in fear of that exact scenario, Goodman was now 5,000 miles away, tasked with organising a non-religious funeral for a man who was as close to him as family.

“I did have to retreat after that,” Goodman tells us. “I was trying to work out whether to go out on New Year’s Eve, and I was like, ‘You know what, fuck this. I’m going to stay in and start an album’.” The resultant ‘Nothing’ was pockmarked by grief, long pauses marking the places his MC should have filled.

Without The Spaceape’s gravelly baritone echoing down the hallways of Kode9 productions, Goodman hoisted his desire for a creative partner out of the studio. He designed the Nøtel with multimedia artist Lawrence Lek, a simulation of an abandoned luxury hotel that was initially explored through the lens of a drone, and eventually made tangible as a physical installation in The Hague, London’s Docklands, and as part of Ø. On screen, the space was devoid of all life, save for two holograms: Rashad and The Spaceape. “If they go in there,” Goodman thought, “they're going to be there forever — so at least I know where they are.”

From this “flurry of nothings” came Ground Ø — though the touchpaper was in fact lit by the most recent arrival to the label’s inner circle. Shannen SP, two decades Goodman and Scott’s junior, was connected to them by long-term visual designer Optigram, assisting on his NTS Radio show before earning her own. She soon began splitting her time between Hyperdub and her studies at Goldsmiths. Brimming with ideas, she was determined to get a regular club-night going, even though Goodman initially resisted. A realisation soon dawned on him.

“You can travel the world playing,” he says, “but if there's nothing going on when you come back, it's a bit pointless.” Same too for anything that tries to retrofit a mode of nostalgic partying to a city and climate no longer equipped for it.

Instead of throwing the odd label party, establishing fresh chemistry between musicians and multi-disciplinary artists was what excited Hyperdub, and doing so outside of the cutthroat competitiveness of the weekend. Crucially, it could function as a loss leader.

“We can be more experimental and take more risks with our line-ups,” Shannen says. “I feel as though we don’t have the same panics as some other people running nights. It’s nice to be able to play with the people who are inspiring you, to book people because you rate their work.” If Arca or Dillinja are available to swing by, that’s great, but it’s by no means an imperative. Headliners are deessentialised. The font on the flyer is consistent from top to bottom, as is the pay structure. Everyone is on an equal footing, a key facet of Ø’s M.O.

Musically, Ø is where numerous leylines of recent club movements converge, from jungle’s resurgence to the nonlinear rhythms of Central and South America, East and South Africa, and beyond. The booking policy is as much about showcasing Hyperdub artists and white-hot performers in the label’s general proximity as it is about “ethnofuturism,” says Shannen. “At first we were looking at Afro-futurist stuff, and it's kind of branching out from that now. My whole taste in music is linked with that. I'm interested in interesting rhythmic patterns, but I'm also interested in diasporic and culturally mutated sounds.”

As well as providing a space for talents passing through or coming up in London, Ø keeps Hyperdub’s existing roster fuelled with new energy, which fosters a sense of anticipation for regular attendees. Goodman holds court all night long every January, and fills closing slots intermittently, too. Scratcha and Shannen have appeared four times. Regulars like Cooly G, DJ Taye, DJ Haram and Laurel Halo, two apiece. Everyone we asked buzzed enthusiastically about just how receptive the audience at Ø had been — Fauzia, Taye, Haram — and how good it was to play with like-minded artists in front of dialled-in crowds. Some don’t dance at all. “Many people,” Gamble has noted, “go there to simply look at the installations. Then they go home and have a piece of toast, rather than gub pills or whatever.”

One night in particular illustrated the synergy that takes place under Corsica Studios’ roof. The opposing forces of woozy singer-songwriter Tirzah and chaotic rap whirlwind Ize were both booked to play live in Room 2, with the enormously influential garage producer El-B on the decks. An extra layer of eyeball-rattling subs were activated, and a claggy green fog heightened the sense of disorientation, making it hard to discern where the thicket of ceiling camo material ended, and the fingers stretching out to it began. Yet the most compelling action came in Room 1, through a piece entitled Strange Fruit, performed by Venus Ex Machina.

“It was some old school performance art, a test of her endurance physically and mentally,” Shannen says. “She was reading a series of GPS coordinates of stop and searches on black youths — with no further action taken — in London during the space of a month. She read for four hours and got really tired; I asked her to stop because she was becoming drowsy, but she continued. No one could have predicted the strain it would have had on her, and then the piece took on a whole new meaning. The kind of exhaustion and harmful effects on the community as a whole that comes from dealing with institutionalised racism. Obviously, a lot of people had come to see Tirzah. Some of them may not have exposed themselves to these topics before. It was powerful.”

For all the evocative landscapes painted across the classics of the Hyperdub canon, Ø is the label’s most important act of world-building to date. On a theoretical level, it is reflective of Goodman’s personal politics — a vision of the possibilities that would come freely in an open-borders Britain, rather than a few resilient holdouts protecting cultural commingling from encroaching threats.

In a tangible sense, it turns back the clock on a certain type of special party, including FWD>>, that Londoners so frequently lament the loss of. These were places where keen-eared young producers like Okzharp and Ikonika once lurked, absorbing frequencies. But for Shannen, what is most vital is a space for expression.

“When Fatima Al Qadiri played and the room was filled with girls and femmes of Middle Eastern descent,” this was beautiful to her. She lists the “black Goths” drawn out by Nkisi and Klein, the “young queer Londoners” in attendance for Doon Kanda, Arca and Angel-Ho as “affirming moments”.

This is still London in 2019. Corsica Studios is not a perfectly ring-fenced environment. But dramatically reducing the kind of leering, territorial, sometimes physically disruptive shit that artists of colour can draw when performing is essential work.

“When a lot of black people and people of colour are comfortable enough to come into the night and spend the evening there,” Shannen says, “when it feels inclusive to people that maybe wouldn’t go to a night that wasn’t specifically [listed as] queer or POC, that's kind of when I feel happiest; I feel like I have done my job.”

Through the promise of more dazzling footwork from DJs Taye, Spinn and the rest of Teklife, and more thoughtful poetry aired at Ø, echoes of DJ Rashad and The Spaceape’s messages continue onward — but, sadly, only echoes. If the theory of hauntology has taught us anything, it is that the future we wish for may never materialise. Better to construct the present you want while you have the agency to do so. When fretting about his writer’s block, Goodman told us that while “you can’t rush” the creative process, “you can kind of engineer the circumstances to make it more likely that something will click”. Ø is a testament to that. It should fuel a new generation of Hyperdub artists, ensuring that the next 15 years are as fruitful as the last.